This cycle GTK got a lot of updates to its CSS engine.

I started this work as part of the Sovereign Tech Fund initiative, and later on Matthias Clasen joined in and we ended up splitting the work on colors.

Let’s go through the changes, as well as how they affect GTK, libadwaita and apps.

Variables

The most notable addition is CSS variables, more correctly known as custom properties.

Since before GTK switched to CSS for styles, it has had named colors, a non-standard addition providing a similar functionality. You could define a color, then refer to it by name. Unfortunately, they had big limitations. First, they are global. You can only define colors for the whole stylesheet, and if you want to override them for a single widget subtree – you’re out of luck. Second, they were obviously only for colors.

The only option to have them local to a widget was to use gtk_style_context_add_provider() on a GtkStyleContext obtained via gtk_widget_get_style_context. However, it had an even bigger problem: being local to a widget, it didn’t propagate to children, which made it practically useless. Even for widgets that seemingly don’t have children: for example, if you add a provider to a GtkEntry, it won’t affect its text, or the icons, or the progress bar – they are all separate widgets within the entry. So, it shouldn’t be a big surprise that this API is deprecated.

Variables, meanwhile, don’t have any of these limitations. They can be defined anywhere, propagate to children, and they can be anything – colors, numbers, dimensions, etc. For example, we can override them for a specific widget as follows:

:root {

--some-color: red;

}

my-widget {

--some-color: green;

}

After defining, they can be accessed with the var() function:

my-widget {

color: var(--some-color);

}

This function also allows to specify a fallback in case a variable doesn’t exist, as follows:

my-widget {

color: var(--some-color, var(--some-other-color, red));

}

Here it will try, in order, --some-color, then --some-other-color, and if neither exists, red.

The standard place to declare global variables is the :root selector, and so it’s now supported too. While GTK root widgets usually have the window selector, that’s not always the case. For example, GtkCheckButton within a GtkTreeView are their own toplevels and targeting window would not include them. While tree view is deprecated and hopefully on its way out, we have to support it anyway for now, and who knows what other root widgets appear in future, and having :root solves it all nicely.

Variables can even be animated, though that’s not particularly useful: since they can be anything and you may potentially be animating red into 2px, the only way to interpolate them is to have a jump from the initial value to final value at 50%. Either way, the spec allows that and we implement it. You can still use them within another property’s value and animate that property instead – that will work as expected.

There are some things we don’t support at the moment, like the @property at-rule. It allows to declare variable types, optionally prevent inheriting, and specify the default value. Having a type not only provides type checking (and hence more informative error messages), but also allows to actually interpolate variables in animations. See, if a variable can be anything, we can’t interpolate it other than with a jump in the middle. But if we can guarantee it’s a color, or a dimension, or a number, or whatever, at every keyframe, then we can. But, while that would be neat to have, it’s really niche compared to having variables themselves, and so not very important.

Another thing is that it’s not possible to use variables within named colors, like this:

@define-color my_color var(--something); /* this is an error */

Since named colors will be going away in future, that’s not a big deal, but it is worth mentioning anyway. The other way around does work though:

@define-color something red;

:root {

--my-color: @something; /* this is perfectly fine */

}

(and that’s fairly important, as it allows us to switch to variables without breaking backwards compatibility)

Colors

Next, colors. A lot of features from CSS Color Module Level 4 and Level 5 were implemented as well.

Modern syntax

In the past, CSS has used the following syntax for defining colors:

rgb(255, 0, 0)

rgba(255, 0, 0, 0.5)

hsl(0, 100%, 50%)

hsla(0, 100%, 50%, 0.5)

That’s still supported, but modern CSS also has a simpler and more flexible syntax:

rgb(255 0 0)

rgb(255 0 0 / 50%)

hsl(0 100 50)

hsl(0 100 50 / 50%)

It allows to freely mix percentages and numbers, and makes alpha an optional parameter separated by solidus instead of having separate functions. And now GTK supports it too.

Modern syntax also supports specifying missing components, for example: hsl(none 100% 50%). In most situations they behave same as 0, but they make a difference for interpolation, so we’ll talk about that in more details later.

Additionally, it supports specifying hue in hsl() as an angle instead of a number (meaning that it’s possible to use units like turn instead of degrees), as well as calc() anywhere within these functions:

hsl(calc(0.5turn - 10deg) 100% 50% / calc(1 / 2))

More color spaces

GTK also supports a bunch more color spaces now, all using the modern syntax:

| Color space |

CSS |

| Linear sRGB |

color(srgb-linear 1 0 0) |

| HWB |

hwb(0deg 0 0) |

| Oklab |

oklab(62.8% 0.22 0.13) |

| Oklch |

oklch(62.8% 0.25 29) |

I won’t be describing the color spaces in detail, but that information can be easily found online. For example, Oklab and Oklch are very well described in their creator’s blog post.

color() also supports sRGB, but it works same as rgb(), except the channels have 0-1 range instead of 0-255.

color() in the spec supports a lot more color spaces, for example Display P3, but since we don’t have HDR support in GTK just yet, supporting them wouldn’t be of much use at the moment, so that’s omitted. Also omitted are Lab, LCh and various XYZ color spaces for now. Oklab/Oklch work better than Lab/LCh for UI colors anyway, and XYZ is fairly niche and not widely used in this context.

However, just defining colors in different color spaces isn’t that interesting to me. What’s more interesting is deriving new colors from from existing ones in those color spaces, so let’s look at that.

Color mixing

First, we have support for the color-mix() function. While GTK has had a non-standard mix() function for more than a decade, color-mix() is not only standard CSS, but also a whole lot more flexible. Most important is the fact it allows to mix colors in different color spaces instead of just sRGB – all of the ones mentioned above:

color-mix(in oklch, red, green)

For HSL, HWB and Oklch, it’s possible to specify the hue interpolation mode too – for example, color-mix(in hsl longer hue, red, green).

color-mix() also allows more sophisticated mixing via missing components. They allow some channels to be taken from one of the colors without taking the other one into account at all. For example, the following mix:

color-mix(in srgb, rgb(100% none 100%), rgb(none 50% 0))

takes the red channel from the first color, the green channel from the second color, and mixes the blue channel from both colors, resulting in the following color: color(srgb 1 0.5 0.5).

