Linux distributions have a problem with WebKit security.

Major desktop browsers push automatic security updates directly to users on a regular basis, so most users don’t have to worry about security updates. But Linux users are dependent on their distributions to release updates. Apple fixed over 100 vulnerabilities in WebKit last year, so getting updates out to users is critical.

This is the story of how that process has gone wrong for WebKit.

Before we get started, a few disclaimers. I want to be crystal clear about these points:

- This post does not apply to WebKit as used in Apple products. Apple products receive regular security updates.

- WebKitGTK+ releases regular security updates upstream. It is safe to use so long as you apply the updates.

- The opinions expressed in this post are my own, not my employer’s, and not the WebKit project’s.

Browser Security in a Nutshell

Web engines are full of security vulnerabilities, like buffer overflows and use-after-frees. The details don’t matter; what’s important is that skilled attackers can turn these vulnerabilities into exploits, using carefully-crafted HTML to gain total control of your user account on your computer (or your phone). They can then install malware, read all the files in your home directory, use your computer in a botnet to attack websites, and do basically whatever they want with it.

If the web engine is sandboxed, then a second type of attack, called a sandbox escape, is needed. This makes it dramatically more difficult to exploit vulnerabilities. Chromium has a top-class Linux sandbox. WebKit does have a Linux sandbox, but it’s not any good, so it’s (rightly) disabled by default. Firefox does not have a sandbox due to major architectural limitations (which Mozilla is working on).

For this blog post, it’s enough to know that attackers use crafted input to exploit vulnerabilities to gain control of your computer. This is why it’s not a good idea to browse to dodgy web pages. It also explains how a malicious email can gain control of your computer. Modern email clients render HTML mail using web engines, so malicious emails exploit many of the same vulnerabilities that a malicious web page might. This is one reason why good email clients block all images by default: image rendering, like HTML rendering, is full of security vulnerabilities. (Another reason is that images hosted remotely can be used to determine when you read the email, violating your privacy.)

WebKit Ports

To understand WebKit security, you have to understand the concept of WebKit ports, because different ports handle security updates differently.

While most code in WebKit is cross-platform, there’s a large amount of platform-specific code as well, to improve the user and developer experience in different environments. Different “ports” run different platform-specific code. This is why two WebKit-based browsers, say, Safari and Epiphany (GNOME Web), can display the same page slightly differently: they’re using different WebKit ports.

Currently, the WebKit project consists of six different ports: one for Mac, one for iOS, two for Windows (Apple Windows and WinCairo), and two for Linux (WebKitGTK+ and WebKitEFL). There are some downstream ports as well; unlike the aforementioned ports, downstream ports are, well, downstream, and not part of the WebKit project. The only one that matters for Linux users is QtWebKit.

If you use Safari, you’re using the Mac or iOS port. These ports get frequent security updates from Apple to plug vulnerabilities, which users receive via regular updates.

Everything else is broken.

Since WebKit is not a system library on Windows, Windows applications must bundle WebKit, so each application using WebKit must be updated individually, and updates are completely dependent on the application developers. iTunes, which uses the Apple Windows port, does get regular updates from Apple, but beyond that, I suspect most applications never get any security updates. This is a predictable result, the natural consequence of environments that require bundling libraries.

(This explains why iOS developers are required to use the system WebKit rather than bundling their own: Apple knows that app developers will not provide security updates on their own, so this policy ensures every iOS application rendering HTML gets regular WebKit security updates. Even Firefox and Chrome on iOS are required to use the system WebKit; they’re hardly really Firefox or Chrome at all.)

The same scenario applies to the WinCairo port, except this port does not have releases or security updates. Whereas the Apple ports have stable branches with security updates, with WinCairo, companies take a snapshot of WebKit trunk, make their own changes, and ship products with that. Who’s using WinCairo? Probably lots of companies; the biggest one I’m aware of uses a WinCairo-based port in its AAA video games. It’s safe to assume few to no companies are handling security backports for their downstream WinCairo branches.

