Multi-monitor has come up a fair bit in conversations about the GNOME Shell UX updates that are coming in GNOME 40. There’s been some uncertainty and anxiety in this area, so we wanted to provide more detail on what the multi-monitor experience will exactly be like, so people know what to expect. We also wanted to provide background on the decisions that have been made.

Newsflash

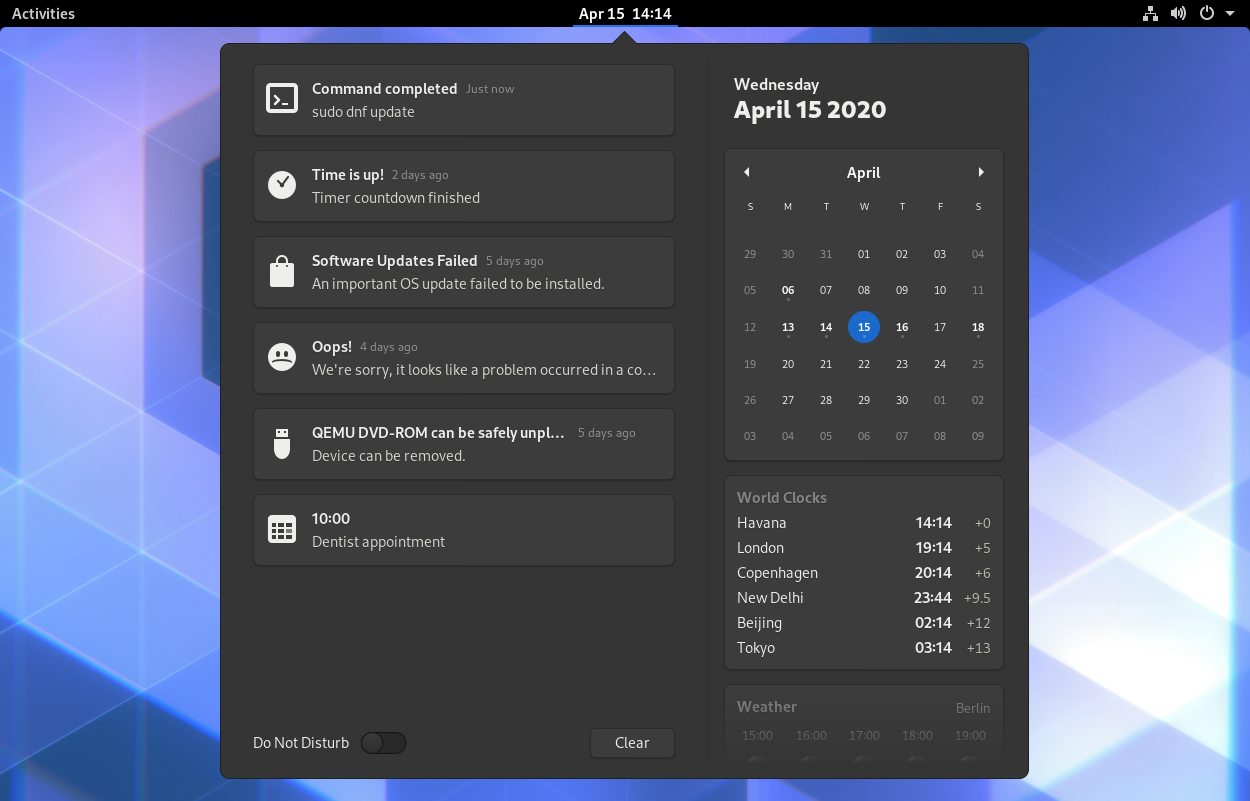

Before we get into multi-monitor, a short status update! As you would expect for this stage in the development cycle, the main bulk of the UI changes are now in the GNOME Shell master branch. This was the result of a really hard push by Georges and Florian, so huge thanks to them! Anyone who is interested in following this work should ensure that they are running the master branch, and not the now redundant development branch.

There are still a few relatively minor UI changes that we are hoping to land this cycle, but overall the emphasis is now on stabilisation and bug fixing, so if you are testing and have spotted any issues, now’s the time to report them.

Multi-monitor

OK, back to multi-monitor!

