The week of 8th–12th November was Endless Orange Week, a program where the entire Endless OS Foundation team engaged in projects designed to grow our collective learning related to our skills, work and mission. My project was to explore running a complete GNOME desktop in a window on Windows, via Windows Subsystem for Linux.

Why?!

We’ve long faced the challenge of getting Endless OS into the hands of existing PC users, whether to use it themselves or to try it out with a view to a larger deployment. Most people don’t know what an OS is, and even if they have a spare PC find the process of replacing the OS technically challenging. Over the years, we’ve tried various approaches: live USBs, an ultra-simple standalone installer (as seen in GNOME OS), dual-booting with Windows (with a 3-click installer app), virtual machine images, and so on. These have been modestly successful – 5% of our download users are using a dual-boot system, for example – but there’s still room for improvement. (I have a personal interest in this problem space because it’s what I joined Endless to work on in 2016!)

In the last few years, it’s become possible to run Linux executables on Windows, using Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL). Installing the Debian app from the Windows Store gives you a command-line environment which works pretty much like a normal Debian system, running atop a Microsoft-supplied Linux kernel. Most recently, unmodified applications can present X11 or Wayland windows and play audio through PulseAudio; behind the scenes, a Microsoft-supplied distribution with their branches of Weston and PulseAudio exports each Wayland or X11 window & its audio over RDP to the host system, where it appears as a free-standing window like any other. There is also support upstream in Mesa for using the host system’s GPU, with DirectX commands forwarded to the host via a miraculous kernel interface.

This raises an interesting question: rather than individual apps installed and launched from a command line, could the whole desktop be run as a window, packaged up into an easy-to-use launcher, and published in the Windows Store? If so, this would be a nice improvement on the other installation methods we’ve tried to date!

Proofs of concept

I spent last week researching this. Yes, you can indeed run a complete GNOME desktop under WSL. I tried two approaches, which each have strengths and weaknesses. I worked with Debian Bookworm, which has GNOME 41 and an up-to-date Mesa with the Direct3D backend. Imagine telling someone 20 years ago that Debian would one day include development headers for DirectX in the main repository!

I packaged up my collection of scripts and hacks into something which can build a suitable rootfs to import into WSL and launch either demo with a single command. There may be things that I got working in my “pet” container that don’t quite work in this replicable “cattle” container, but I did my best.

GNOME desktop as X11 app

GNOME Shell can be run as a so-called “nested session”, with the entire desktop appearing as a window inside your existing session. Thanks to my team-mate Georges Stavracas for his help understanding this mode, and particularly the surprising (to me) detail that the nested session can only be run as an X11 window, not a Wayland window, which explained some baffling errors I saw when I first tried to get this going.