For comparison, the same mix but with none replaced by 0:

color-mix(in srgb, rgb(100% 0 100%), rgb(0 50% 0))

mixes every channel and produces color(srgb 0.5 0.25 0.5).

While mix() specifies a single fraction for the mix, color-mix() specifies two percentages. Usually they are normalized so that they add up to 100%, but if their sum is lower than that, it’s used as an alpha multiplier, allowing to add transparency to the mix:

color-mix(in srgb, red 30%, blue 20%)

/* color(srgb 0.6 0 0.4 / 0.5) */

Percentages are optional though. When one is omitted, it’s assumed to be the other one subtracted from 100%. When both are omitted, they are assumed to be 50%/50%.

Relative colors

GTK now also supports relative colors. Unlike mixing, these take one color and change its individual channels. For example, we can create a complementary color by inverting the hue:

hsl(from var(--some-color) calc(h + 0.5turn) s l)

Change a color’s lightness to a given value:

oklab(from var(--some-color) 0.9 a b)

Or add transparency to a color, like the SASS transparentize() function:

rgb(from var(--some-color) r g b / calc(alpha - 25%))

Combined with calc() and variables, this is a very flexible system, and I’m really curious to see how it will get used in future.

Math functions

There’s also support for a lot of math functions:

min(), max(), clamp()round()rem()mod()sin(), cos(), tan(), asin(), acos(), atan(), atan2()pow(), sqrt(), hypot(), log(), exp()

abs(), sign()e, pi, infinity, NaN

They can also be used in calc(), of course. I already found an interesting use case for two of them in libadwaita.

Misc changes

The opacity property can now accept percentages in addition to numbers. This wouldn’t matter much, but it means it can accept the same values as color-mix().

Now let’s look at other changes all of this allowed.

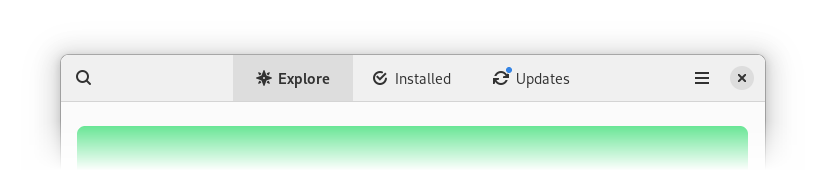

GTK deprecations

GTK has a bunch of non-standard additions to CSS, related to colors: most notably, @define-color and named colors, but also the alpha(), mix(), shade(), lighter() and darker() functions. They allow to manipulate colors. Some are more useful than others, but, for example, alpha() is used extensively in libadwaita and modern GNOME apps – especially in combination with currentColor. For example, libadwaita buttons have the following background color: alpha(currentColor, 0.1); and can work with both light and dark background – they just follow the text color.

As useful as they are, CSS now has standard ways to replace every single one of them, and apps are encouraged to do so.

Named colors

@define-color and named colors can be replaced with variables. For example, this snippet:

@define-color my_color red;

my-widget {

color: @my_color;

}

becomes:

:root {

--my-color: red;

}

my-widget {

color: var(--my-color);

}

mix()

This is straightforward. color-mix() works exactly same when using the sRGB color space.

/* mix(red, blue, .3) */

color-mix(in srgb, red 30%, blue)

alpha()

There are multiple ways to replace it. Both color-mix() and relative colors will do the job:

/* alpha(currentColor, 0.15); */

color-mix(in srgb, currentColor 15%, transparent)

rgb(from currentColor r g b / calc(alpha * 0.15))

Note that only the latter works for factors larger than 1.

alpha() is also often used with hardcoded colors, usually black. In that case just defining the color as is is sufficient:

/* alpha(black, .8) */

rgb(0 0 0 / 80%)

shade()

Shading is less obvious. One might assume that it would work same as mixing with black or white color, but… not quite. It was converting the colors to HSL, multiplying lightness and saturation, and converting back to sRGB. As such, mixing wouldn’t exactly work here, it will produce close but subtly different results, even when done in the HSL color space. For some color/factor combinations it would be same, but other times it will be different.

Relative colors, meanwhile, allow to manipulate each channel separately, and together with calc() we can do exactly same thing:

/* shade(red, 1.1) */

hsl(from red h calc(s * 1.1) calc(l * 1.1))

This is a lot more verbose, but it produces the same result as shade() for any color and factor. Of course, one could go further and use color spaces like Oklch or Oklab instead, and have more consistent results due to their perceptual nature. More on that later.

lighter() and darker()

Well, these are simple. They are just shade() with hardcoded factor parameter: 1.3 for lighter() and 0.7 for darker(). As such, they are replaced the same way:

/* lighter(red) */

hsl(from red h calc(s * 1.3) calc(l * 1.3))

/* darker(red) */

hsl(from red h calc(s * 0.7) calc(l * 0.7))