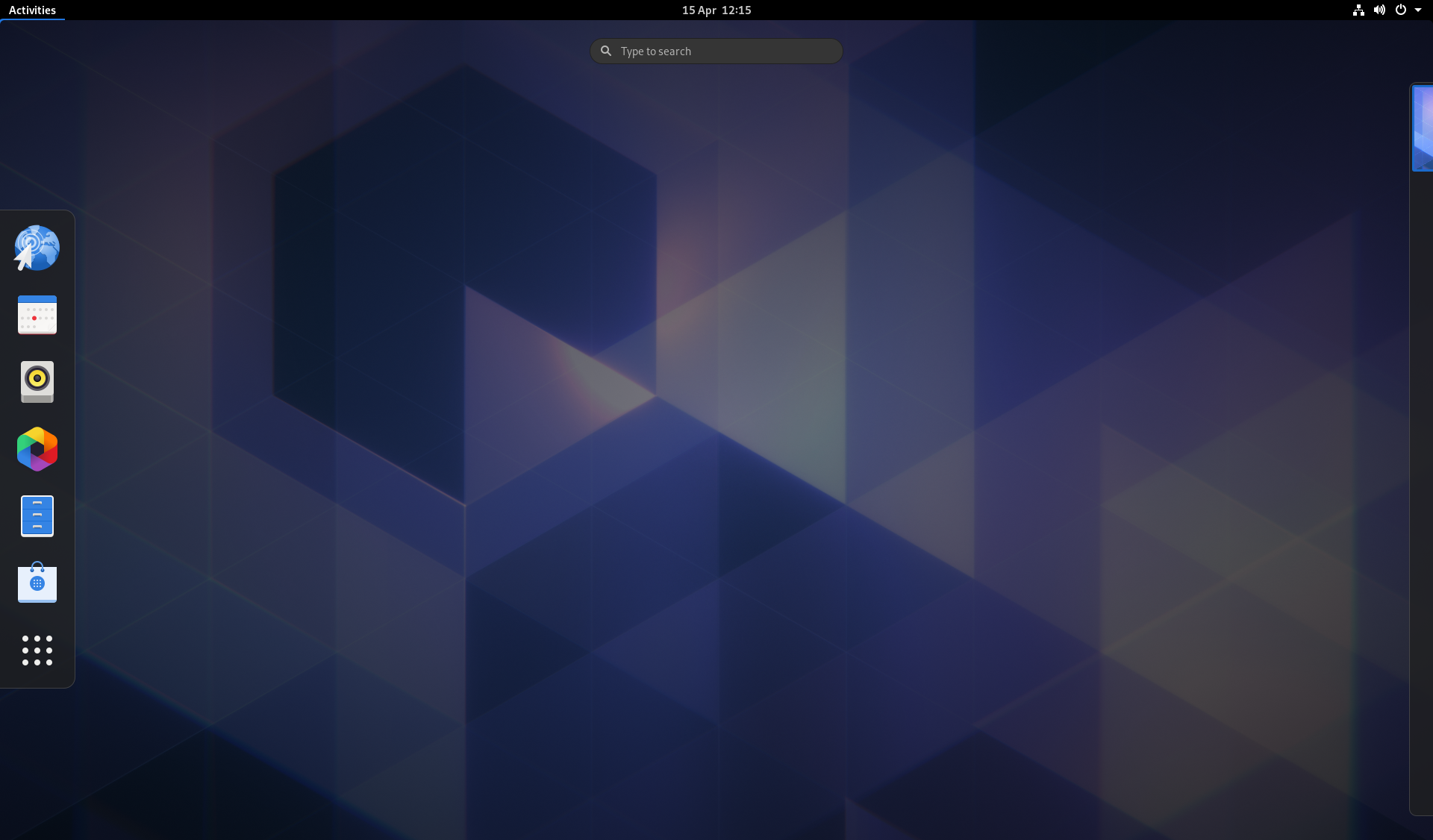

In many key respects, multi-monitor handling in GNOME 40 will be identical to how it is in 3.38. GNOME 40 still defaults to workspaces only on the primary display, as we have since 3.0. The top bar and overview will only be shown on the primary display, and the number of workspaces will still be dynamic. In many respects, GNOME 40 should feel very similar to previous GNOME versions, therefore.

That still leaves a lot of unanswered questions, of course, so let’s run through the GNOME 40 multi-monitor experience in more detail. Much of this concerns how workspaces will work in combination with multi-monitor setups.

