This post is part of an ongoing series about the overview design changes which are being worked on for GNOME 40. (For previous posts, see here.)

Ongoing user research has been a major feature of this design initiative, and I would say that it is by far the best researched project that I have worked on. Our research has informed the design as it has proceeded, resulting in particular design choices and changes, which have improved the overall design and will make it a better experience for users. As a result of this, we have a much greater degree of confidence in the designs.

This post is intended as a general overview of the research that we’ve been doing. I’m excited to share this, as a way of explaining how the design came about, as well as sharing some of the insights that we’ve found along the way.

What we did

In total, we conducted six separate research exercises as part of this initiative. These ran alongside the design and development effort, in order to answer the questions we had at each stage of the process.

Many of the research exercises were small and limited. This reflected our ambition to use a lean approach, which suited the limited resources we had available. These smaller exercises were supplemented with a larger piece of paid research, which was conducted for us by an external research company. In what follows I’ll go through each exercise in order, and give a brief description of what was done and what we found out.

So far the data from our research isn’t publicly available, largely because it contains personal information about test participants which can’t be shared. However, we do plan on making a version of the data available, with any identifying information removed.

1. Exploratory interviews

I already blogged about this exercise back in September. A summary: the initial interviews were an exploratory, sensitising, exercise, to find out how existing users used and felt about GNOME Shell. We spoke to seven GNOME users who had a range of roles and technical expertise. Each participant showed us their desktop setup and how they used it, and we asked them questions to find out how the existing shell design was working for them.

We found out a bunch of valuable things from those early interviews. A good portion of the people we spoke to really liked the shell, particularly its minimalism and the lack of distractions. We also discovered a number of interesting behaviours and user types around window and workspace usage.

2. Initial behavioural survey

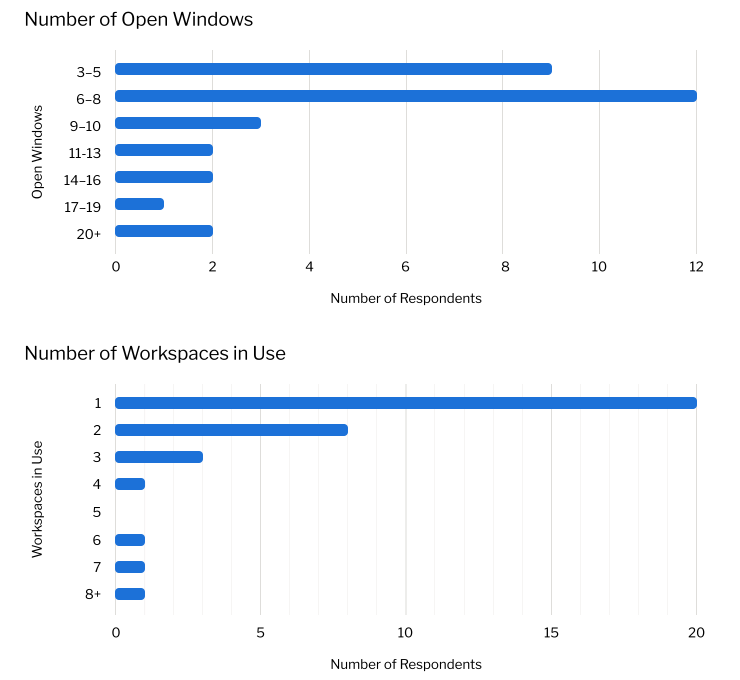

The initial survey exercise was also covered in my September blog post. It was intended to provide some numbers on app, window and workspace usage, in order to provide some insight into the range of behaviours that any design changes needed to accommodate.

The survey was a deliberately quick exercise. We found out that most people had around 8 open windows, and that the number of people with a substantially higher number of open windows was low. We also found that most people were only using a single workspace, and that high numbers of workspaces in use (say, above six) was quite rare.

3. Running apps experiment

During the early design phase, the design team was interested in the role of the running apps in the dash. To explore this, I ran a little experiment: I got colleagues to install an extension which removes running apps from the dash, and asked them to record any issues that they experienced.

We found that most people got along just fine without running apps in the dash. Despite this, in the end we decided to keep the running apps, based on other anecdotal reports we’d seen.

4. External user testing

Thanks to support by Endless, we were lucky to have the opportunity to contract out some research work. This was carried out by Insights and Experimentation Agency Brooks Bell and was contracted under the umbrella of the GNOME Foundation.

The research occurred at a point in the process where we were weighing up key design decisions, which the research was designed to help us answer in an informed manner.

Methodology

The research itself consisted of 20 moderated user testing sessions, which were conducted remotely. Each participant tested GNOME 3.38 and then either a prototype of the new design or Endless OS. This provided us with a means to compare how each of the three desktops performed, with a view to identifying the strengths and weaknesses of each.

Each session involved a combination of exploration and evaluation. Participants were interviewed about their typical desktop usage, and were invited to recreate a typical desktop session within the test environment. They were then asked to perform some basic tasks. After testing both environments, they were required to fill in a post-test survey to give feedback on the two desktops they had tried.

Research participants included both existing GNOME users, as well as users who had never used GNOME before. The sample included a range of technical abilities and experience levels. It also included a mix of professional and personal computer users. The study was structured in such a way that we could analyse the differences between different user groups, so we could get a sense of how each desktop performed with different user groups. Participants were recruited from six countries: Brazil, Canada, Germany, Italy, United Kingdom and the USA.

Brooks Bell were a great firm to work with. Our own design and development team were able to have detailed planning conversations with them, as well as lengthy sessions to discuss the research findings. We were also given access to all the research data, to enable us to do our own analysis work.