Now, on to the Linux ports. WebKitEFL is the WebKit port for the Enlightenment Foundation Libraries. It’s not going to be found in mainstream Linux distributions; it’s mostly used in embedded devices produced by one major vendor. If you know anything at all about the internet of things, you know these devices never get security updates, or if they do, the updates are superficial (updating only some vulnerable components and not others), or end a couple months after the product is purchased. WebKitEFL does not bother with pretense here: like WinCairo, it has never had security updates. And again, it’s safe to assume few to no companies are handling security backports for their downstream branches.

None of the above ports matter for most Linux users. The ports available on mainstream Linux distributions are QtWebKit and WebKitGTK+. Most of this blog will focus on WebKitGTK+, since that’s the port I work on, and the port that matters most to most of the people who are reading this blog, but QtWebKit is widely-used and deserves some attention first.

It’s broken, too.

QtWebKit

QtWebKit is the WebKit port used by Qt software, most notably KDE. Some cherry-picked examples of popular applications using QtWebKit are Amarok, Calligra, KDevelop, KMail, Kontact, KTorrent, Quassel, Rekonq, and Tomahawk. QtWebKit provides an excellent Qt API, so in the past it’s been the clear best web engine to use for Qt applications.

After Google forked WebKit, the QtWebKit developers announced they were switching to work on QtWebEngine, which is based on Chromium, instead. This quickly led to the removal of QtWebKit from the WebKit project. This was good for the developers of other WebKit ports, since lots of Qt-specific code was removed, but it was terrible for KDE and other QtWebKit users. QtWebKit is still maintained in Qt and is getting some backports, but from a quick check of their git repository it’s obvious that it’s not receiving many security updates. This is hardly unexpected; QtWebKit is now years behind upstream, so providing security updates would be very difficult. There’s not much hope left for QtWebKit; these applications have hundreds of known vulnerabilities that will never be fixed. Applications should port to QtWebEngine, but for many applications this may not be easy or even possible.

Update: As pointed out in the comments, there is some effort to update QtWebKit. I was aware of this and in retrospect should have mentioned this in the original version of this article, because it is relevant. Keep an eye out for this; I am not confident it will make its way into upstream Qt, but if it does, this problem could be solved.

WebKitGTK+

WebKitGTK+ is the port used by GTK+ software. It’s most strongly associated with its flagship browser, Epiphany, but it’s also used in other places. Some of the more notable users include Anjuta, Banshee, Bijiben (GNOME Notes), Devhelp, Empathy, Evolution, Geany, Geary, GIMP, gitg, GNOME Builder, GNOME Documents, GNOME Initial Setup, GNOME Online Accounts, GnuCash, gThumb, Liferea, Midori, Rhythmbox, Shotwell, Sushi, and Yelp (GNOME Help). In short, it’s kind of important, not only for GNOME but also for Ubuntu and Elementary. Just as QtWebKit used to be the web engine for choice for Qt applications, WebKitGTK+ is the clear choice for GTK+ applications due to its nice GObject APIs.

Historically, WebKitGTK+ has not had security updates. Of course, we released updates with security fixes, but not with CVE identifiers, which is how software developers track security issues; as far as distributors are concerned, without a CVE identifier, there is no security issue, and so, with a few exceptions, distributions did not release our updates to users. For many applications, this is not so bad, but for high-risk applications like web browsers and email clients, it’s a huge problem.

So, we’re trying to improve. Early last year, my colleagues put together our first real security advisory with CVE identifiers; the hope was that this would encourage distributors to take our updates. This required data provided by Apple to WebKit security team members on which bugs correspond to which CVEs, allowing the correlation of Bugzilla IDs to Subversion revisions to determine in which WebKitGTK+ release an issue has been fixed. That data is critical, because without it, there’s no way to know if an issue has been fixed in a particular release or not. After we released this first advisory, Apple stopped providing the data; this was probably just a coincidence due to some unrelated internal changes at Apple, but it certainly threw a wrench in our plans for further security advisories.