Default configuration

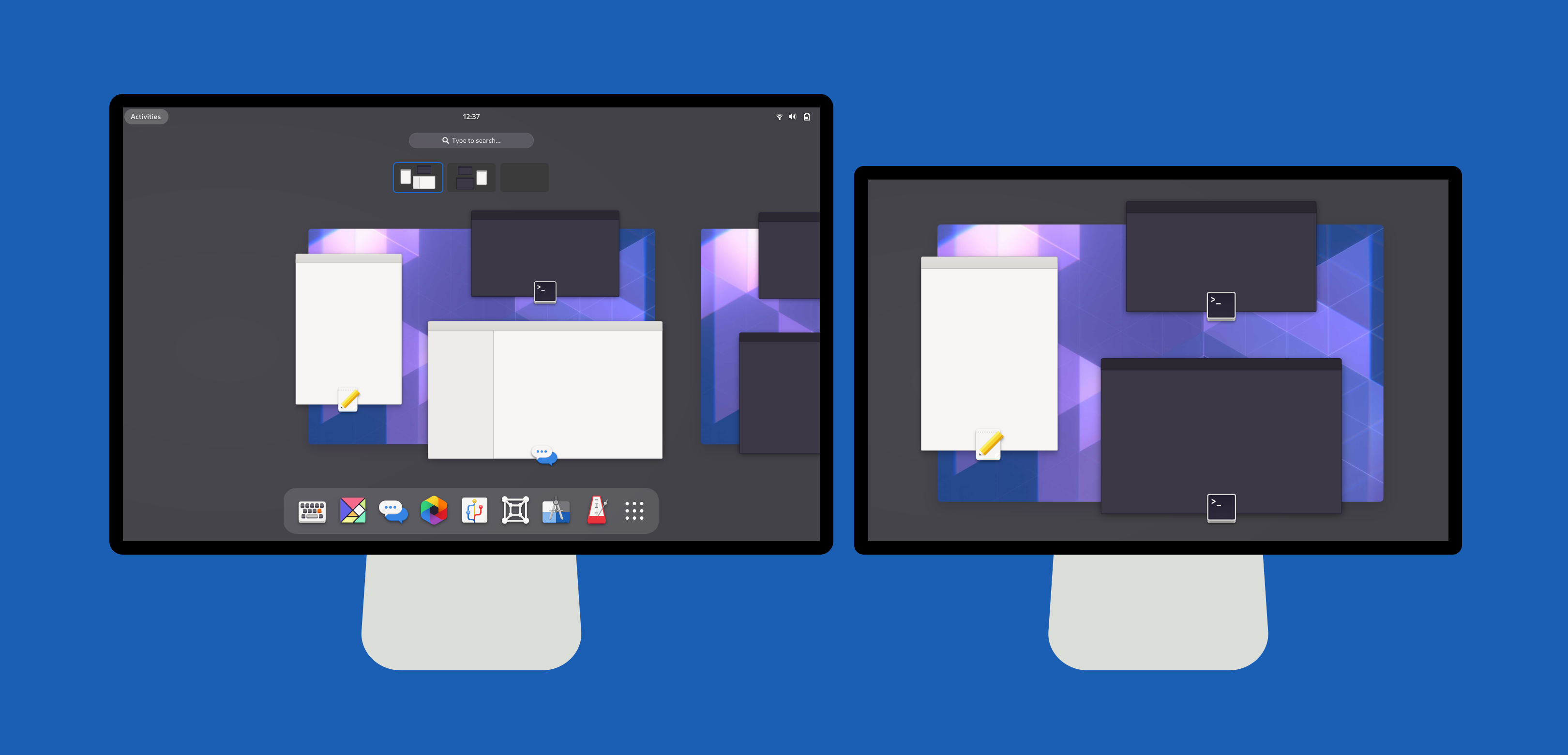

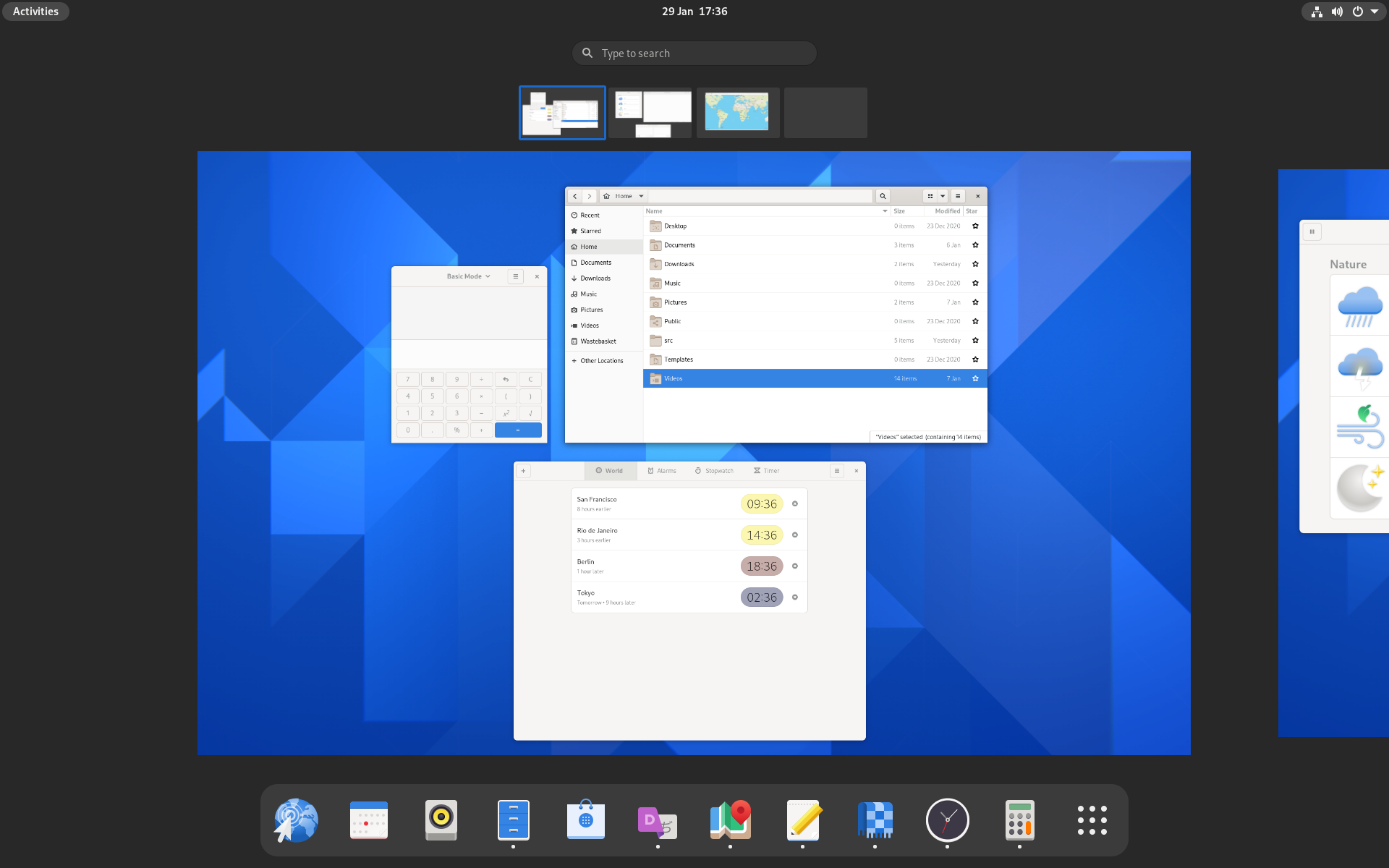

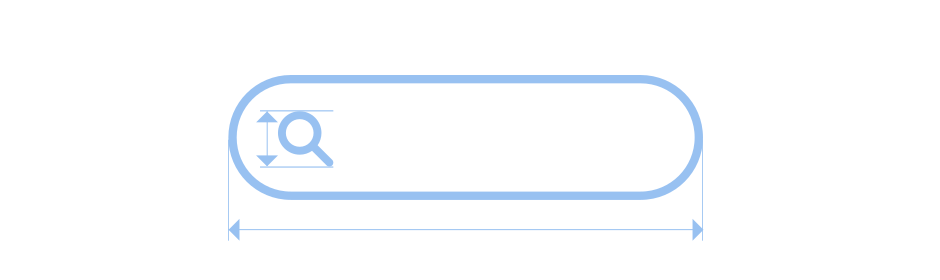

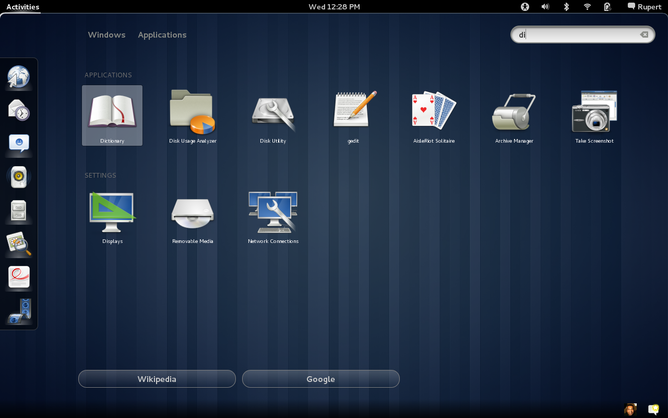

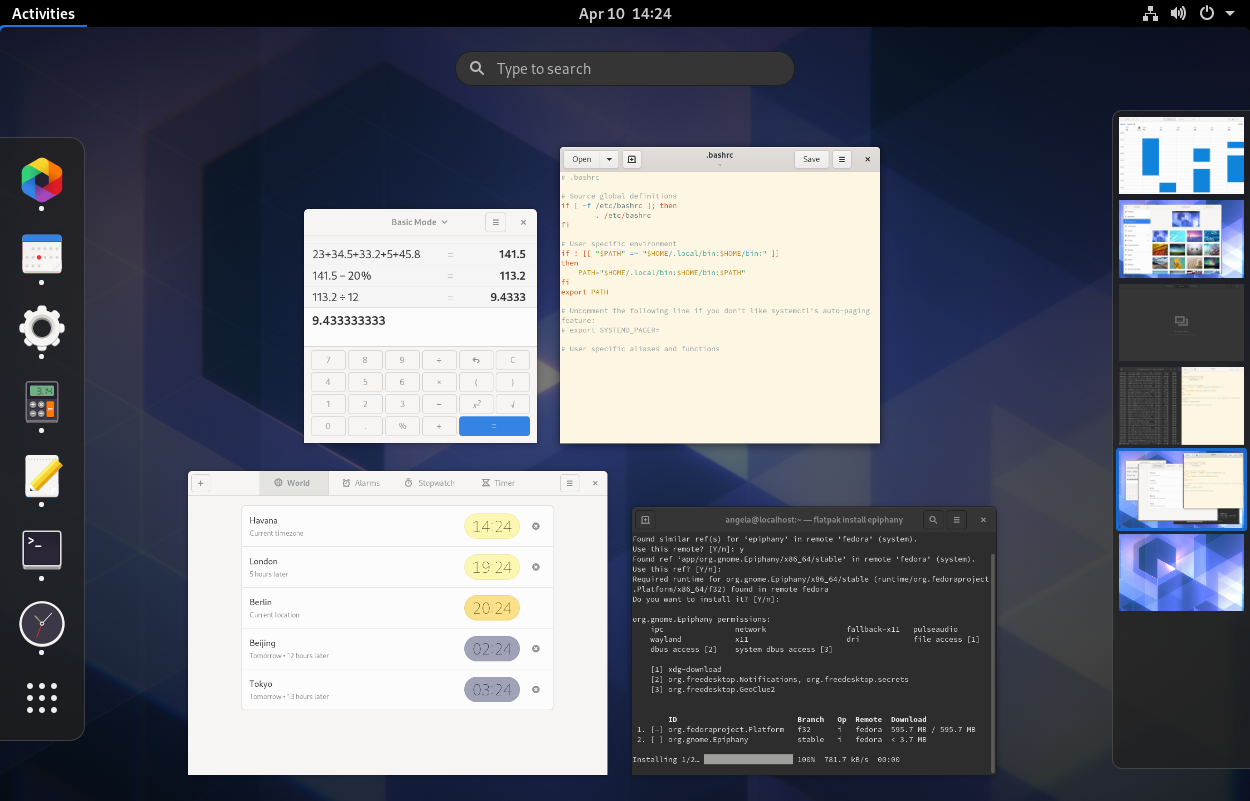

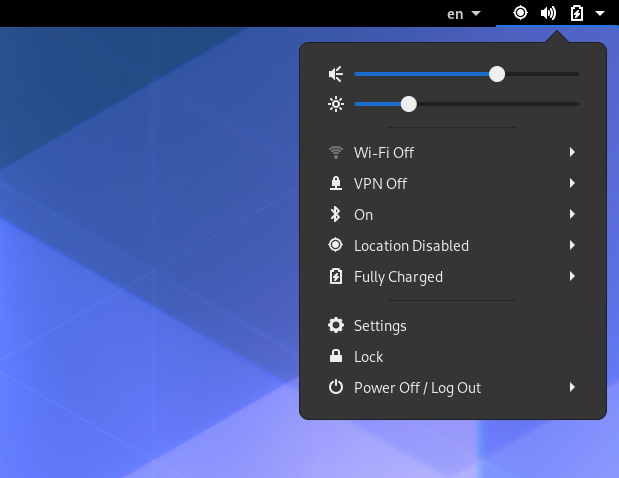

As mentioned already, GNOME 40 will continue to default to only showing workspaces on the primary display. With a dual display setup, the overview will therefore look like this by default:

One detail to notice is how we’re scaling down the background on the secondary display, to communicate that it’s a single workspace like those on the primary display. We feel that this presentation helps to make the logic of the multiple displays clearer, and helps to unify the different screens.

