There are many things that we take for granted in this world, and one of them is undoubtedly the ability to clean up your files – imagine a world where you can’t just throw all those disk space hungry things that you no longer find useful. Though that might sound impossible, turns out some people have encountered a particularly interesting bug, that resulted in silent sweeping the Trash under the rug instead of emptying it in Nautilus. Since I was blessed to run into that issue myself, I decided to fix it and shed some light on the fun.

|

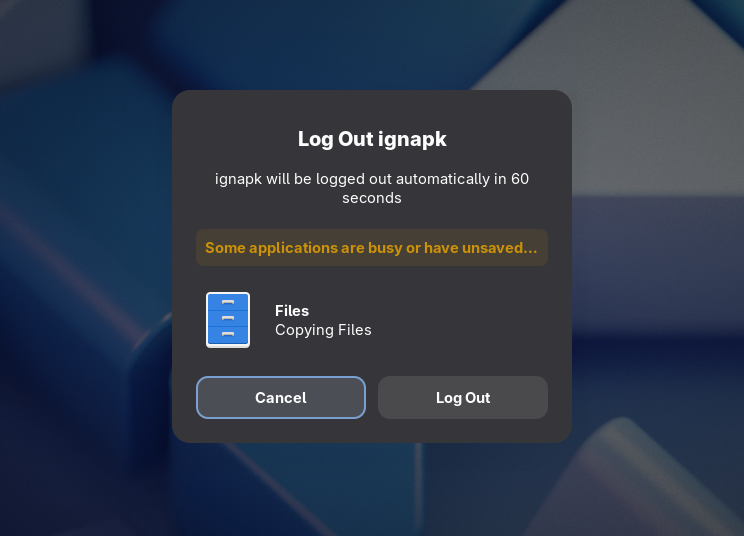

| Trash after emptying in Nautilus, are the files really gone? |

It all started with a 2009 Ubuntu launchpad ticket, reported against Nautilus. The user found 70 GB worth of files using disk analyzer in the ~/.local/share/Trash/expunged directory, even though they had emptied it with graphical interface. They did realize the offending files belonged to another user, however, they couldn’t reproduce it easily at first. After all, when you try to move to trash a file or a directory not belonging to you, you would usually be correctly informed that you don’t have necessary permissions, and perhaps even offer to permanently delete them instead. So what was so special about this case?

First let’s get a better view of when we can and when we can’t permanently delete files, something that is done at the end of a successful trash emptying operation. We’ll focus only on the owners of relevant files, since other factors, such as file read/write/execute permissions, can be adjusted freely by their owners, and that’s what trash implementations will do for you. Here are cases where you CAN delete files:

– when a file is in a directory owned by you, you can always delete it

– when a directory is in a directory owned by you and it’s owned by you, you can obviously delete it

– when a directory is in a directory owned by you but you don’t own it, and it’s empty, you can surprisingly delete it as well

So to summarize, no matter who the owner of the file or a directory is, if it’s in a directory owned by you, you can get rid of it. There is one exception to this – the directory must be empty, otherwise, you will not be able to remove neither it, nor its including files. Which takes us to an analogous list for cases where you CANNOT delete files:

– when a directory is in a directory owned by you but you don’t own it, and it’s not empty, you can’t delete it.

– when a file is in a directory NOT owned by you, you can’t delete it

– when a directory is in a directory NOT owned by you, you can’t delete it either

In contrast with removing files in a directory you own, when you are not the owner of the parent directory, you cannot delete any of the child files and directories, without exceptions. This is actually the reason for the one case where you can’t remove something from a directory you own – to remove a non-empty directory, first you need to recursively delete all of its including files and directories, and you can’t do that if the directory is not owned by you.

Now let’s look inside the trash can, or rather how it functions – the reason for separating permanently deleting and trashing operations, is obvious – users are expected to change their mind and be able to get their files back on a whim, so there’s a need for a middle step. That’s where the Trash specification comes, providing a common way in which all “Trash can” implementation should store, list, and restore trashed files, even across different filesystems – Nautilus Trash feature is one of the possible implementations. The way the trashing works is actually moving files to the $XDG_DATA_HOME/Trash/files directory and setting up some metadata to track their original location, to be able to restore them if needed. Only when the user empties the trash, are they actually deleted. If it’s all about moving files, specifically outside their previous parent directory (i.e. to Trash), let’s look at cases where you CAN move files:

– when a file is in a directory owned by you, you can move it

– when a directory is in a directory owned by you and you own it, you can obviously move it

We can see that the only exception when moving files in a directory you own, is when the directory you’re moving doesn’t belong to you, in which case you will be correctly informed you don’t have permissions. In the remaining cases, users are able to move files and therefore trash them. Now what about the cases where you CANNOT move files?

– when a directory is in a directory owned by you but you don’t own it, you can’t move it

– when a file is in a directory NOT owned by you, you can’t move it either

– when a directory is in a directory NOT owned by you, you still can’t move it

In those cases Nautilus will either not expose the ability to trash files, or will tell user about the error, and the system is working well – even if moving them was possible, permanently deleting files in a directory not owned by you is not supported anyway.

So, where’s the catch? What are we missing? We’ve got two different operations that can succeed or fail given different circumstances, moving (trashing) and deleting. We need to find a situation, where moving a file is possible, and such overlap exists, by chaining the following two rules:

– when a directory A is in a directory owned by you and it’s owned by you, you can obviously move it

– when a directory B is in a directory A owned by you but you don’t own it, and it’s not empty, you can’t delete it.

So a simple way to reproduce was found, precisely:

mkdir -p test/root

touch test/root/file

sudo chown root:root test/root

Afterwards trashing and emptying in Nautilus or gio trash command will result in the files not being deleted, and left in the ~/.local/share/Trash/expunged, which is used by the gvfsd-trash as an intermediary during emptying operation. The situations where that can happen are very rare, but they do exist – personally I have encountered this when manually cleaning container files created by podman in ~/.local/share/containers, which I arguably I shouldn’t be doing in the first place, and rather leave it up to the podman itself. Nevertheless, it’s still possible from the user perspective, and should be handled and prevented correctly. That’s exactly what was done, a ticket was submitted and moved to appropriate place, which turned out to be glib itself, and I have submitted a MR that was merged – now both Nautilus and gio trash will recursively check for this case, and prevent you from doing this. You can expect it in the next glib release 2.85.1.

On the ending notes I want to thank the glib maintainer Philip Withnall who has walked me through on the required changes and reviewed them, and ask you one thing: is your ~/.local/share/Trash/expunged really empty? 🙂