It’s that time of year again! A new major release of Epiphany is out now, representing another six months of incremental progress. That’s a fancy way of saying that not too much has changed (so how did this blog post get so long?). It’s not for lack of development effort, though. There’s actually lot of action in git master and on sidebranches right now, most of it thanks to my awesome Google Summer of Code students, Gabriel Ivascu and Iulian Radu. However, I decided that most of the exciting changes we’re working on would be deferred to Epiphany 3.24, to give them more time to mature and to ensure quality. And since this is a blog post about Epiphany 3.22, that means you’ll have to wait until next time if you want details about the return of the traditional address bar, the brand-new user interface for bookmarks, the new support for syncing data between Epiphany browsers on different computers with Firefox Sync, or Prism source code view, all features that are brewing for 3.24. This blog also does not cover the cool new stuff in WebKitGTK+ 2.14, like new support for copy/paste and accelerated compositing in Wayland.

New stuff

So, what’s new in 3.22?

- A new Paste and Go context menu option in the address bar, implemented by Iulian. It’s so simple, but it’s also the greatest thing ever. Why did nobody implement this earlier?

- A new Duplicate Tab context menu option on tabs, implemented by Gabriel. It’s not something I use myself, but it seems some folks who use it in other browsers were disappointed it was missing in Epiphany.

- A new keyboard shortcuts dialog is available in the app menu, implemented by Gabriel.