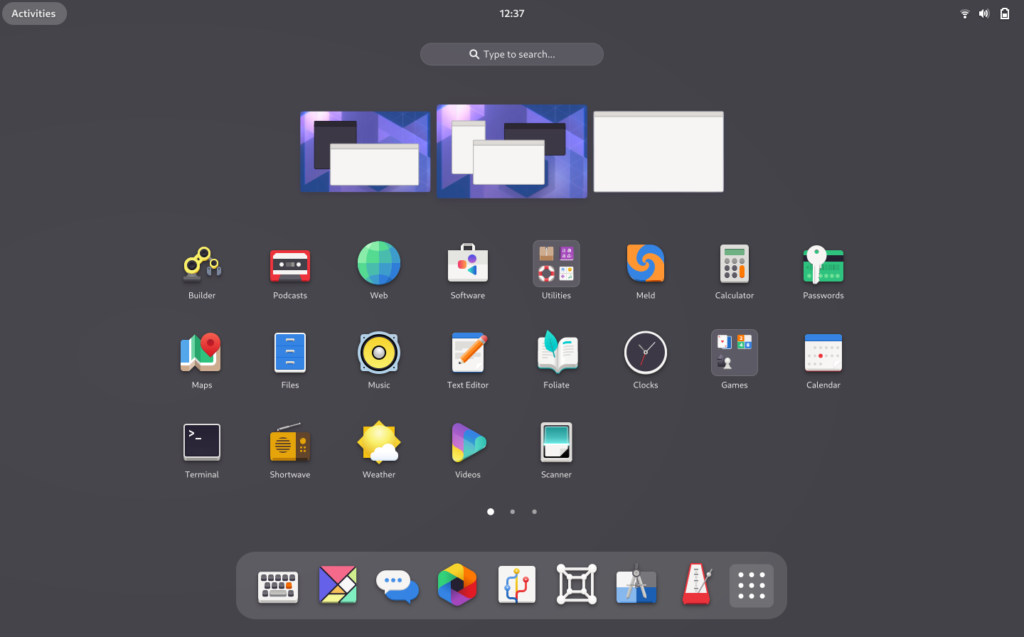

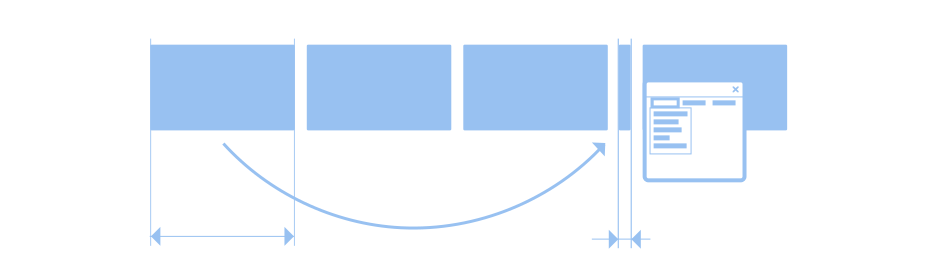

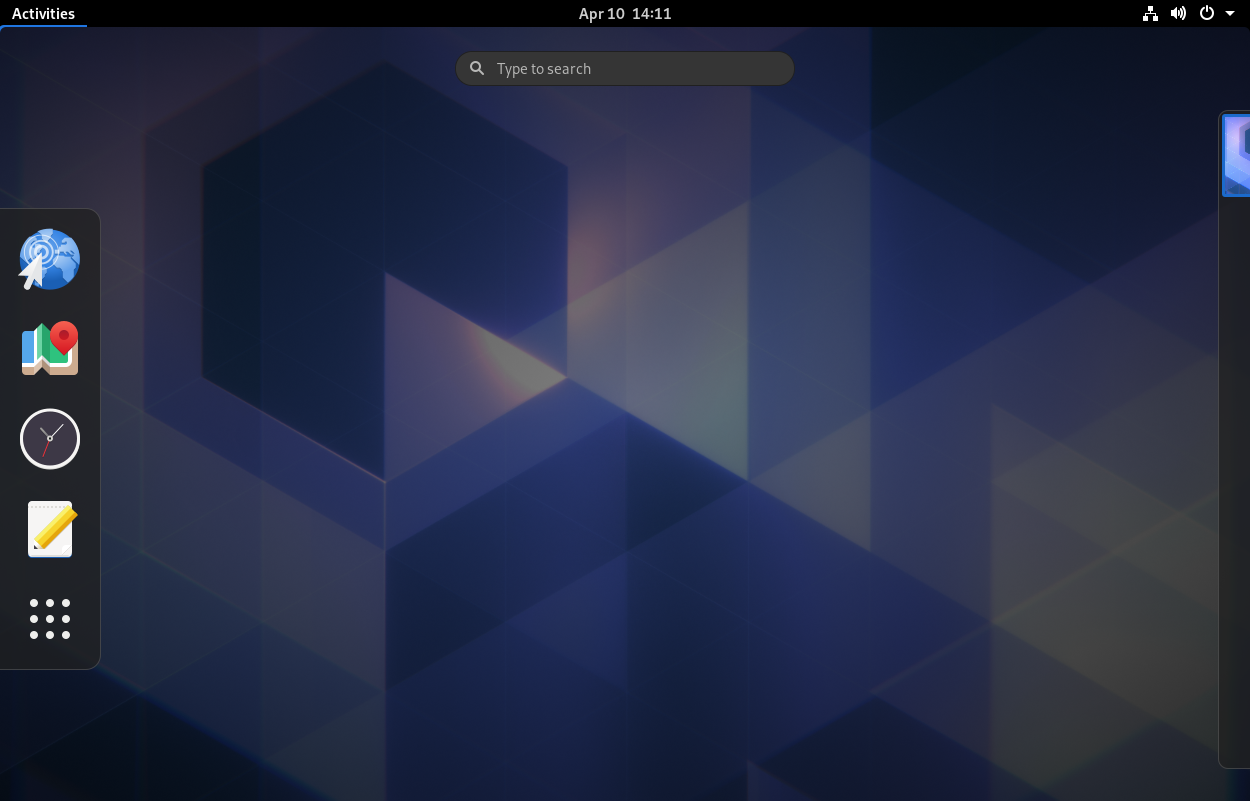

To get an idea of what this will look like in use, Jakub Steiner has kindly created some motion mockups. These are intended to communicate how each part fits together and what the transitions will be like, rather than being a 100% accurate rendering of the final product (in particular, the transitions have been slowed down).

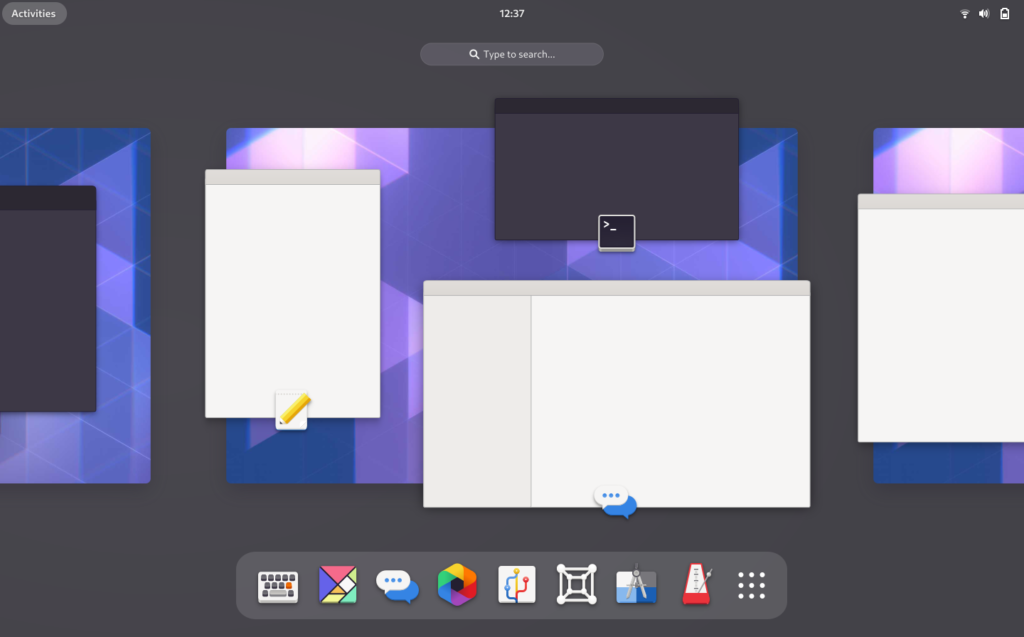

Here you can get an idea of what it will look like opening the overview and moving between workspaces. Just like the current default configuration, workspace switching only happens on the primary display.