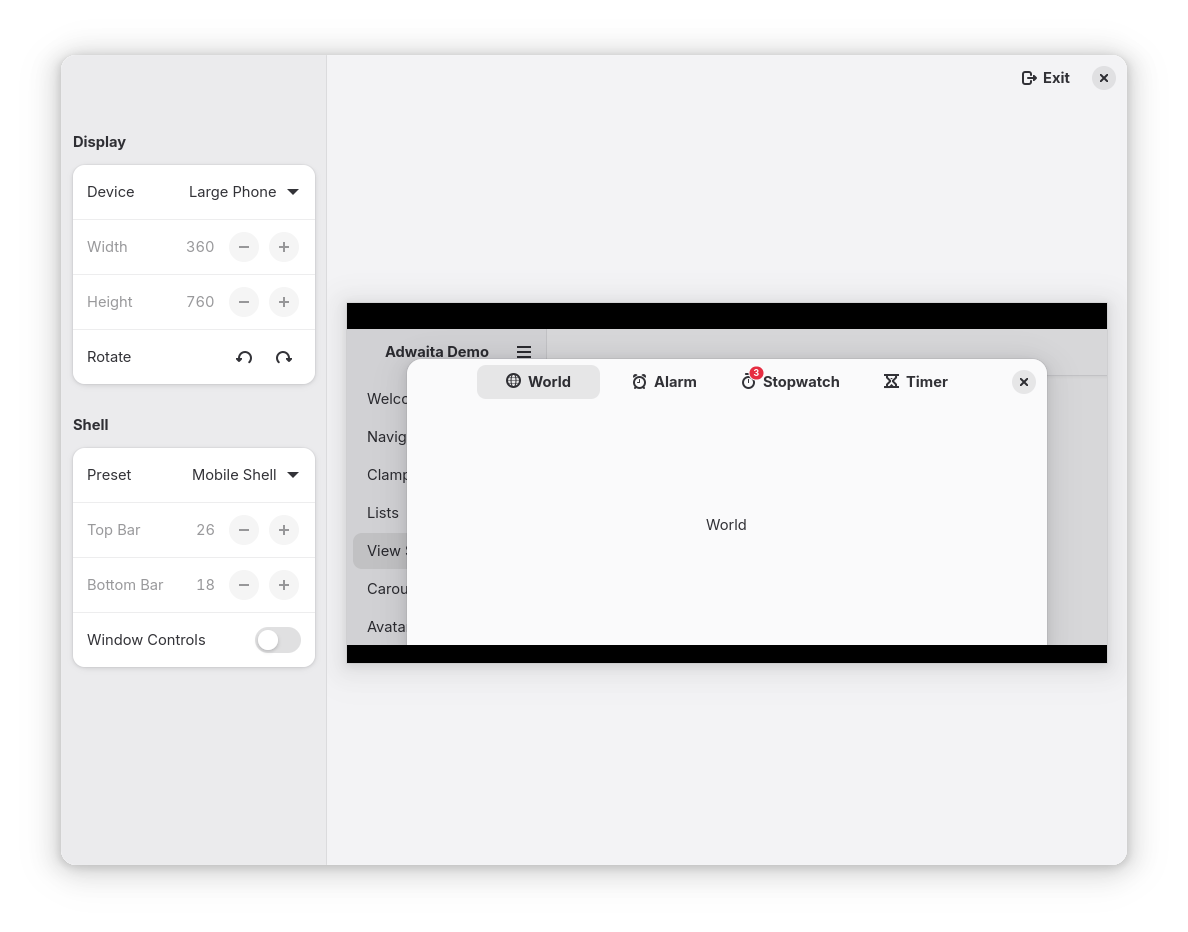

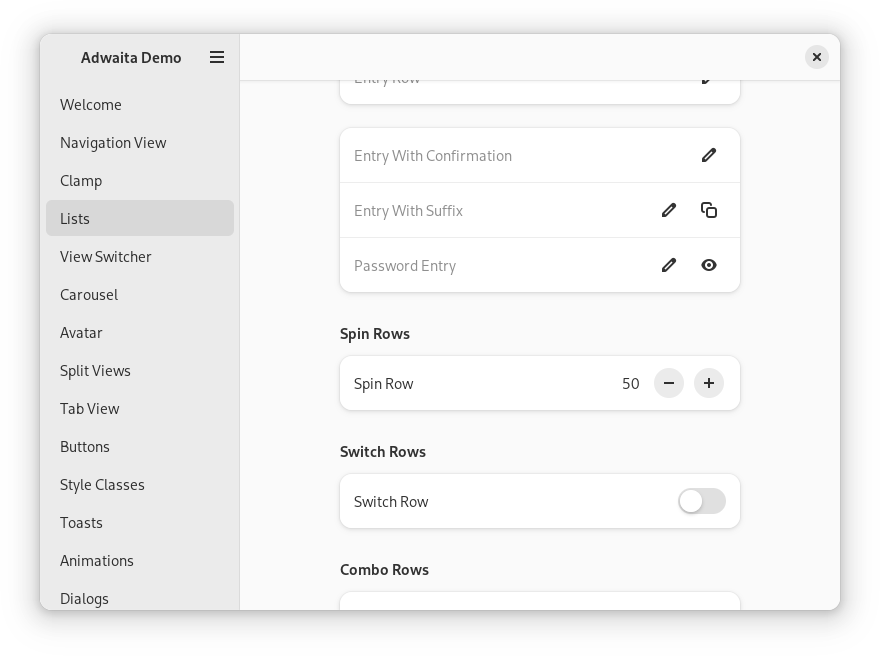

Libadwaita changes

This has allowed to clean up a lot of things in libadwaita styles too.

Named colors?

First of all, all of the existing named colors are available as variables too now. For backwards compatibility reasons their defaut values reference the old colors, for example:

:root {

--window-bg-color: @window_bg_color;

--window-fg-color: @window_fg_color;

}

They are named the same way as for the old colors, but with dashes in the names instead of underscores. One exception is that @borders became --border-color instead, for consistency with other colors.

However, being variables they can still be overridden per widget, have fallbacks and so on.

NOTE: since they reference named colors, using these variables will produce deprecation warnings with GTK_DEBUG=css. This is a known issue, but there isn’t much that can be done here, other than breaking compatibility for all existing apps with custom styles.

Also, overriding these variables won’t affect styles that use the old named colors directly. This isn’t a big issue if you’re porting your app (because you can replace both definitions and mentions at once), but may be a problem with libraries like libpanel which provide their own styles and use a lot of named colors. Once those libraries are ported though, it will work fine for both apps that have and haven’t been updated.

All of the available CSS variables are documented on their page, just like the old named colors. If you’re using libadwaita 1.5 or below, the old docs are still where they were.

It should be noted that compability colors like @theme_bg_color don’t have equivalent variables. Those colors only exist for compatibility, and apps using libadwaita shouldn’t be using them in the first place – specifically that color can be replaced by --window-bg-color, and so on. This can be a problem for libraries like WebKitGTK, however, so maybe there should be an agreed upon set of variables too. For now though, named colors still exist and won’t go away until GTK5, but this is something that needs be figured out at some point.