This changed in November, when I had the pleasure of attending the WebKit Contributors Meeting at Apple’s headquarters, where I was finally able meet many of the developers I had interacted with online. At the event, I gave a presentation on our predicament, and asked Apple to give us information on which Bugzilla bugs correspond to which CVEs. Apple kindly provided the necessary data a few weeks later.

During the Web Engines Hackfest, a yearly event that occurs at Igalia’s office in A Coruña, my colleagues used this data to put together WebKitGTK+ Security Advisory WSA-2015-0002, a list of over 130 vulnerabilities disclosed since the first advisory. (The Web Engines Hackfest was sponsored by Igalia, my employer, and by our friends at Collabora. I’m supposed to include their logos here to advertise how cool it is that they support the hackfest, but given all the doom and gloom in this post, I decided perhaps they would perhaps prefer not to have their logos attached to it.)

Note that 130 vulnerabilities is an overcount, as it includes some issues that are specific to the Apple ports. (In the future, we’ll try to filter these out.) Only one of the issues — a serious error in the networking backend shared by WebKitGTK+ and WebKitEFL — resided in platform-specific code; the rest of the issues affecting WebKitGTK+ were all cross-platform issues. This is probably partly because the trickiest code is cross-platform code, and partly because security researchers focus on Apple’s ports.

Anyway, we posted WSA-2015-0002 to the oss-security mailing list to make sure distributors would notice, crossed our fingers, and hoped that distributors would take the advisory seriously. That was one month ago.

