If you are interested in coding for GNOME, but haven’t figured out what to work on, this post is for you.

In my last post, I described an experiment that I’m running for the GNOME 3.14 development cycle. The goal is to make it easier of people to contribute to GNOME, by making it easy to find tasks to work on and getting rapid and effective feedback.

Since I wrote that post, I’ve been working with a number of GNOME application maintainers to get their bugs in a state where it is easy for people to contribute. The result is three apps that have a clear set of bugs that contributors can get to work on today.

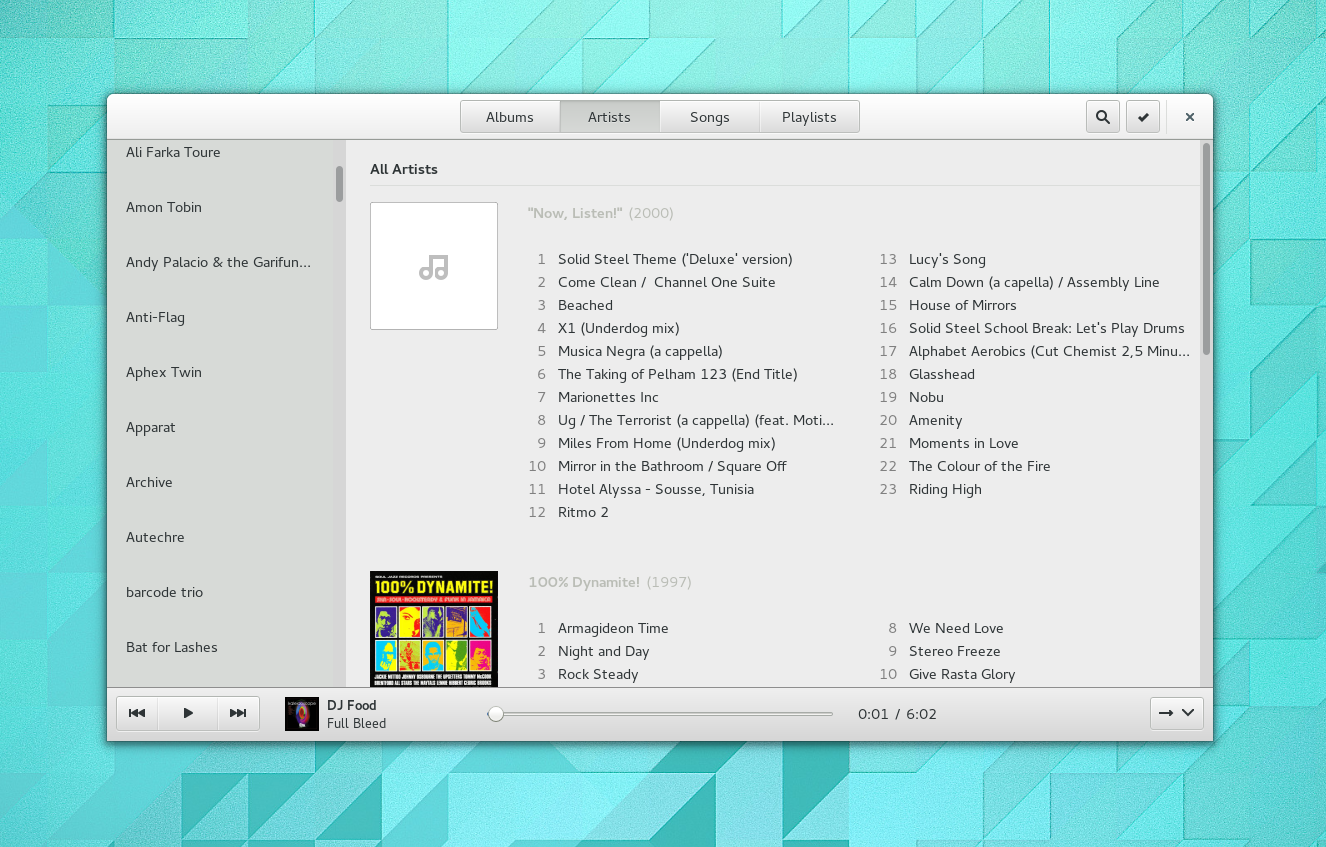

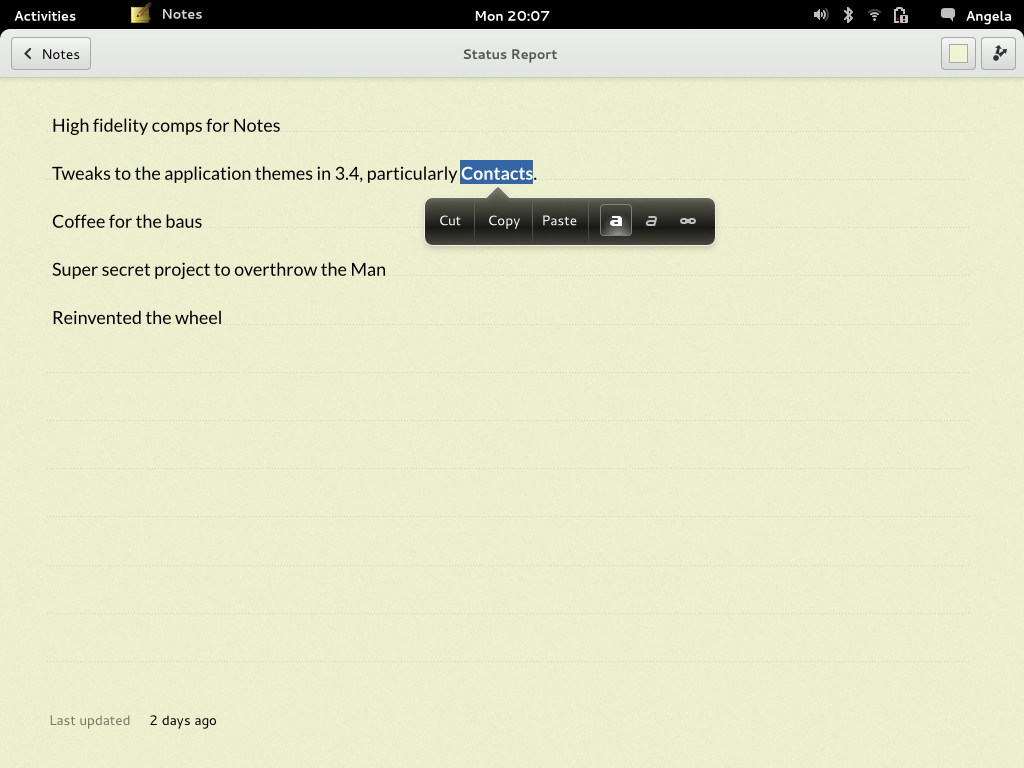

Music

The Music app has been around for a couple of cycles now. It is currently fairly basic, but manages playback fairly well and gives a really nice view of your music collection. This cycle some big new features are planned, like new and improved search and Last.fm integration.

Music has a great development team around it, and is written in Python.

As of today, there are 32 bugs that are available for contributors. Every one of these is in a state where you can get to work on them, and they have all been reviewed by Vadim (the Music maintainer) and myself – so you can be sure that they are things we want.

Some of the bugs are small and address UI niggles, like bug 723144: which aims to give the Artists view a consistent visual style to other sidebars in GNOME. Other bugs are for bigger features, like allowing you to view and play music stored in ownCloud instances. There’s plenty to choose from, and there should be a bug to suit your tastes.

Music is a really promising app, and there are opportunities to play a serious role as it matures.