Findings

The external research provided a wealth of useful information and analysis. It addressed the specific research questions that we had for the study, but also went further to address general questions about how and why the participants responded to the designs in the way that they did, as well as identifying a number of unrelated design issues which we hope to address in future releases.

One of the themes in the research was the degree to which users positively responded to UI conventions with which they were already familiar. This was reflected in both how respondents responded to the designs in general, as well as how successfully they were able to use specific aspects of them. For example, interactions with the app grid and dash were typically informed by the participants’ experiences with similar UIs from other platforms.

This might seem like an obvious finding, however the utility of the research was in demonstrating how this general principle played out in the specific context of our designs. It was also very interesting to see how conventions from both mobile and desktop informed user behaviour.

In terms of specific findings, there wasn’t a single clear story from the tests, but rather multiple overlapping findings.

Existing GNOME users generally felt comfortable with the desktop they already use. They often found the new design to be exciting and liked the look and feel, and some displayed a negative reaction to Endless, due to its similarity with Windows.

“I like the workspaces moving sideways, it feels more comfortable to switch between them.”

—Comment on the prototype by an existing GNOME user

All users seemed to find the new workspace design to be more engaging and intuitive, in comparison with the workspaces in GNOME 3.38. This was one particular area where the new design seemed to perform better than existing GNOME Shell.

“[It feels] quicker to navigate through. It [has a] screen where I can view my desktop at the top and the apps at the bottom, this makes it quicker to navigate.”

—Comment on the prototype by a non-GNOME user

On the other hand, new users generally got up to speed more quickly with Endless OS, often due to its similarity to Windows. Many of these testers found the bottom panel to be an easy way to switch applications. They also made use of the minimize button. In comparison, both GNOME 3.38 and the prototype generally took more adjustment for these users.

“I really liked that it’s similar to the Windows display that I have.”

—Comment on Endless OS by a non-GNOME user

5. Endless user testing

The final two research exercises we conducted were used to fill in specific gaps in our existing knowledge, largely as a validation exercise for the design we were working towards. The first of these consisted of 10 remote user testing sessions, conducted by Endless with participants from Guatemala, Kenya and the USA. These participants were picked from particular demographics that are of importance to Endless, particularly young users with limited computing experience.

Each test involved the participant running through a series of basic desktop tasks. Like the tests run by Brooks Bell, these sessions had a comparative element, with participants trying both Endless OS and the prototype of the new design. In many respects, these sessions confirmed what we’d already found through the Brooks Bell study, with participants both responding well to the workspace design in the prototype, and having to adjust to designs that were unfamiliar to them.

“Everything happens naturally after you go to Activities. The computer is working for you, you’re not working for it”

—Tester commenting on the new design

6. Diary study

The diary study was intended to identify any issues that might be encountered with long-term usage, which might have been missed in the previous user tests. Workspaces and multi-monitor usage were a particular focus for this exercise, and participants were selected based on whether they use these features.

The five diary study participants installed the prototype implementation and used it for a week. I interviewed them before the test to find out their existing usage patterns, then twice more over the test period, to see how they were finding the new design. The participant also kept a record of their experiences with the new design, which we referred back to during the interviews.

This exercise didn’t turn up any specific issues with multi-monitor or workspace usage, despite including participants who used those features. In all the participants generally had a positive response to the new design and preferred it over the existing GNOME shell they were using. It should be mentioned that this wasn’t universal however.

7. Community testing and feedback

While community testing isn’t strictly a research exercise, it has nevertheless been an important part of our data-driven approach for this initiative. One thing that we’ve managed to do relatively successfully is have a range of easy ways to test the new design. This was a priority for us from the start and has resulted in us being able to have a good round of feedback and design adjustment.

It should be noted that those of us on the design side have had detailed follow-up conversations with those who have provided feedback, in order to ensure that we have a complete understanding of the issues as described. (This often requires having background knowledge about users setup and usage patterns.) I have personally found this to be an effective way of developing empathy and understanding. It is also a good example of how our previous research has helped, by providing a framework within which to understand feedback.

The main thing that we have got from this stage of the process is testing with a wider variety of setups, which in particular has informed the multi-monitor and workspace aspects of the design.

Reflection

As I wrote in the introduction to this post, GNOME has never had a design initiative that has been so heavily accompanied by research work. The research we’ve done has undoubtedly improved the design that we’re pursuing for GNOME 40. It has also enabled us to proceed with a greater degree of confidence than we would have otherwise had.

We’re not claiming that every aspect of the research we’ve done has been perfect or couldn’t have been improved. There are gaps which, if were able to do it all again, we would have liked to have filled. But perfect is the enemy of good and doing some research – irrespective of its issues – is certainly better than doing none at all. Add to this the fact that we have been doing research in the context of an upstream open source project with limited resources, and I think we can be proud of what we’ve achieved.

When you put together the lessons from each of the research exercises we’ve done, the result is a picture of different user segments having somewhat different interests and requirements. On the one hand, we have the large number of people who have never used GNOME or an open source desktop, to whom a familiar design is one that is generally preferable. On the other hand, there are users who don’t want a carbon copy of the proprietary desktops, and there are (probably more technical) users who are particularly interested in a more minimal, pared back experience which doesn’t distract them from their work.

The best way for the GNOME project to navigate this landscape is a tricky question, and it involves a difficult balancing act. However, with the changes that are coming in GNOME 40, we hope that we are starting out on that path, with an approach that both adopts some familiar conventions from other platforms, while developing and refining GNOME’s unique strengths.