Workspaces on all displays

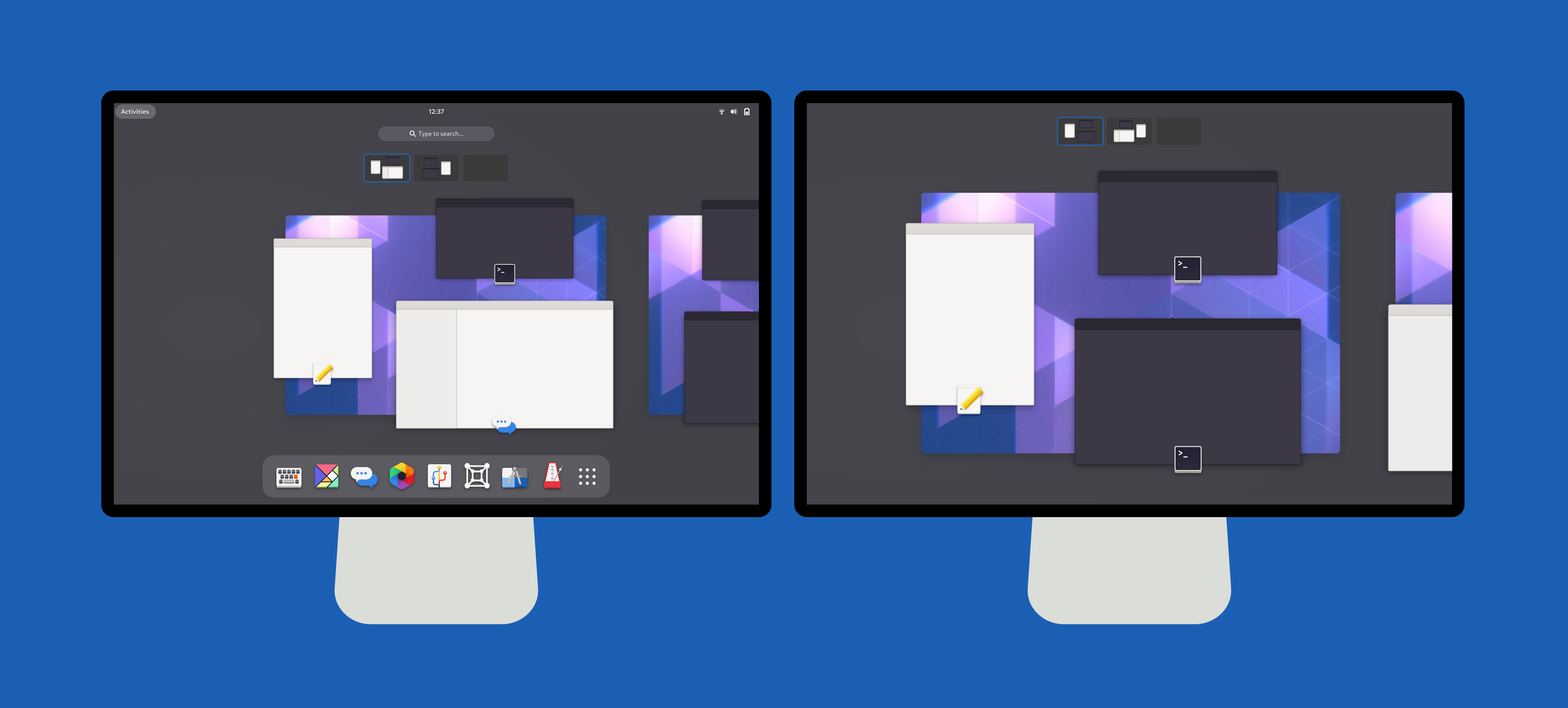

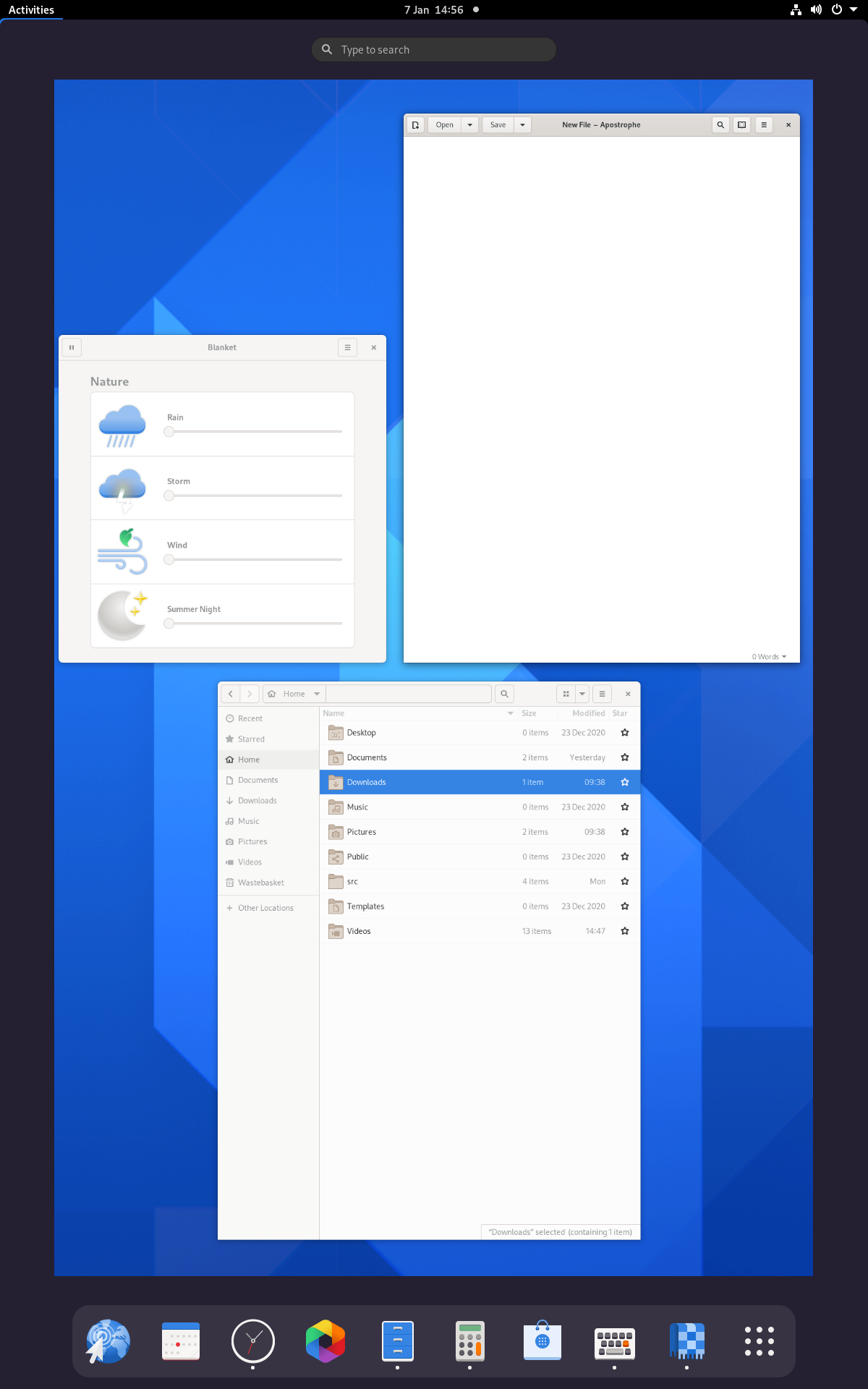

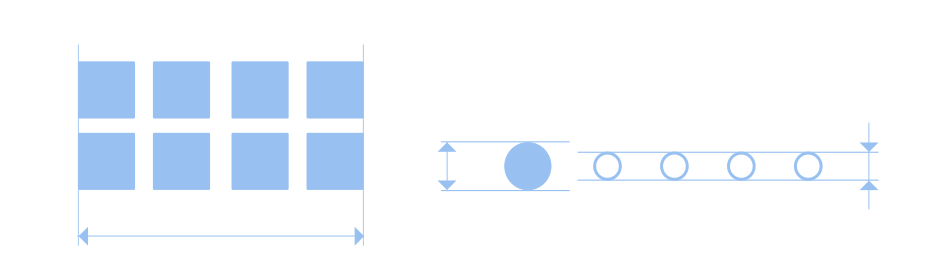

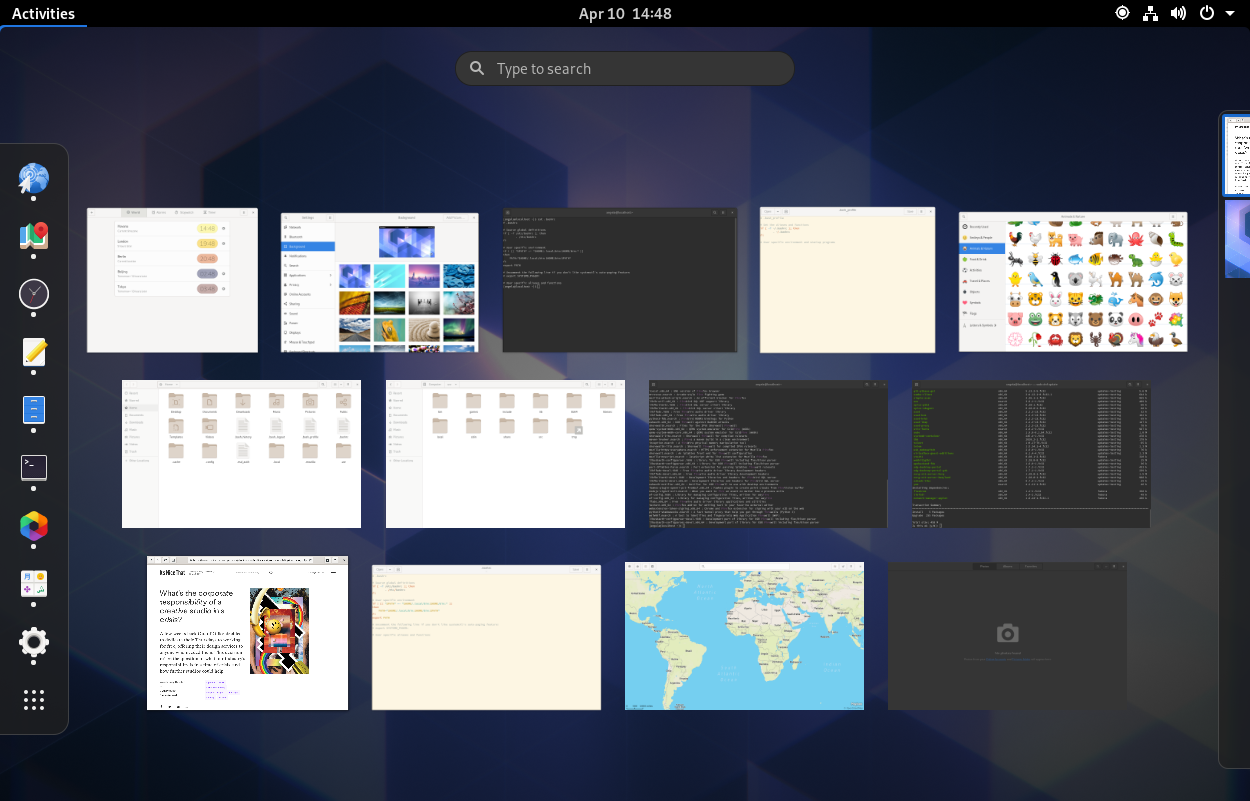

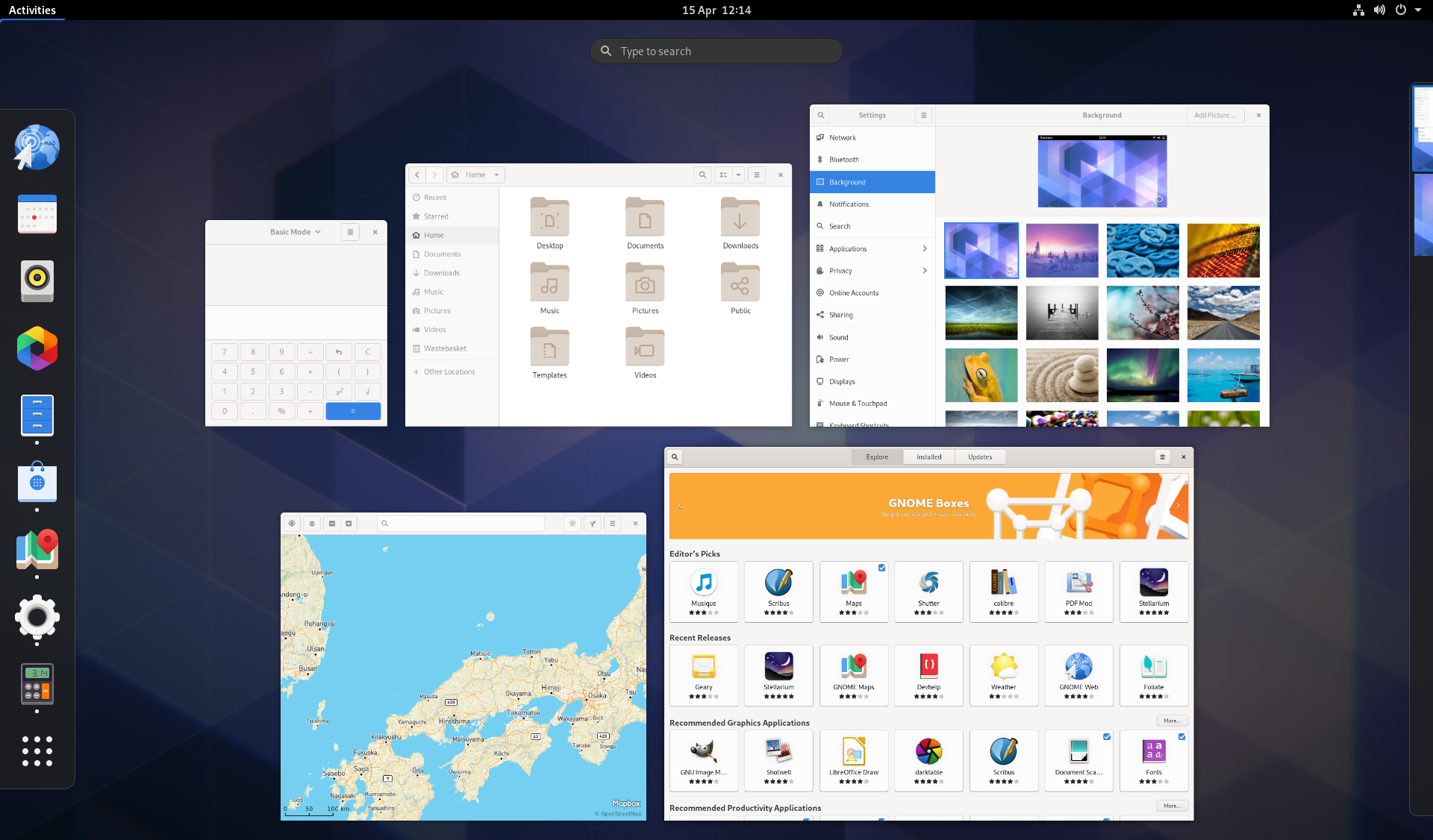

While workspaces only being on the primary display is the default behaviour, GNOME also supports having workspaces on all displays, using the workspaces-only-on-primary settings key. The following static mockup shows what the overview will look like in GNOME 40 with this configuration.

As you can see, this is very similar to the workspaces only on primary configuration. The main difference is that you can see the additional workspaces extending to the right on the secondary display. It’s also possible to see that the workspace navigator (the small set of thumbnails at the top) is visible on both displays. The introduction of the workspace navigator on secondary displays is a new change for GNOME 40, which is intended to improve the experience for users who opt to have workspaces on all displays. We know from our user research that this is something that many users will welcome.

Like in other GNOME versions, when workspaces are on all displays, they are switched in unison. For example, all displays show workspace 2 at the same time. This can be seen in the motion mockups:

Keyboard shortcuts

The existing workspace shortcuts will continue to work in GNOME 40. Super+PgUp/PgDown will continue to switch workspace. Adding Shift will continue to move windows between workspaces.