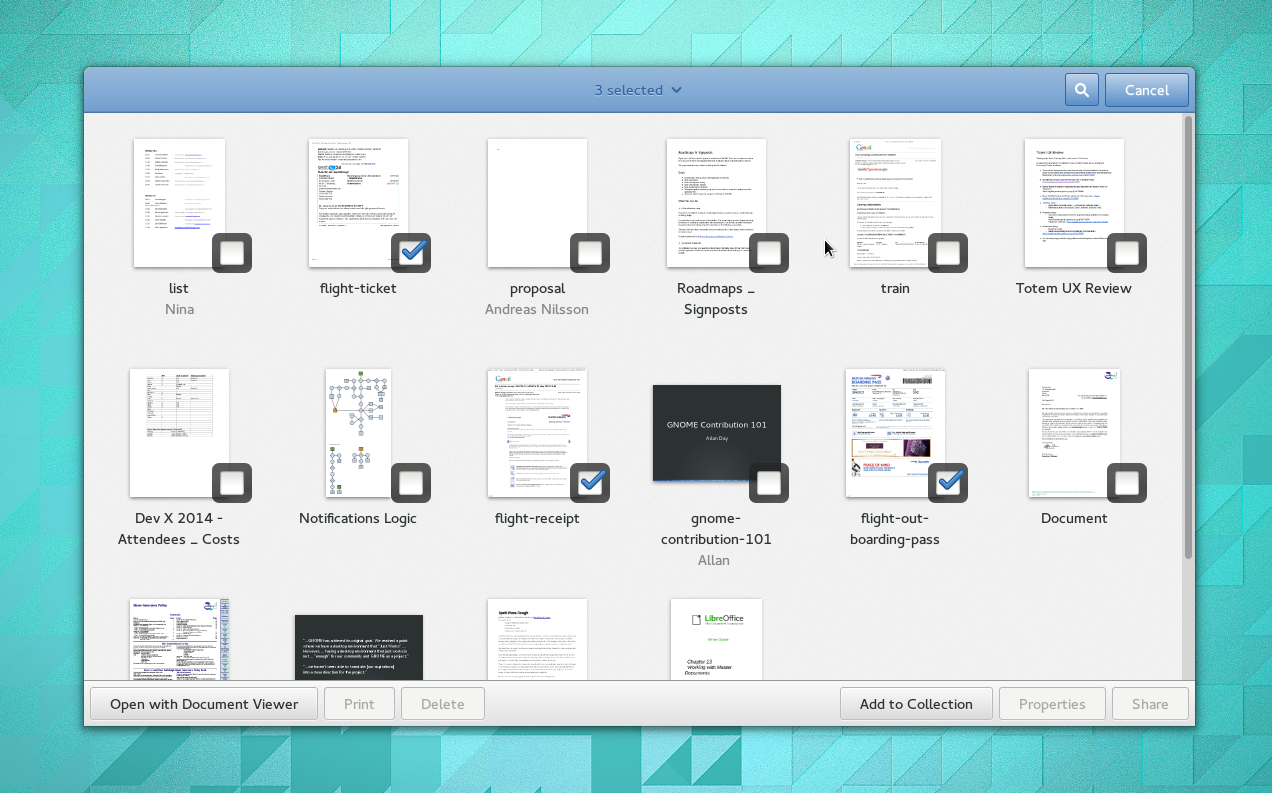

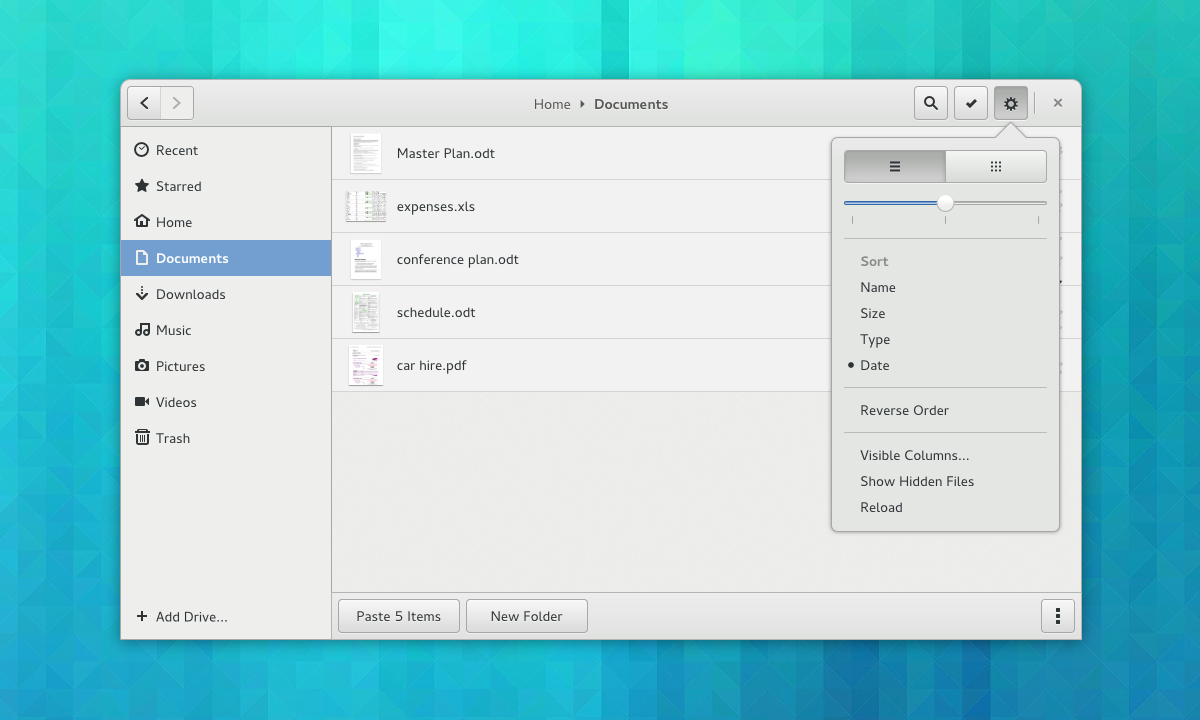

Documents

Documents is one of the original GNOME 3 applications. It has come a long way, and has a lot of cool functionality. I’m not sure that people have made the most of this app in the past, but I think that its utility will become much more obvious with a few changes we have planned, particularly when managing document collections.

Debarshi Ray is currently leading the Documents effort. He’s a great guy and an active maintainer. The application is written in JavaScript.

There are 43 available bugs for Documents. They include functional enhancements that will make the application much more useful. Adding the ability to sort documents in different ways is one of these. Another is making the list view more usable.

We also have some nice UI polish planned, such as using a popover for search options and having a smoother full screen mode.