New variables

There are a few additions as well:

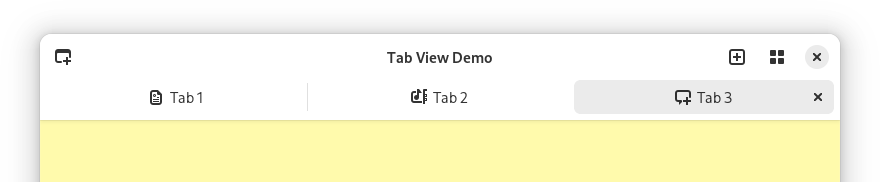

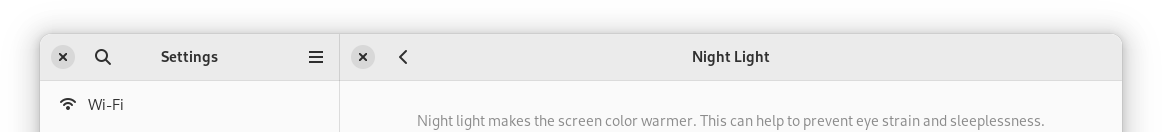

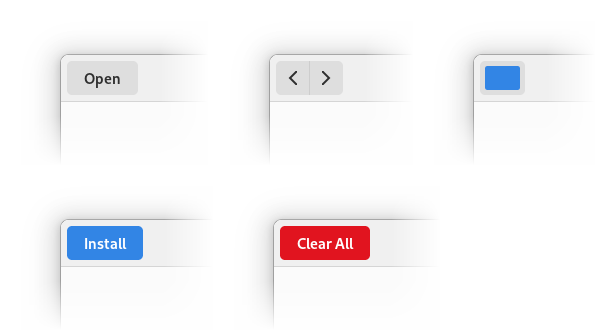

Style changes

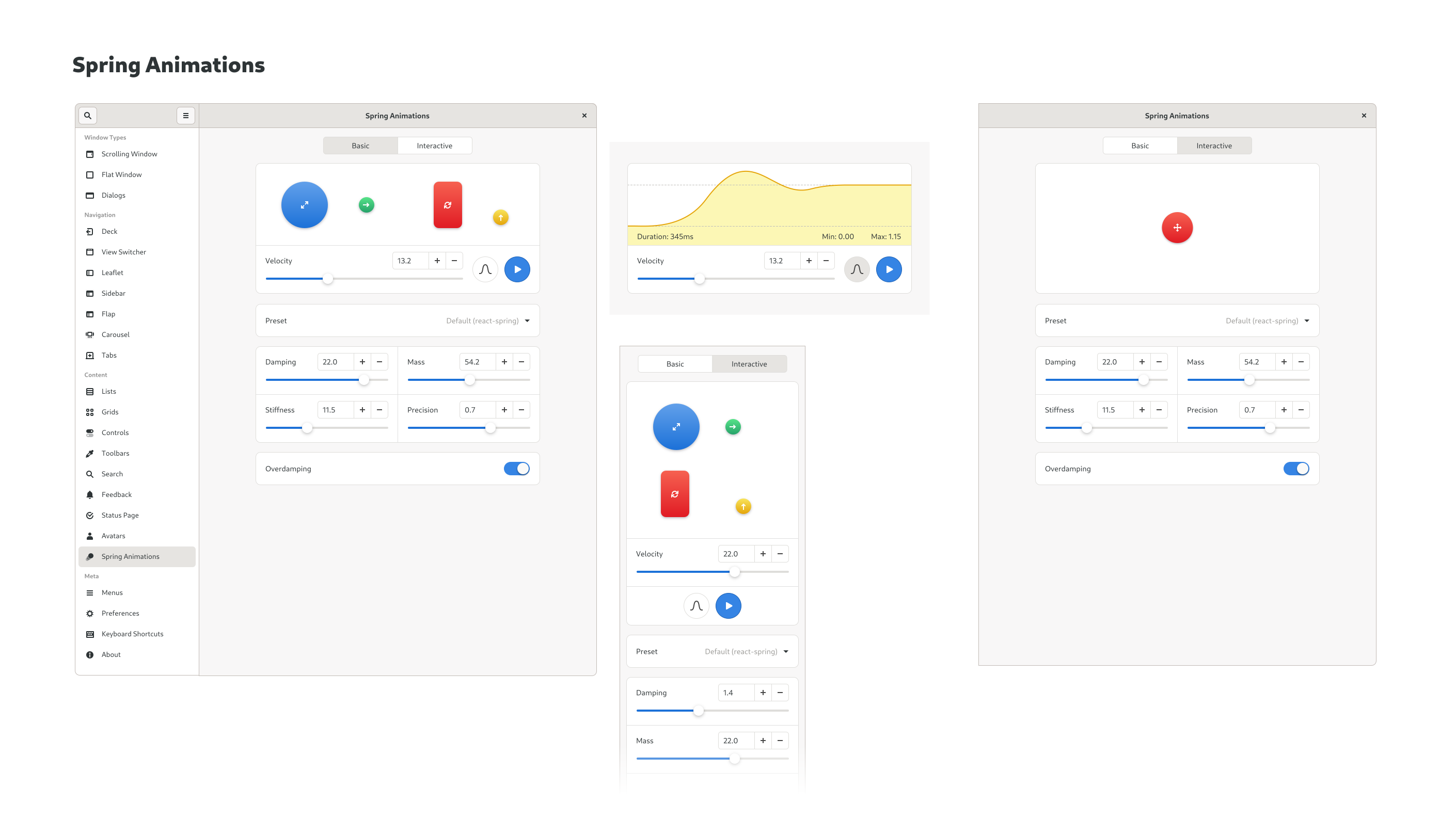

There were a few things that we wanted to do for a while, but that needed variables to be feasible. Now they are feasible, and are implemented.