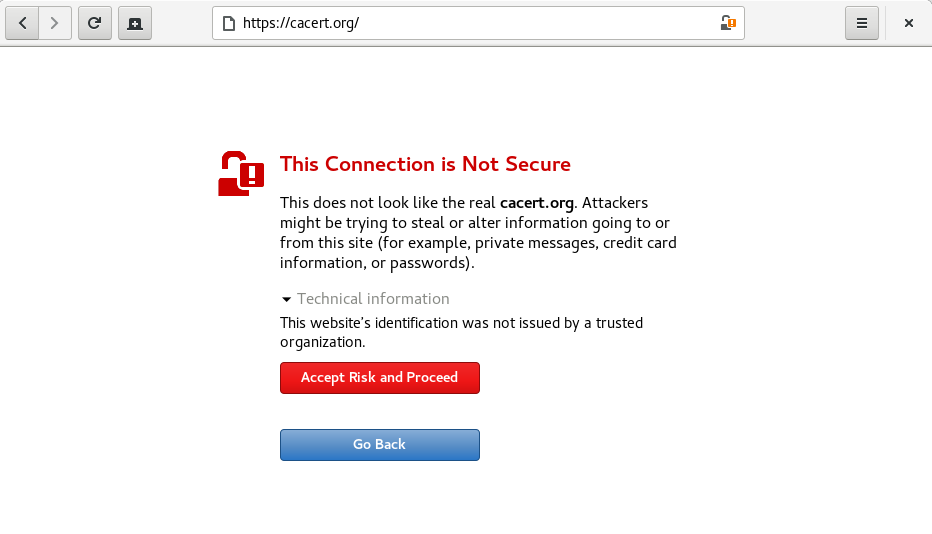

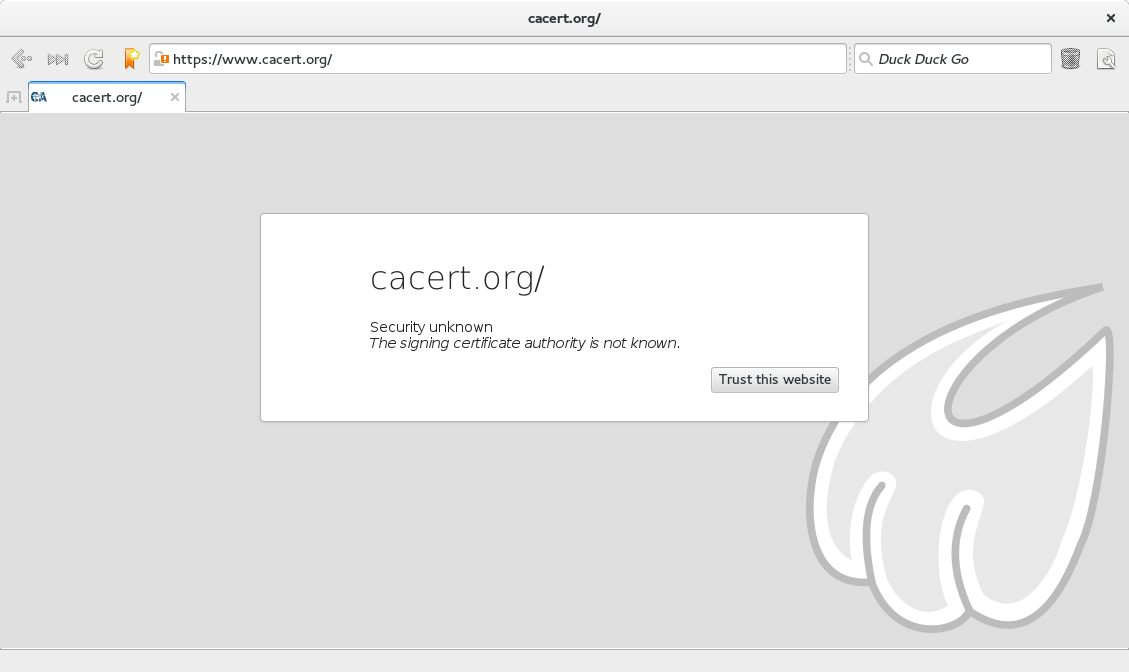

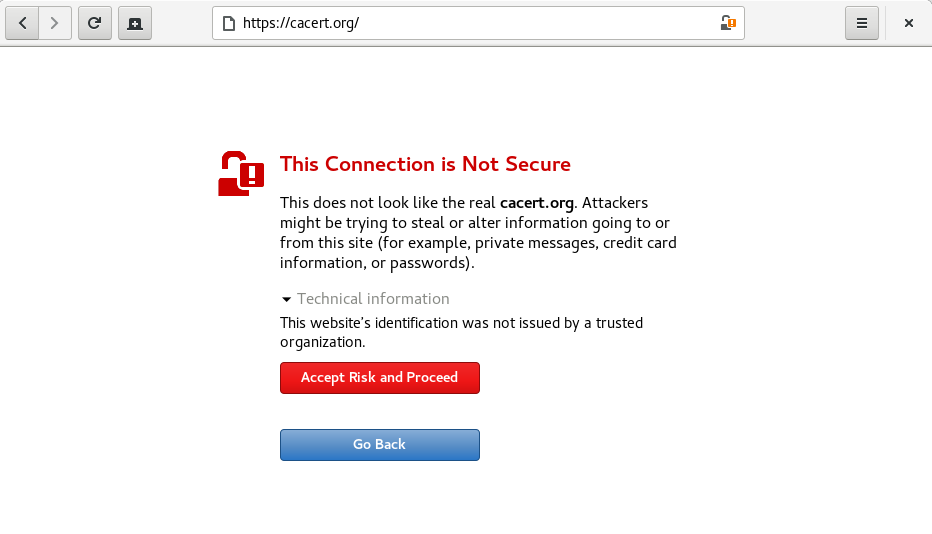

Gabriel also redesigned all the error pages. My favorite one is the new TLS error page, based on a mockup from Jakub Steiner:

Web app improvements

Pivoting to web apps, Daniel Aleksandersen turned his attention to the algorithm we use to pick a desktop icon for newly-created web apps. It was, to say the least, subpar; in Epiphany 3.20, it normally always fell back to using the website’s 16×16 favicon, which doesn’t look so great in a desktop environment where all app icons are expected to be at least 256×256. Epiphany 3.22 will try to pick better icons when websites make it possible. Read more on Daniel’s blog, which goes into detail on how to pick good web app icons.