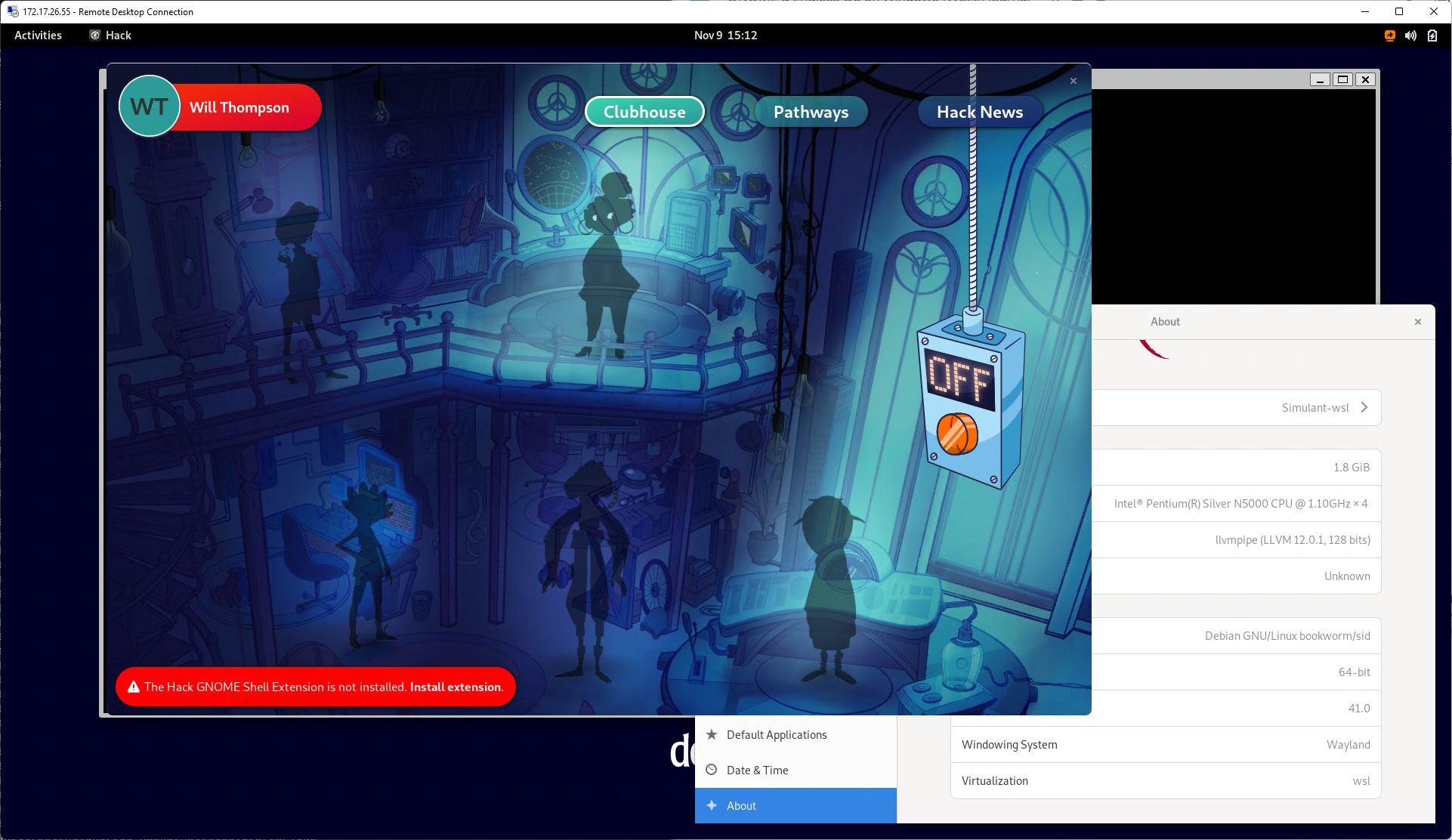

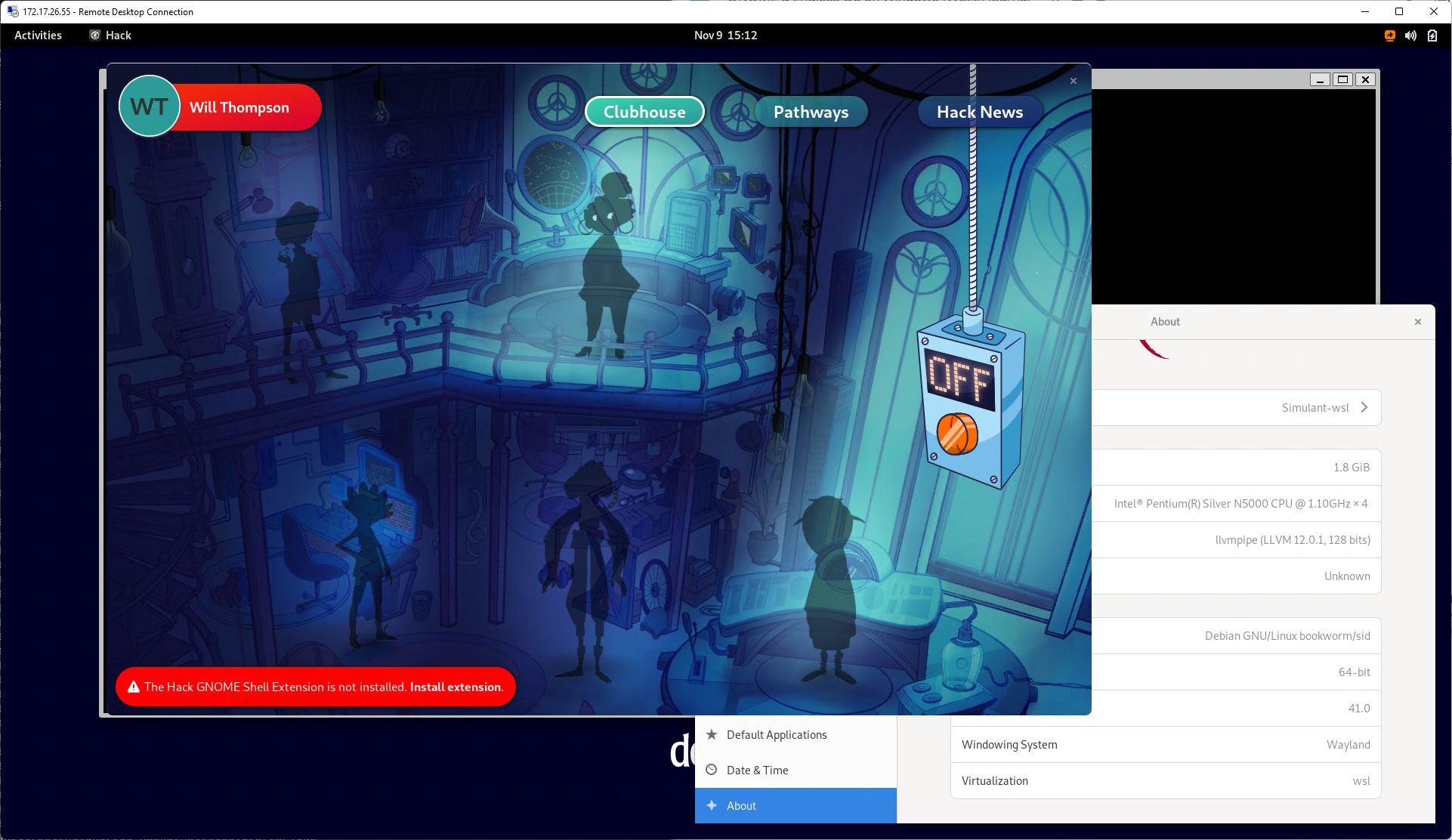

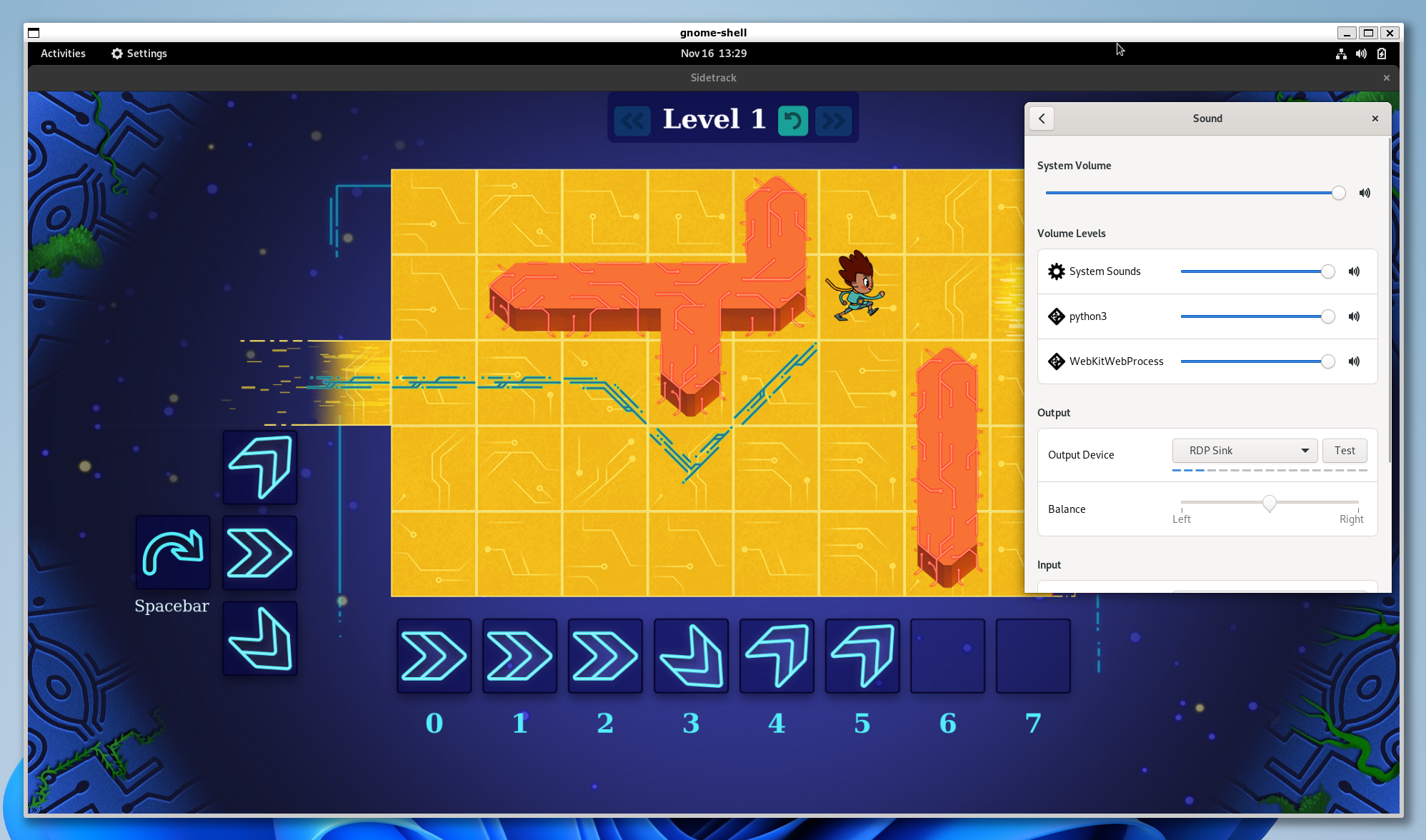

Once you’ve got enough of the environment GNOME expects running (more on this below), you can indeed just run it with a carefully-crafted set of environment variables and command-line arguments, and it appears on your Windows system, resplendent with Weston’s window decorations:

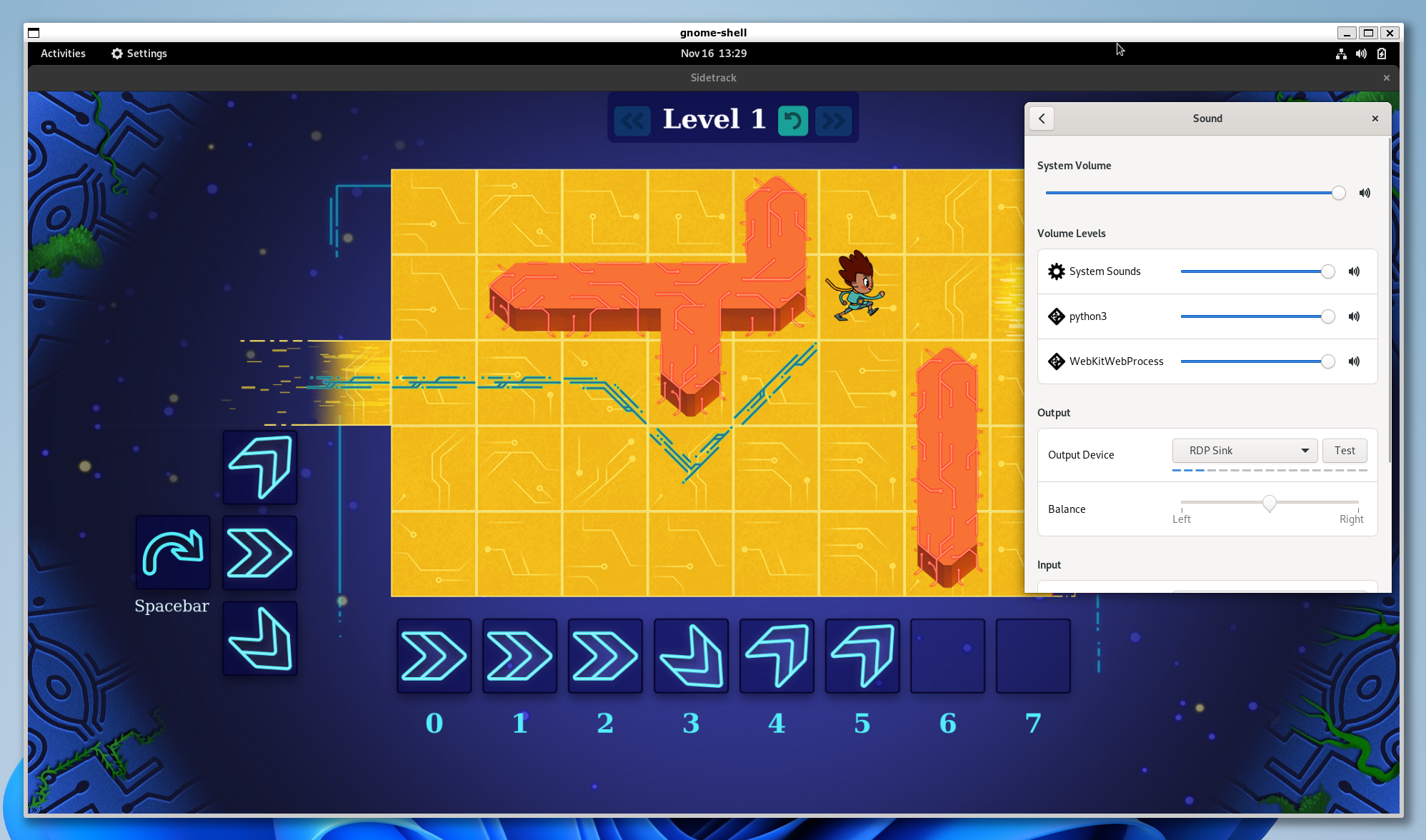

Apps can even emit sound over PulseAudio as normal, or at least they could once I fixed an edge case in Flatpak’s handling of the PulseAudio socket. It’s hard to show audio in a screenshot, but you can see the sounds being emitted by Sidetrack (the WebKitWebViewProcess) as well as Hack somewhere in the background (the python3 process), both of which are Flatpak apps, and the RDP sink as output.

So on the face of it this seems quite promising! But Shell’s nested mode is primarily intended for development, with the window size fixed at launch by an environment variable with DEBUG in its name.

I found WSLg to be quite fragile. WSLg’s Xwayland often fell over for unknown reasons. I had to go out of my way to install a newer Intel graphics driver than would automatically be used, to get the vGPU support needed for Mesa’s Direct3D backend to work. But having done this, on one of my machines, the driver would just crash with SIGILL – apparently the driver unconditionally uses AVX instructions even if the CPU doesn’t support them. On my higher-end machine, most apps worked fine, but Shell on this stack would display just a few frames and then hang. In both cases, I could work around the problem by forcing Mesa to use software rendering, but this means losing one of the key advantages of WSLg!