Distribution Updates

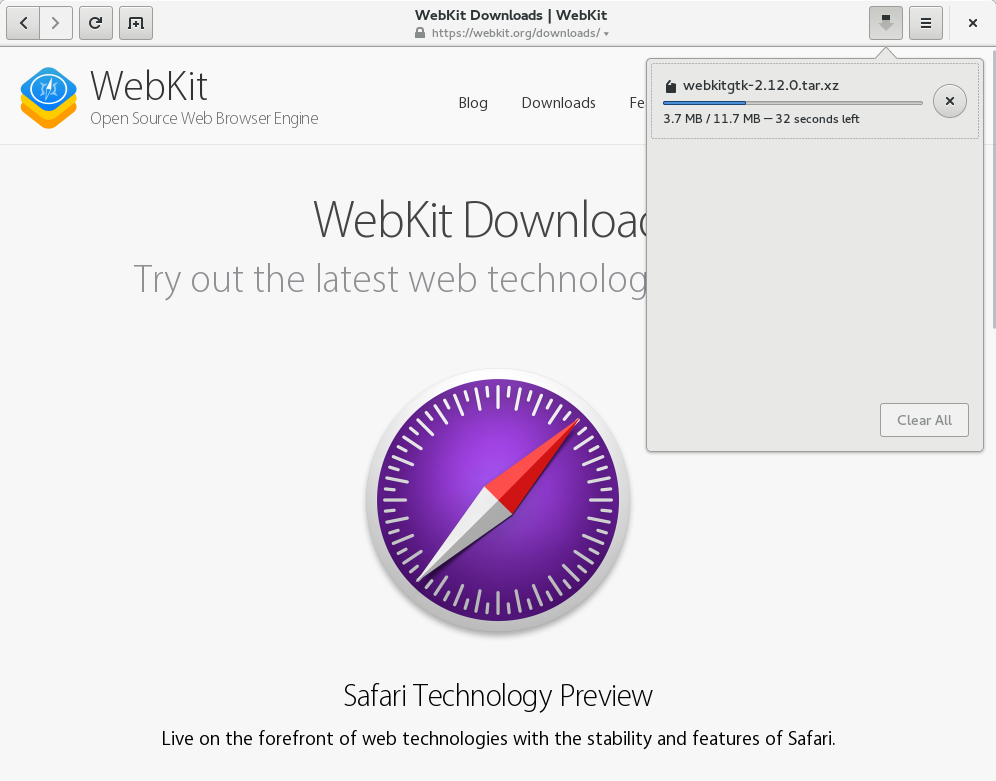

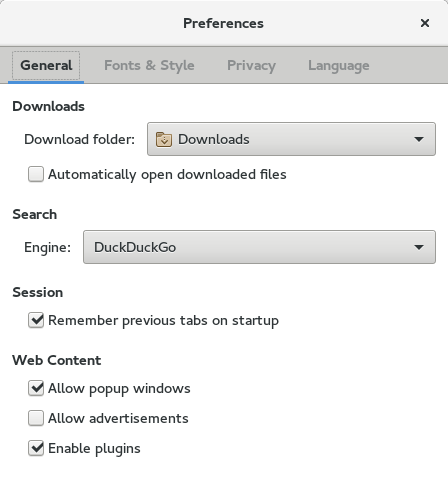

There are basically three different approaches distributions can take to software updates. The first approach is to update to the latest stable upstream version as soon as, or shortly after, it’s released. This is the strategy employed by Arch Linux. Arch does not provide any security support per se; it’s not necessary, so long as upstream projects release real updates for security problems and not simply patches. Accordingly, Arch almost always has the latest version of WebKitGTK+.

The second main approach, used by Fedora, is to provide only stable release updates. This is more cautious, reflecting that big updates can break things, so they should only occur when upgrading to a new version of the operating system. For instance, Fedora 22 shipped with WebKitGTK+ 2.8, so it would release updates to new 2.8.x versions, but not to WebKitGTK+ 2.10.x versions.

The third approach, followed by most distributions, is to take version upgrades only rarely, or not at all. For smaller distributions this may be an issue of manpower, but for major distributions it’s a matter of avoiding regressions in stable releases. Holding back on version updates actually works well for most software. When security problems arise, distribution maintainers for major distributions backport fixes and release updates. The problem is that this not feasible for web engines; due to the huge volume of vulnerabilities that need fixed, security issues can only practically be handled upstream.

So what’s happened since WSA-2015-0002 was released? Did it convince distributions to take WebKitGTK+ security seriously? Hardly. Fedora is the only distribution that has made any changes in response to WSA-2015-0002, and that’s because I’m one of the Fedora maintainers. (I’m pleased to announce that we have a 2.10.7 update headed to both Fedora 23 and Fedora 22 right now. In the future, we plan to release the latest stable version of WebKitGTK+ as an update to all supported versions of Fedora shortly after it’s released upstream.)

Ubuntu

Ubuntu releases WebKitGTK+ updates somewhat inconsistently. For instance, Ubuntu 14.04 came with WebKitGTK+ 2.4.0. 2.4.8 is available via updates, but even though 2.4.9 was released upstream over eight months ago, it has not yet been released as an update for Ubuntu 14.04.

By comparison, Ubuntu 15.10 (the latest release) shipped with WebKitGTK+ 2.8.5, which has never been updated; it’s affected by about 40 vulnerabilities fixed in the latest upstream release. Ubuntu organizes its software into various repositories, and provides security support only to software in the main repository. This version of WebKitGTK+ is in Ubuntu’s “universe” repository, not in main, so it is excluded from security support. Ubuntu users might be surprised to learn that a large portion of Ubuntu software is in universe and therefore excluded from security support; this is in contrast to almost all other distributions, which typically provide security updates for all the software they ship.

I’m calling out Ubuntu here not because it is specially-negligent, but simply because it is our biggest distributor. It’s not doing any worse than most of our other distributors.

Debian

Debian provides WebKit updates to users running unstable, and to testing except during freeze periods, but not to released version of Debian. Debian is unique in that it has a formal policy on WebKit updates. Here it is, reproduced in full:

Debian 8 includes several browser engines which are affected by a steady stream of security vulnerabilities. The high rate of vulnerabilities and partial lack of upstream support in the form of long term branches make it very difficult to support these browsers with backported security fixes. Additionally, library interdependencies make it impossible to update to newer upstream releases. Therefore, browsers built upon the webkit, qtwebkit and khtml engines are included in Jessie, but not covered by security support. These browsers should not be used against untrusted websites.