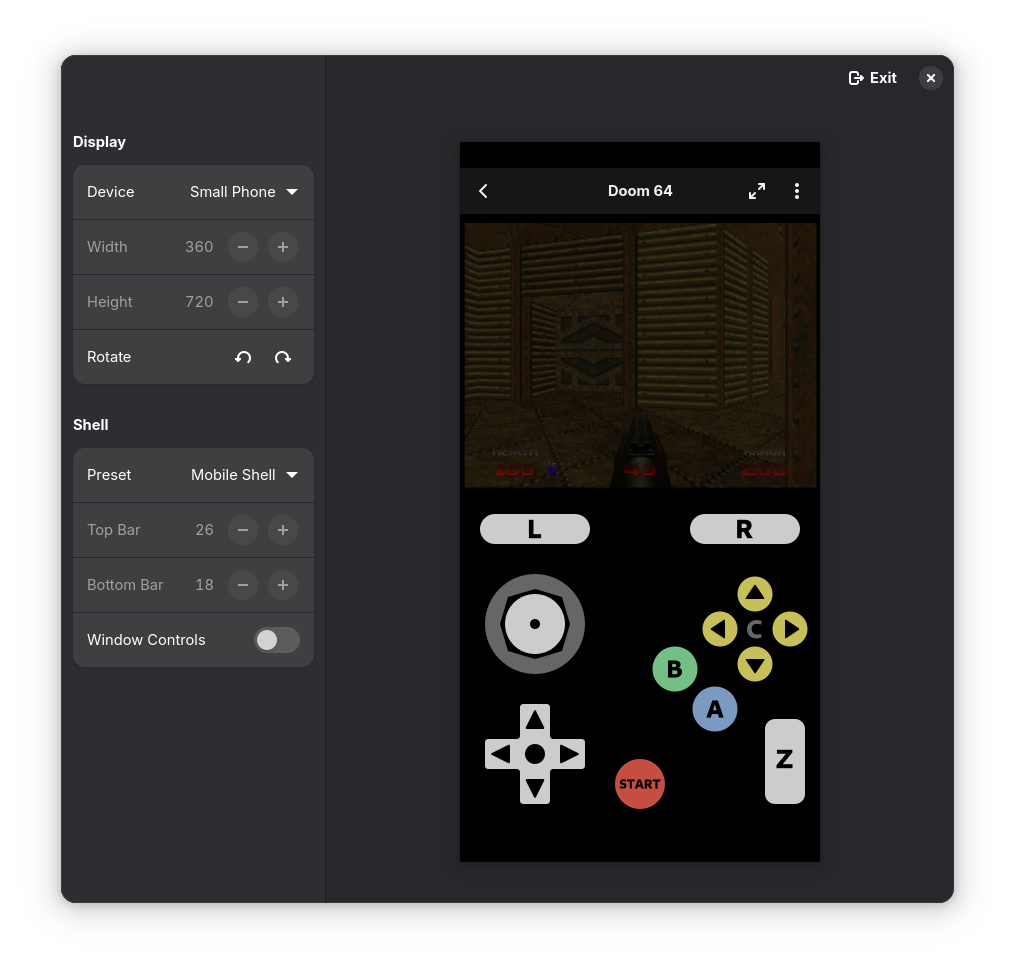

For example, the .osd style overrides accent color to be light grey. Previously this was done with separate overrides for every single widget that uses accent, and in some cases blue accents sneaked through anyway. It also didn’t work with custom widgets defined in apps, unless they special cased it themselves. Now it just overrides the accent color variables and is both much simpler and actually consistent.

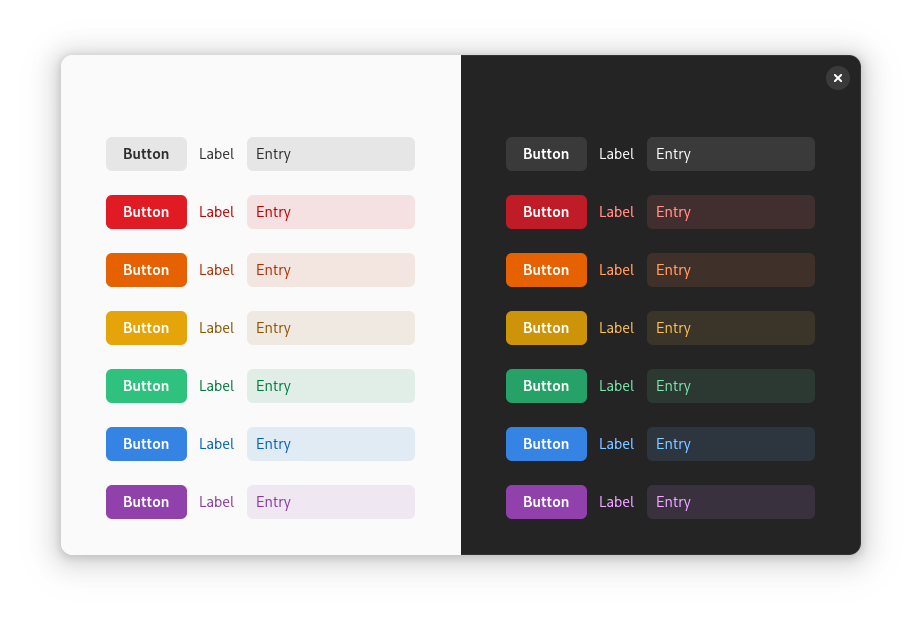

Destructive buttons previously had blue focus rings, and now they are red, matching the buttons themselves. Moreover, apps can easily get custom-colored widgets like this themselves, with matching focus rings.

Since previously we couldn’t override accent color per-widget, the way to recolor buttons (as well as checks, switches etc) was to just set background-color and color properties manually. It worked, but obviously didn’t affect focus rings, and focus rings are complicated, so doing it manually wouldn’t be feasible. They have a very specific color with a specific opacity, a different opacity for the high contrast mode, and the actual selector changes a lot between widgets. In case of buttons it’s button:focus:focus-visible, for entries it’s entry:focus-within and so on. Not very good, so we didn’t encourage apps to change focus rings, and didn’t change them on destructive buttons either.

But now that we have variables, people can just override the accent color, and focus rings will follow the suit. For example, to make a green button, an app can just apply .suggested-action and override accent on it to green:

So, for example, Calculator can now make its big orange result button orange and have matching focus ring on it without changing accent color in the whole app.

Because of that, the .opaque style class has been deprecated. Instead, apps are encouraged to use .suggested-action like above.

Meanwhile, GtkEntry with .error, .warning and .success style classes have had red focus rings, as an exception. Later, AdwEntryRow gained the same styles, but that was messy overall. But now these style classes just set accent color in addition to text color, so these styles aren’t special cases anymore – they will work with any widget.