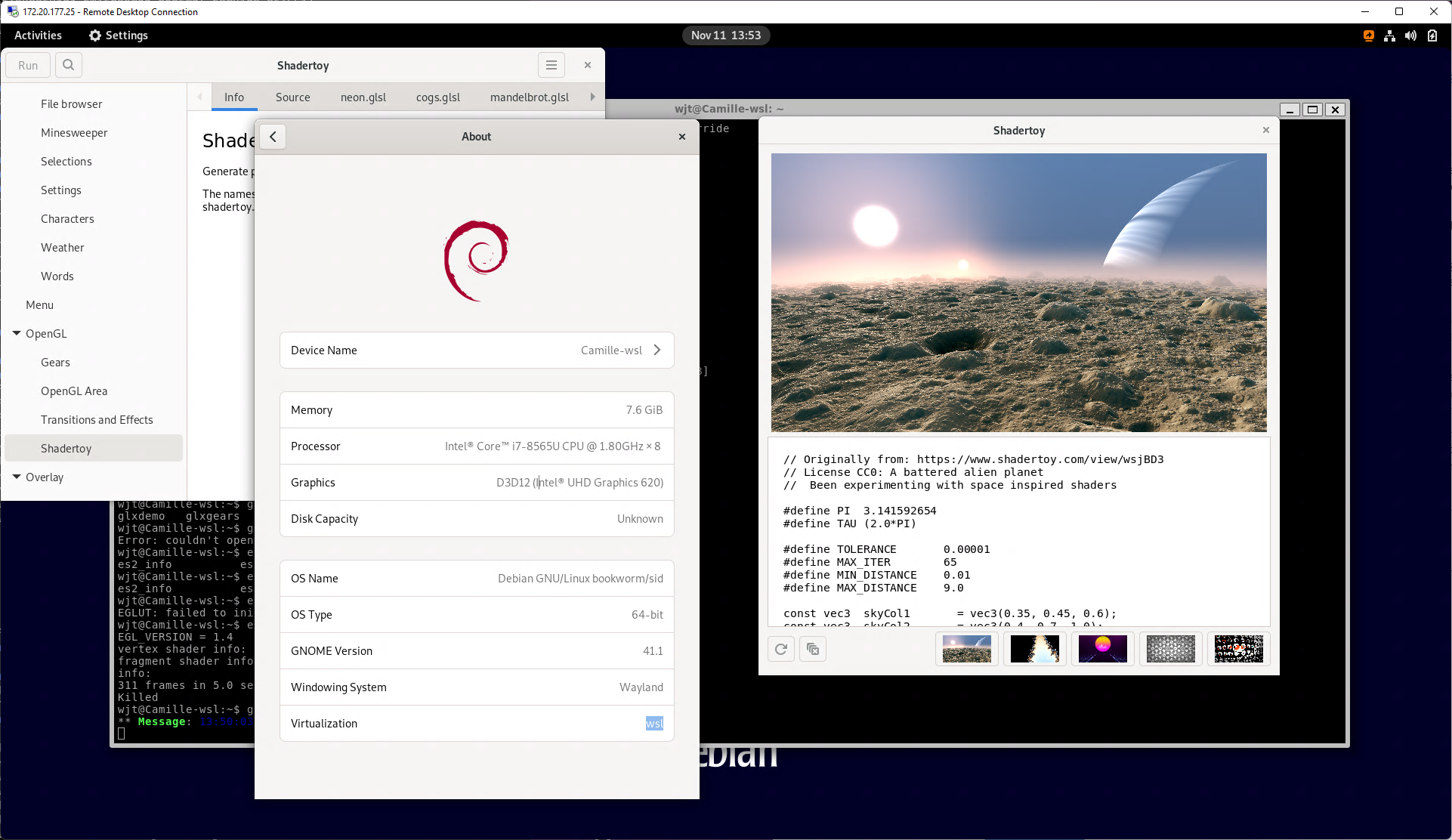

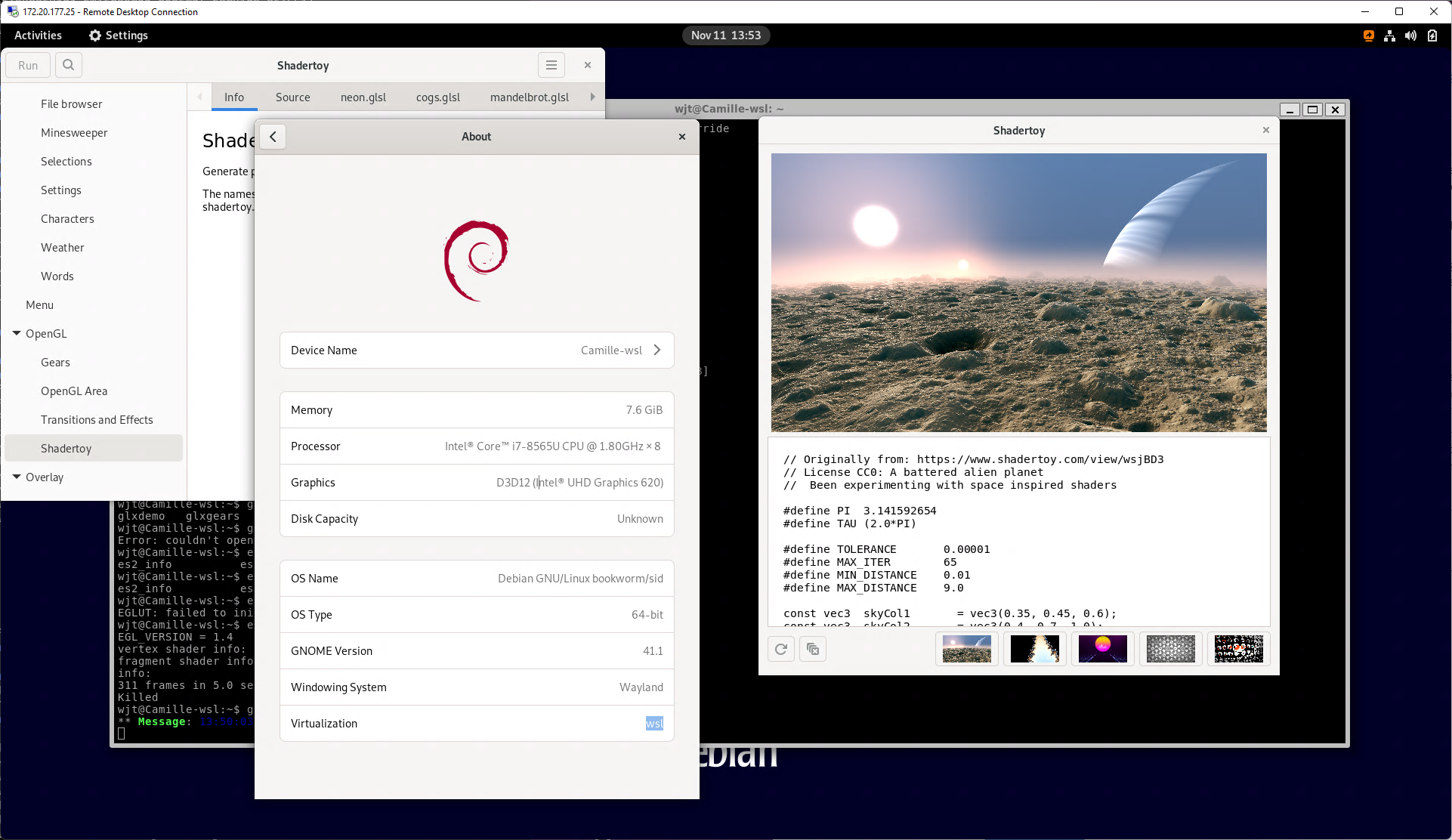

Another weird anecdote: using the D3D12 backend, the GTK demo app’s shadertoy demo works fine, but its gears demo doesn’t render anything – and nor does glxgears! Apparently D3D12 just doesn’t like gears⁈

Thanks to Daniel Stone at Collabora for his patient help navigating Mesa and D3D12 passthrough.

GNOME desktop exported over RDP

In the past few GNOME releases, it’s become possible to access the desktop remotely using RDP. This is Windows’ native remote-access protocol, and is also the mechanism used by WSLg to export windows and audio to the host.