For general web browser use we recommend Iceweasel or Chromium.

Chromium – while built upon the Webkit codebase – is a leaf package, which will be kept up-to-date by rebuilding the current Chromium releases for stable. Iceweasel and Icedove will also be kept up-to-date by rebuilding the current ESR releases for stable.

(Iceweasel and Icedove are Debian’s de-branded versions of Firefox and Thunderbird, the product of an old trademark spat with Mozilla.)

Debian is correct that we do not provide long term support branches, as it would be very difficult to backport security fixes. But it is not correct that “library interdependencies make it impossible to update to newer upstream releases.” This might have been true in the past, but for several years now, we have avoided requiring new versions of libraries whenever it would cause problems for distributions, and — with one big exception that I will discuss below — we ensure that each release maintains both API and ABI compatibility. (Distribution maintainers should feel free to get in touch if we accidentally introduce some compatibility issue for your distribution; if you’re having trouble taking our updates, we want to help. I recently worked with openSUSE to make sure WebKitGTK+ can still be compiled with GCC 4.8, for example.)

The risk in releasing updates is that WebKitGTK+ is not a leaf package: a bad update could break some application. This seems to me like a good reason for application maintainers to carefully test the updates, rather than a reason to withhold security updates from users, but it’s true there is some risk here. One possible solution would be to have two different WebKitGTK+ packages, say, webkitgtk-secure, which would receive updates and be used by high-risk software like web browsers and email clients, and a second webkitgtk-stable package that would not receive updates to reduce regression potential.

Recommended Distributions

We regularly receive bug reports from users with very old versions of WebKit, who trust their distributors to handle security for them and might not even realize they are running ancient, unsafe versions of WebKit. I strongly recommend using a distribution that releases WebKitGTK+ updates shortly after they’re released upstream. That is currently only Arch and Fedora. (You can also safely use WebKitGTK+ in Debian testing — except during its long freeze periods — and Debian unstable, and maybe also in openSUSE Tumbleweed, and (update) also in Gentoo testing. Just be aware that the stable releases of these distributions are currently not receiving our security updates.) I would like to add more distributions to this list, but I’m currently not aware of any more that qualify.

The Great API Break

So, if only distributions would ship the latest release of WebKitGTK+, then everything would be good, right? Nope, because of a large API change that occurred two and a half years ago, called WebKit2.

WebKit (an API layer within the WebKit project) and WebKit2 are two separate APIs around WebCore. WebCore is the portion of the WebKit project that Google forked into Blink; it’s too low-level to be used directly by applications, so it’s wrapped by the nicer WebKit and WebKit2 APIs. The difference between the WebKit and WebKit2 APIs is that WebKit2 splits work into multiple secondary processes. Asides from the UI process, an application will have one or many separate web processes (for the actual page rendering), possibly a separate network process, and possibly a database process for IndexedDB. This is good for security, because it allows the secondary processes to be sandboxed: the web process is the one that’s likely to be compromised first, so it should not have the ability to access the filesystem or the network. (Remember, though, that there is no Linux sandbox yet, so this is currently only a theoretical benefit.) The other main benefit is robustness. If a web site crashes the renderer, only a single web process crashes (corresponding to one tab in Epiphany), not the entire browser. UI process crashes are comparatively rare.