We are also introducing additional shortcuts which align with the horizontal layout. The new shortcut to switch workspace will be Super+Alt+←/→. Moving windows between workspaces will be Super+Alt+Shift+←/→. Super+Alt+↑ will also open the overview and then app grid, and Super+Alt+↓ will close them.

These directional keyboard shortcuts have matching touchpad gestures: three-finger swipes left and right will switch workspaces, and three-finger swipes up and down will open the overview and app grid.

Why horizontal?

A few people have pointed out that horizontal workspaces aren’t as clean with horizontal multi-monitor setups. The concern is that, when multiple displays are horizontal, they end up clashing with the layout of the workspaces. There is some truth in that, and we recognise that some users might need to adjust to this aspect of the design.

However, it’s worth pointing out that horizontal workspaces are a feature of every other desktop out there. Not only is it how every other desktop does it, but it is also how GNOME used to do it prior to 3.0, and how GNOME’s classic mode continues to do it. Therefore, we feel that horizontal workspaces and horizontally-arranged displays can get along just fine. If anyone is concerned about this, we’d suggest that you give it a try and see how it goes.

Some people have also asked why we are making the switch to horizontal workspaces at all, which is fair! Here I think that it needs to be understood that horizontal workspaces are fundamental to the the design we’re pursuing for 40: the film-strip of workspaces (which proved effective in testing), the clearer organisation of the overview, the coherent touchpad gestures, a dash that can more comfortably scale to include more items, and so on. This is all facilitated by the workspace orientation change, and would not be possible without it.

GNOME ❤️ multi-monitor

In case there’s any doubt: multi-monitor is absolutely a priority for us in the shell design and development team. We know that the multi-monitor experience is important to many GNOME users (including many of us who work on GNOME!), and it is something that we’re committed to improving. This applies to both the default workspaces behaviour as well as the workspaces on all displays option.

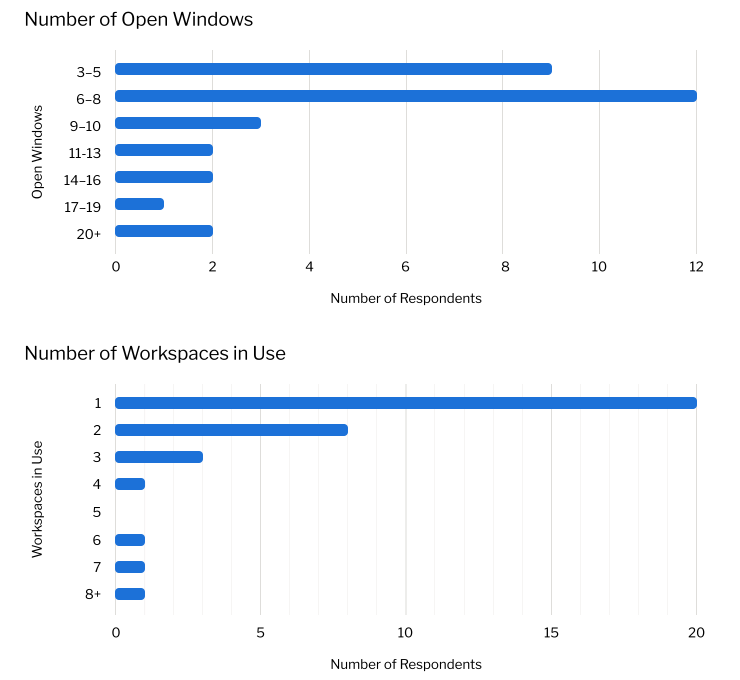

Multi-monitor considerations regularly featured in the design planning for GNOME 40. They were also a research theme, both in our early discovery interviews and survey, as well as in the diary study that we ran. As a result of this, we are confident that GNOME 40 will provide an excellent multi-monitor experience.

We actually have a few plans for multi-monitor improvements in the future. Some of these pre-date the GNOME 40 work that is currently happening, and we hope to get back to them during the next development cycle. Our ambition is for the multi-monitor story to keep on getting better.

Thanks for reading!