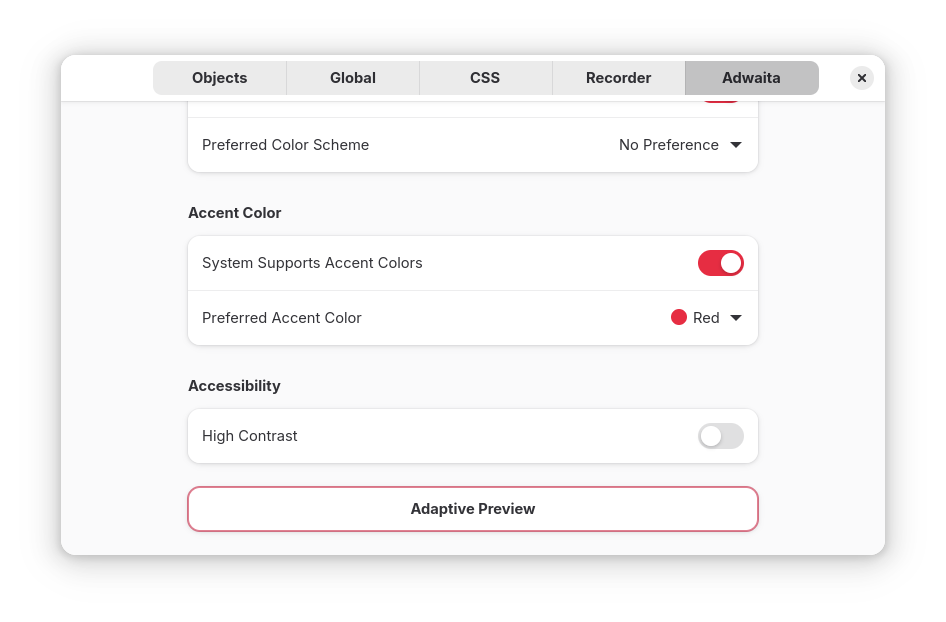

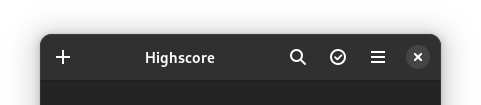

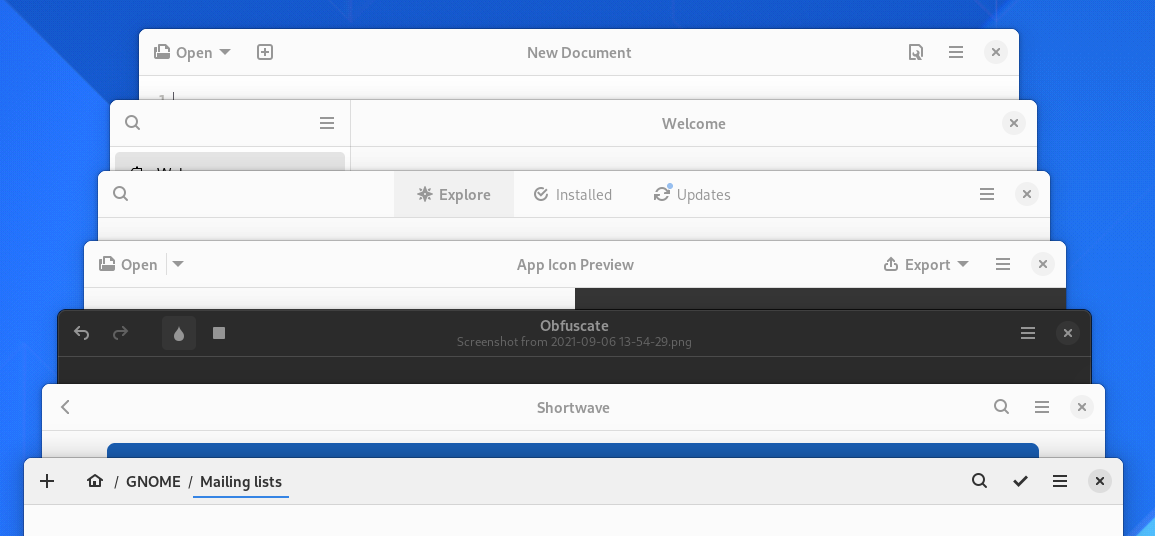

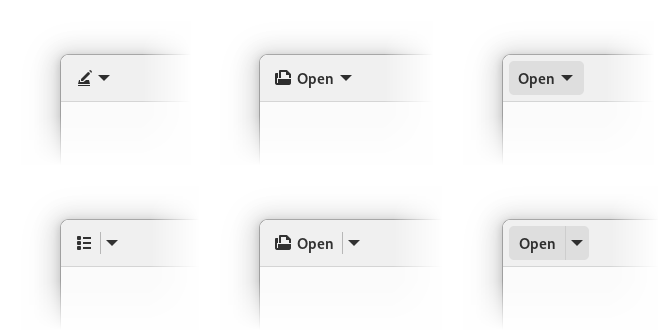

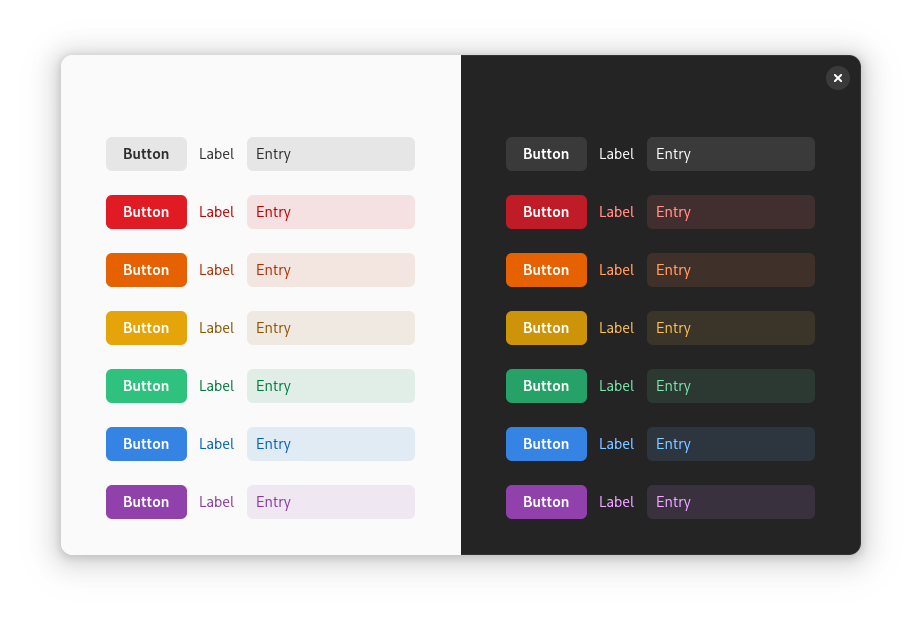

Deriving accent colors

Since 1.0, libadwaita has had two separate accent colors: --accent-bg-color and --accent-color. The former is suitable for use as a background on widgets like buttons, checks and switches, but usually has too low contrast to be used as a text color. The latter has a higher contrast, suitable for use as text, but it doesn’t work well as a background.