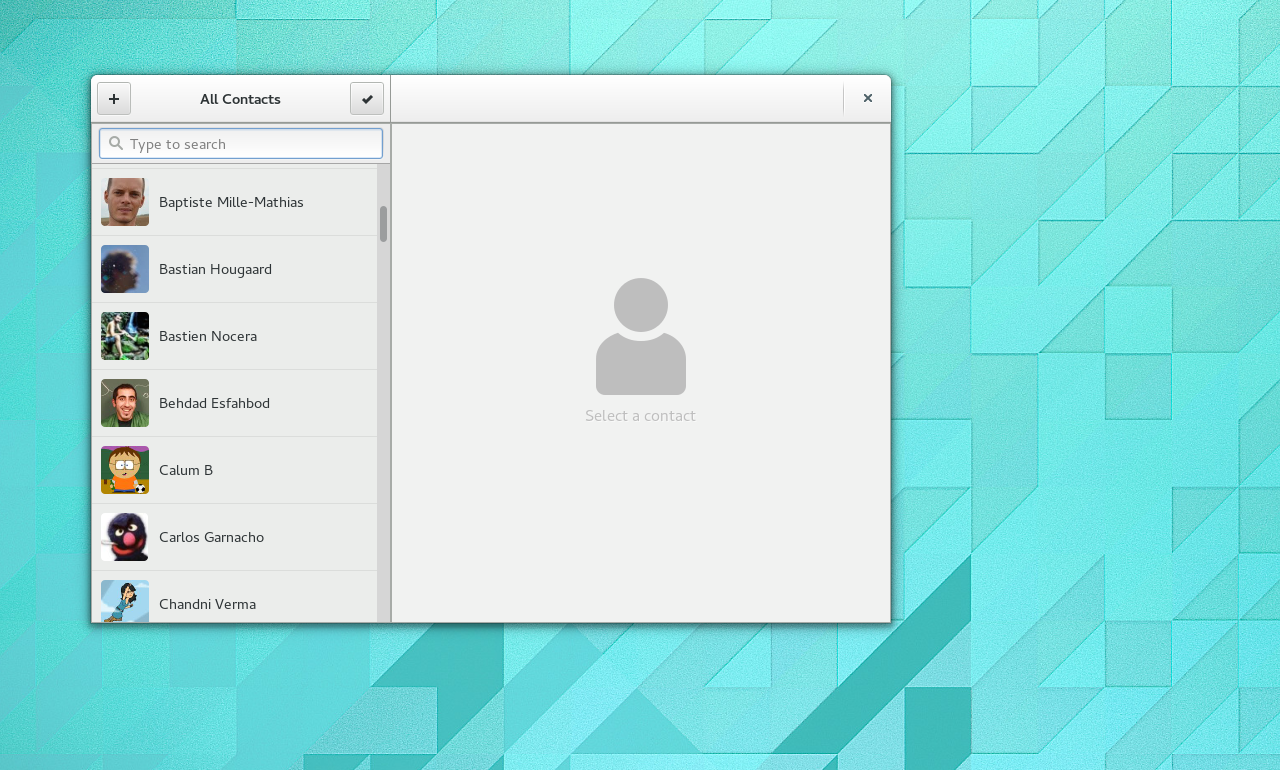

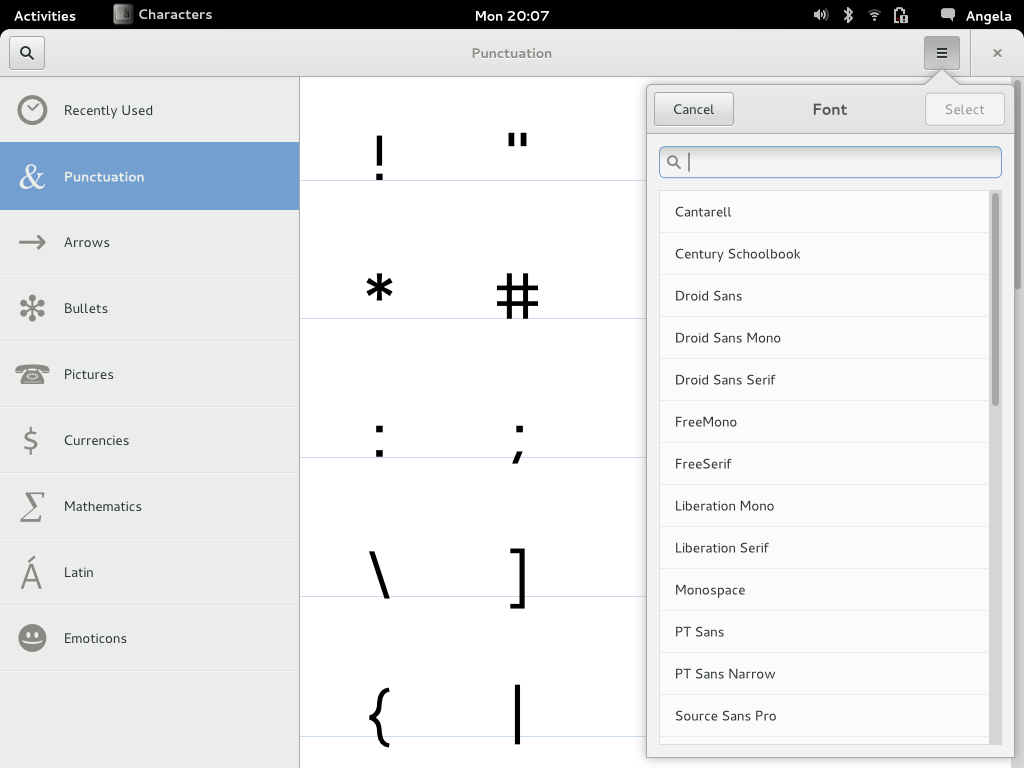

Contacts

Contacts is one of the older GNOME 3 apps. It is written in Vala, and is maintained by Erick Pérez Castellanos, who is awesome.

This is a nice app that can really shine with a bit of work. Right now there are 60 bugs that are available for contributors. Again, there’s lots of small UI issues: in the spirit of Every Detail Matters, these fixes would make a big difference to the overall user experience. For example:

- Bug 696384 – porting the contact linking suggestion box to GtkActionBar.

- Bug 699319 – making the app look better when you don’t have any contacts.

- Bug 703201 – allowing users to select contacts using the right mouse button.

There are also some fun bugs that will hopefully make Contacts a bit more engaging, such as showing maps and status messages from contacts.

What Next

If you want to get involved in GNOME, these applications, and the lists of bugs I’ve pointed to, are the best place to start. The nice thing about these apps is that small fixes will go a really long way, and they all have active maintainers. It would be fantastic if people could help us to make them shine for 3.14.

If other application maintainers want to get involved in this initiative, just get in touch or follow the procedure I described in my last post.