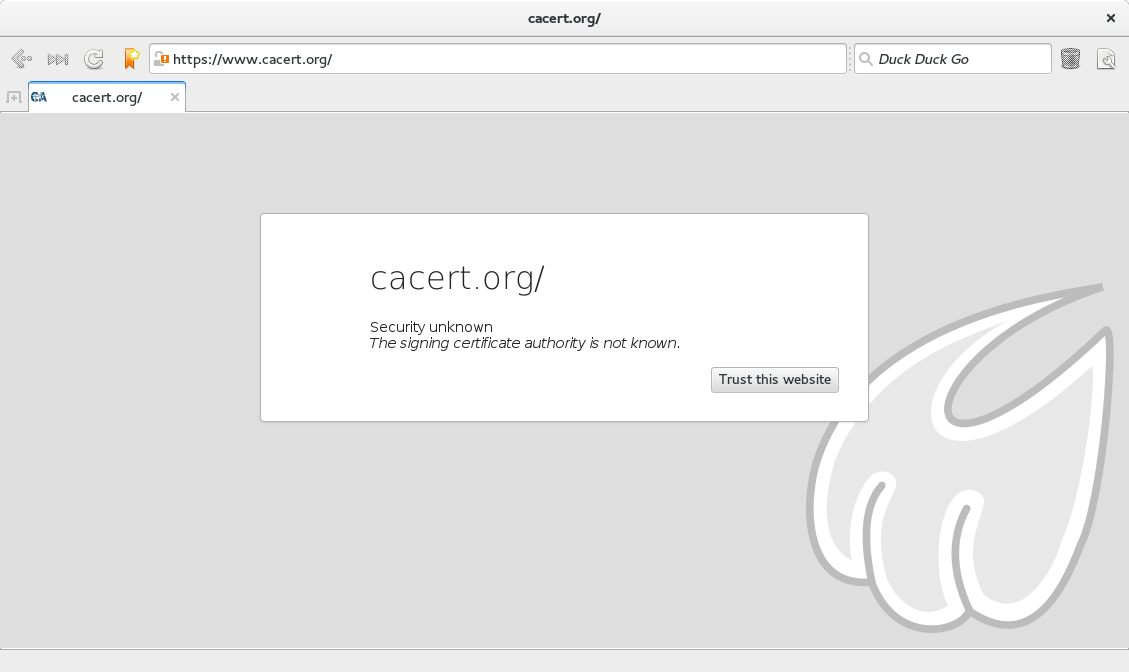

Intermission: Certificate Verification

Another advantage provided by the API change is the opportunity to handle HTTPS connections more securely. In the original WebKitGTK+ API, applications must handle certificate verification on their own. This was a serious mistake; predictably, applications performed no verification at all, or did so improperly. For instance, take this Shotwell bug which is not fixed in any released version of Shotwell, or this Banshee bug which is still open. Probably many more applications are affected, because I have not done a comprehensive check. The new API is secure by default; applications can ignore verification errors, but only if they go out of their way to do so.

Remember that even though WebKitGTK+ 2.4.9 was released upstream over eight months ago, Ubuntu 14.04 is still on 2.4.8? It’s worth mentioning that 2.4.9 contains the fix for that serious networking backend issue I mentioned earlier (CVE-2015-2330). The bug is that TLS certificate verification was not performed until an HTTP response was received from the server; it’s supposed to be performed before sending an HTTP request, to prevent secure cookies from leaking. This is a disaster, as attackers can easily use it to get your session cookie and then control your user account on most websites. (Credit to Ross Lagerwall for reporting that issue.) We reported this separately to oss-security due to its severity, but that was not enough to convince distributions to update. But most applications in Ubuntu 14.04, including Epiphany and Midori, would not even benefit from this fix, because the change only affects WebKit2; remember, there’s no certificate verification in the original WebKitGTK+ API. (Modern versions of Epiphany do use WebKit2, but not the old version included in Ubuntu 14.04.) Old versions of Epiphany and Midori load pages even if certificate verification fails; the verification result is only used to change the status of a security indicator, basically giving up your session cookies to attackers.

Removing WebKit1

WebKit2 has been around for Mac and iOS for longer, but the first stable release for WebKitGTK+ was the appropriately-versioned WebKitGTK+ 2.0, in March 2013. This release actually contained three different APIs: webkitgtk-1.0, webkitgtk-3.0, and webkit2gtk-3.0. webkitgtk-1.0 was the original API, used by GTK+ 2 applications. webkitgtk-3.0 was the same thing for GTK+ 3 applications, and webkit2gtk-3.0 was the new WebKit2 API, available only for GTK+ 3 applications.