That’s a bit confusing, and I’ve seen a lot of apps misusing them. Some apps set a custom accent color and just set them to the same value, so they don’t have enough contrast. Some apps mix up the colors and use the wrong one. And so on.

It would be really nice if we could generate one from the other one. Previously this was firmly in the realm of pipe dreams, but now that we have relative colors, it’s a lot more feasible.

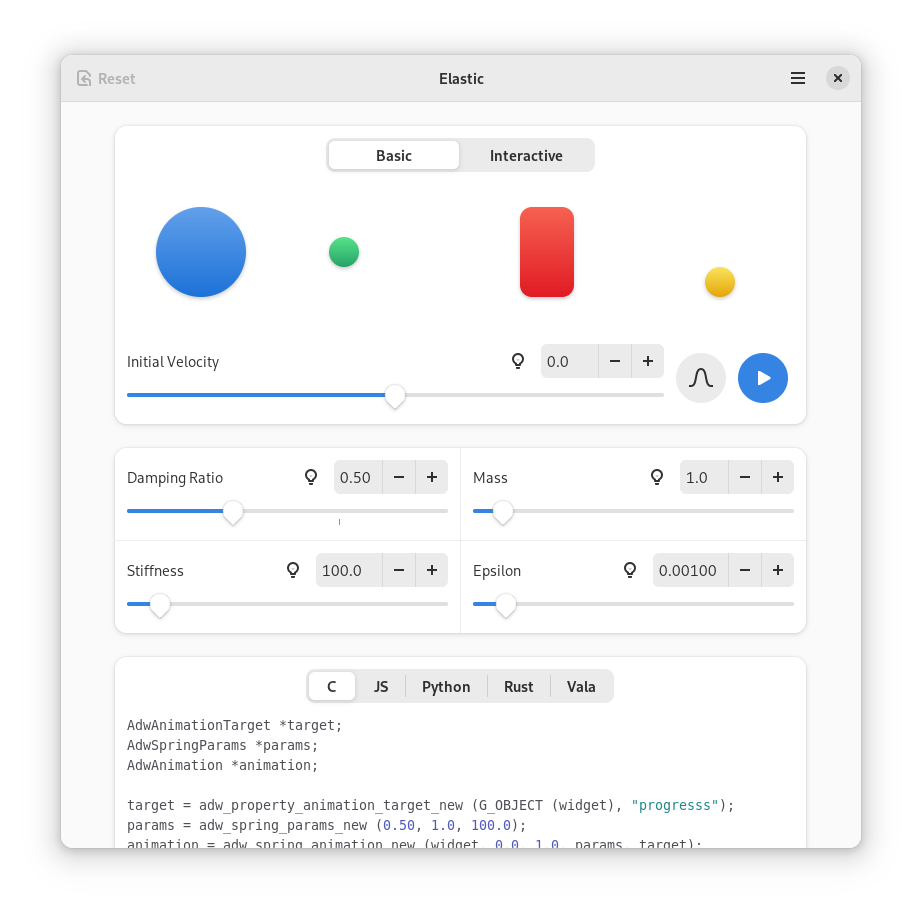

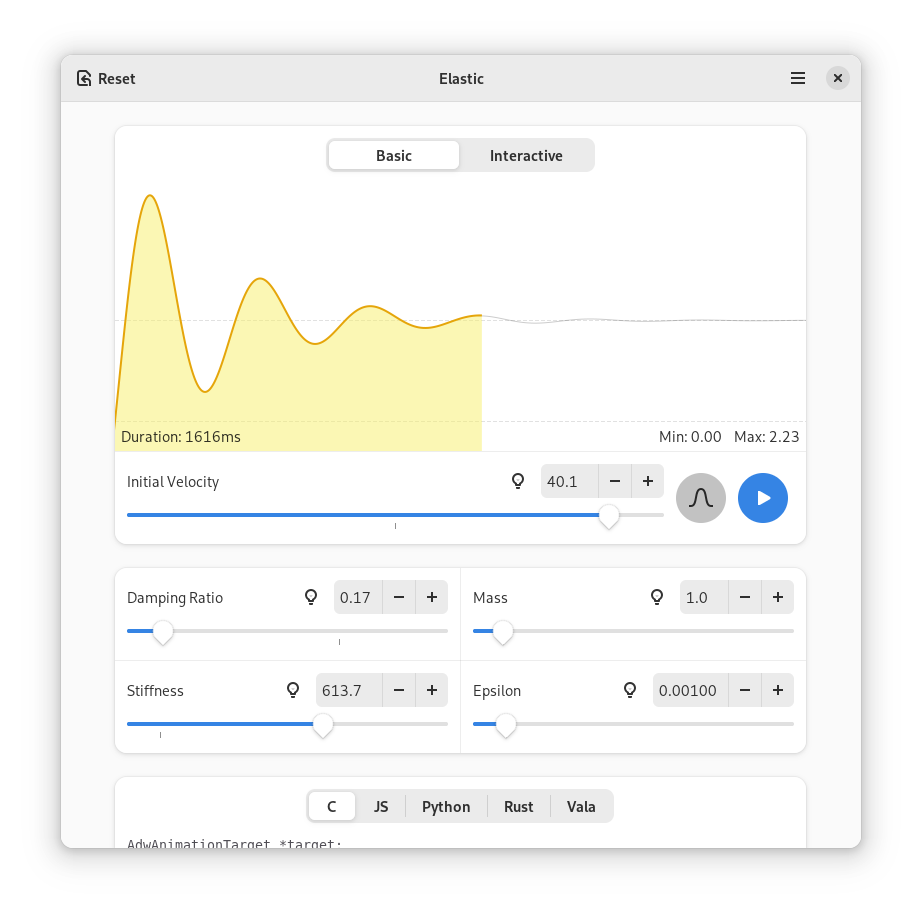

For example, the following functions produce consistently good colors for light and dark styles respectively:

/* light style */

--accent-color: oklab(from var(--accent-bg-color) min(l, 0.5) a b);

/* dark style */

--accent-color: oklab(from var(--accent-bg-color) max(l, 0.85) a b);

Here are some examples, for both light and dark style:

Unlike the HSL color space, Oklab is perceptual and lightness stays uniform regardless of other channels. So, as simple as it sounds, just limiting the lightness does the job. In fact, we could even do this:

/* light style */

--accent-color: oklab(from var(--accent-bg-color) 0.5 a b);

/* dark style */

--accent-color: oklab(from var(--accent-bg-color) 0.85 a b);

The downside is that --accent-bg-color: black; in light style would produce a dark gray --accent-color instead of black, and --accent-bg-color: white; in dark style would produce a light gray accent instead of white. This may be fine, but the goal here is to ensure minimum contrast, not to prevent too much contrast.