Also new is support for system-installed web apps. Previously, Epiphany could only handle web apps installed in home directories, which meant it was impossible to package a web app in an RPM or Debian package. That limitation has now been removed. (Update: I had forgotten that limitation was actually removed for GNOME 3.20, but the web apps only worked when running in GNOME and not in other desktops, so it wasn’t really usable. That’s fixed now in 3.22.) This was needed to support packaging Fedora Developer Portal, but of course it can be used to package up any website. It’s probably only interesting to distributions that ship Epiphany by default, though. (Epiphany is installed by default in Fedora Workstation as it’s needed by GNOME Software to run web apps, it’s just hidden from the shell overview unless you “install” it.) At least one media outlet has amusingly reported this as Epiphany attempting to compete generally with Electron, something I did write in a commit message, but which is only true in the specific case where you need to just show a website with absolutely no changes in the GNOME desktop. So if you were expecting to see Visual Studio running in Epiphany: haha, no.

Shortcut woes

On another note, I’m pleased to announce that we managed to accidentally stomp on both shortcuts for opening the GTK+ inspector this cycle, by mapping Duplicate Tab to Ctrl+Shift+D, and by adding a new Ctrl+Shift+I shortcut to open the WebKit web inspector (in addition to F12). Go team! We caught the problem with Ctrl+Shift+D and removed the shortcut in time for the release, so at least you can still use that to open the GTK+ inspector, but I didn’t notice the issue with the web inspector until it was too late, and Ctrl+Shift+I will no longer work as expected in GTK+ apps. Suggestions welcome for whether we should leave the clashing Ctrl+Shift+I shortcut or get rid of it. I am leaning towards removing it, because we normally match Epiphany behavior with GTK+, and only match other browsers when it doesn’t conflict with GTK+. That’s called desktop integration, and it’s worked well for us so far. But a case can be made for matching other browsers, too.

Stable releases

On top of Epiphany 3.22, I’ve also rolled new stable releases 3.20.4 and 3.18.8. I don’t normally blog about stable releases since they only include bugfixes and are usually boring, so why are these worth mentioning here? Two reasons. First, one of the fixes in these releases is quite significant: I discovered that a few important features were broken when multiple tabs share the same web process behind the scenes (a somewhat unusual condition): the load anyway button on the unacceptable TLS certificate error page, password storage with GNOME keyring, removing pages from the new tab overview, and deleting web applications. It was one subtle bug that was to blame for breaking all of those features in this odd corner case, which finally explains some difficult-to-reproduce complaints we’d been getting, so it’s good to put out that bug of the way. Of course, that’s also fixed in Epiphany 3.22, but new stable releases ensure users don’t need a full distribution upgrade to pick up a simple bugfix.

Additionally, the new stable releases are compatible with WebKitGTK+ 2.14 (to be released later this week). The Epiphany 3.20.4 and 3.18.8 releases will intentionally no longer build with older versions of WebKitGTK+, as new WebKitGTK+ releases are important and all distributions must upgrade. But wait, if WebKitGTK+ is kept API and ABI stable in order to encourage distributions to release updates, then why is the new release incompatible with older versions of Epiphany? Well, in addition to stable API, there’s also an unstable DOM API that changes willy-nilly without any soname bumps; we don’t normally notice when it changes, since it’s autogenerated from web IDL files. Sounds terrible, right? In practice, no application has (to my knowledge) ever been affected by an unstable DOM API break before now, but that has changed with WebKitGTK+ 2.14, and an Epiphany update is required. Most applications don’t have to worry about this, though; the unstable API is totally undocumented and not available unless you #define a macro to make it visible, so applications that use it know to expect breakage. But unannounced ABI changes without soname bumps are obviously a big a problem for distributions, which is why we’re fixing this problem once and for all in WebKitGTK+ 2.16. Look out for a future blog post about that, probably from Carlos Garcia.

elementary OS

Lastly, I’m pleased to note that elementary OS Loki is out now. elementary is kinda (totally) competing with us GNOME folks, but it’s cool too, and the default browser has changed from Midori to Epiphany in this release due to unfixed security problems with Midori. They’ve shipped Epiphany 3.18.5, so if there are any elementary fans in the audience, it’s worth asking them to upgrade to 3.18.8. elementary does have some downstream patches to improve desktop integration with their OS — notably, they’ve jumped ahead of us in bringing back the traditional address bar — but desktop integration is kinda the whole point of Epiphany, so I can’t complain. Check it out! (But be sure to complain if they are not releasing WebKit security updates when advised to do so.)