Maybe it should have remained that way.

But, since the original API was a maintenance burden and not as stable or robust as WebKit2, it was deleted after the WebKitGTK+ 2.4 release in March 2014. Applications had had a full year to upgrade; surely that was long enough, right? The original WebKit API layer is still maintained for the Mac, iOS, and Windows ports, but the GTK+ API for it is long gone. WebKitGTK+ 2.6 (September 2014) was released with only one API, webkit2gtk-4.0, which was basically the same as webkit2gtk-3.0 except for a couple small fixes; most applications were able to upgrade by simply changing the version number. Since then, we have maintained API and ABI compatibility for webkit2gtk-4.0, and intend to do so indefinitely, hopefully until GTK+ 4.0.

A lot of good that does for applications using the API that was removed.

WebKit2 Adoption

While upgrading to the WebKit2 API will be easy for most applications (it took me ten minutes to upgrade GNOME Initial Setup), for many others it will be a significant challenge. Since rendering occurs out of process in WebKit2, the DOM API can only be accessed by means of a shared object injected into the web process. For applications that perform only a small amount of DOM manipulation, this is a minor inconvenience compared to the old API. For applications that use extensive DOM manipulation — the email clients Evolution and Geary, for instance — it’s not just an inconvenience, but a major undertaking to upgrade to the new API. Worse, some applications (including both Geary and Evolution) placed GTK+ widgets inside the web view; this is no longer possible, so such widgets need to be rewritten using HTML5. Say nothing of applications like GIMP and Geany that are stuck on GTK+ 2. They first have to upgrade to GTK+ 3 before they can consider upgrading to modern WebKitGTK+. GIMP is working on a GTK+ 3 port anyway (GIMP uses WebKitGTK+ for its help browser), but many applications like Geany (the IDE, not to be confused with Geary) are content to remain on GTK+ 2 forever. Such applications are out of luck.

As you might expect, most applications are still using the old API. How does this work if it was already deleted? Distributions maintain separate packages, one for old WebKitGTK+ 2.4, and one for modern WebKitGTK+. WebKitGTK+ 2.4 has not had any updates since last May, and the last real comprehensive security update was over one year ago. Since then, almost 130 vulnerabilities have been fixed in newer versions of WebKitGTK+. But since distributions continue to ship the old version, few applications are even thinking about upgrading. In the case of the email clients, the Evolution developers are hoping to upgrade later this year, but Geary is completely dead upstream and probably will never be upgraded. How comfortable are you with using an email client that has now had no security updates for a year?

(It’s possible there might be a further 2.4 release, because WebKitGTK+ 2.4 is incompatible with GTK+ 3.20, but maybe not, and if there is, it certainly will not include many security fixes.)

Fixing Things

How do we fix this? Well, for applications using modern WebKitGTK+, it’s a simple problem: distributions simply have to start taking our security updates.

For applications stuck on WebKitGTK+ 2.4, I see a few different options:

- We could attempt to provide security backports to WebKitGTK+ 2.4. This would be very time consuming and therefore very expensive, so count this out.

- We could resurrect the original webkitgtk-1.0 and webkitgtk-3.0 APIs. Again, this is not likely to happen; it would be a lot of work to restore them, and they were removed to reduce maintenance burden in the first place. (I can’t help but feel that removing them may have been a mistake, but my colleagues reasonably disagree.)

- Major distributions could remove the old WebKitGTK+ compatibility packages. That will force applications to upgrade, but many will not have the manpower to do so: good applications will be lost. This is probably the only realistic way to fix the security problem, but it’s a very unfortunate one. (But don’t forget about QtWebKit. QtWebKit is based on an even older version of WebKit than WebKitGTK+ 2.4. It doesn’t make much sense to allow one insecure version of WebKit but not another.)

Or, a far more likely possibility: we could do nothing, and keep using insecure software.