These functions are also in the docs, but there’s one problem.

So why not do it automatically?

Say, we define these variables at :root, as follows:

:root {

--accent-bg-color: var(--blue-3);

--accent-color: oklab(from var(--accent-bg-color) min(l, 0.5) a b);

}

Then, we override accent color for a specific widget:

my-green-widget {

--accent-bg-color: var(--green-3);

}

But --accent-color would still be blue, so the we would need to re-declare it – not very good.

There is a way to get around that – use a wildcard:

* {

--accent-color: oklab(from var(--accent-bg-color) min(l, 0.5) a b);

}

But that has its own downsides – it may impact performance and memory use, like wildcards in CSS tend to do. That said, I haven’t profiled it and maybe it’s not that bad.

Either way, for now we’re keeping --accent-color separate, but apps overriding it are welcome to use the above functions themselves, instead of picking the color by hand. Maybe in future we’ll figure something out.

Future

There are a lot more things we could do if we didn’t need to care about backwards compatibility. For example, instead of having colors like --shade-color that are always supposed to be partially-transparent black, we could just provide the opacity as a variable. (or maybe even derive it from background color lightness?) We could specify accent color as a hue and/or chroma in the Oklch color space, while keeping the lightness consistent. And so on.

Can we drop SCSS entirely?

A lot of people asked this or assumed that these additions were the few missing pieces for dropping it.

As much as I’d like to, not yet. While this helps with reducing dependency on it a bit, there are still a lot of things that cannot be replicated, like @mixin and @extend. It also allows us to have private variables and control what gets exposed as API, which is pretty important for a library.

In fact, there are situations where we had to add more SASS-specific things, tho mostly because we’re using the older (and unmaintained) sassc compiler instead of dart-sass. Being old and unmaintained, sassc doesn’t support the modern rgb() syntax, and errors out. There is a way to placate it, by using RGB() instead, but that’s a hack. It also doesn’t like the slash symbol (well, solidus) and thinks it’s division. This can be worked around with string interpolation, but it’s a hack too.

So, instead of this:

rgb(0 0 0 / if($contrast == 'high', 80%, 5%))

we have to do this:

RGB(0 0 0 / #{if($contrast == 'high', 80%, 5%)})

(and then keep in mind that SASS won’t see this as a color, so you can’t use functions like transparentize() on it, not that we really need to)

Finally, the opacity() function (used within the filter property) kept getting replaced with alpha(), but only when it contained a variable instead of a literal:

filter: opacity(55%);

/* SASS output: filter: opacity(55%); */

filter: opacity(var(--disabled-opacity));

/* SASS output: filter: alpha(var(--disabled-opacity)); */

I worked around this by once again manipulating case. opacity() was affected, but Opacity() wasn’t.

All of this could be solved by migrating to dart-sass. This is difficult, however – GNOME SDK doesn’t have any Dart components at the moment, and it would need to build that first. A lot of manifests I’ve seen on Flathub just use pre-built SASS compiler, but I doubt this would be acceptable for the SDK. So, for now we’re stuck with sassc. Help is very much welcome, particularly with the SDK side of things.

Programmatic API?

Another question I see fairly often: is it possible to read variables programmatically?

The short answer is: no.

The longer answer is: variables can be anything. The only way to read them would be as a string. At that point, you’d need to have a CSS parser in your app to actually parse them into a useful value.

For example, let’s say we have a variable declaring a color, like red. One might think: so what, just use gdk_rgba_parse(). Now, what about rgb(0 0 0 / 50%), the modern syntax? gdk_rgba_parse() doesn’t support that, but one might argue it should. Alright, what about this:

color-mix(in oklab, currentColor, var(--something) calc(var(--base-percentage) * 0.5))

This is a potentially valid color, and yet there’s no way gdk_rgba_parse() would be able to parse this – how would it know what currentColor is when you don’t supply it a widget? It would need to resolve other variables somehow. And it would also need a full-blown calc() parser. Yeah, colors get complicated fast. It’s fine when we’re already inside a CSS parser, but gdk_rgba_parse() isn’t one.

Now, could we have a function to get a variable value specifically as a color? Sure, except variables don’t have to be colors. You might also get 3px, 0 or asjdflaskjd. They don’t even have to be valid values, they can also be parts of the values, or even random gibberish. CSS doesn’t even try to compute variables on their own, only insert them into other values when you reference them with var() and then parse and compute that once every reference is resolved. The following is perfectly valid:

my-widget {

--space: srgb-linear;

--r: 100%;

--gb: 0 0;

color: color(var(--space) var(--r) var(--gb) / 50%);

}

So, with that in mind, would API for fetching them be useful? IMO not really. There are very specific cases where it may work (e.g. if you define a variable containing an integer and then treat it as pixels in your code), but they are far too limited, break easily, and arguably are a misuse of CSS anyway.

It would be a bit more feasible if we had @property, as then you can at least guarantee the variable type. Even then the type system is very flexible and one can define things like <color># | <integer>#. The valid variables with this type would be comma-separated lists of colors, and comma-separated lists of integers, so good luck with that. And we don’t even need to go that far: take a look at <image>. It can be a gradient (linear (possibly repeating), radial or conic), a URL, image() which produces a solid color image from a given color, or many other things. At best I can see getters being limited to, say, colors, numbers and dimensions.

Many thanks to:

- Matthias Clasen for reviews and implementing HWB, Oklch and Oklab color spaces, relative colors, color interpolation and math functions.

- STF for funding this work.

- Sonny Piers and Tobias Bernard for organizing everything.