So another approach is to launch GNOME Shell in its headless mode, and then explicitly connect to it with Windows’ RDP client. A nice touch in WSL is that, by the magic of binfmt_misc and an automatic mount of the host system’s drive, you can invoke Windows executables on the host from within the WSL environment, so a single launch script can bring up GNOME, then spawn the Windows RDP client on the host with the correct parameters. (This is how WSLg works too.)

Not pictured below are the ugly authentication and certificate warning dialogs during the connection flow:

Here, GNOME Shell is (AFAICT) rendering using Mesa’s accelerated D3D12 backend, as are GL applications running on it (the GTK 4 Shadertoy demo). But in this model we lose WSLg’s PulseAudio forwarding, and its use of shared memory to send the pixel contents of the desktop to the client. Both of these are solvable problems, though. GNOME Remote Desktop uses the same RDP library, FreeRDP, as WSLg, and all the other supporting code on the Linux side is open-source. GNOME Remote Desktop uses Pipewire rather than PulseAudio, and Mutter rather than Weston, so WSLg’s RDP plugins for PulseAudio and Weston could not be used directly, but audio forwarding over RDP seems a desirable feature to support for normal remoting use-cases. Supporting the shared-memory transport for RDP in GNOME Remote Desktop is perhaps a harder sell, but in principle it could be done.

Just like the nested session, the dimensions of a headless GNOME Shell session are currently fixed on startup. But again I think this would be desirable to solve anyway: this already works well for regular virtual machines, and when connecting to Windows RDP servers.

Rough edges

When you start a WSL shell, PID 1 is an init process provided by WSL, and that’s pretty much all you have: no systemd, no D-Bus system or session bus, nothing. GNOME requires, at least, a functioning system and session bus with various services on them. So for this prototype I used genie, which launches systemd in its own PID namespace and gives you shells within. This works OK, once you change the default target to not try to bring up a full graphical session, disable features not supported by the WSL kernel, and deal with something trampling on WSLg’s X11 sockets. (I thought it is systemd-tmpfiles, but I tried masking the x11.conf file with no success, so I hacked around it for now.) It may be easier to manually launch the D-Bus system bus and session bus without systemd, and run gnome-session in its non-systemd mode, but I expect over time that running GNOME without a systemd user instance will be an increasingly obscure configuration.

Speaking of X11 sockets: both my demos launch GNOME Shell as a pure Wayland compositor, without X11 support. This is because Mutter requires the X11 socket directory to have the sticky bit set, for security reasons, and refuses to start Xwayland if this is not true. But on WSLg /tmp/.X11-unix is a symlink; it is not possible to set the sticky bits on symlinks, and Mutter uses lstat() to explicitly check the symlink’s permissions rather than its target. I think it would be safe to check the symlink’s target instead, provided that Mutter also checked that /tmp had the sticky bit (preventing the symlink from being replaced), but I haven’t fully thought this through.

WSL is non-trivial to set up. The first time you try to run a WSL distro installed from the Windows Store, you have to follow a link to a support article which tells you how to install WSL, which involves a trip deep into the Settings app followed by a download and reboot. As mentioned above, I also had issues with the vGPU support in Intel’s driver on both my systems, which I had to go out of my way to install in the first place, and WSLg’s Xwayland session was somewhat unstable. So I fear it may not be much easier for a non-technical user than our existing installation methods. Perhaps this will change over time.

GNOME Remote Desktop’s RDP backend needs some manual set-up at present. You have to manually generate a TLS key and certificate, set up a new username & password combo, and set the session to be read-write. You also have to arrange for the GNOME Keyring to be unlocked in your headless session, which is a nice chicken-and-egg problem. Once you’ve done all this (and remembered to install a PipeWire session manager in your minimal container) it works rather nicely, and I know that design and engineering work is ongoing to make the set-up easier.

Conclusions

Although I got the desktop running, and there are some obvious bits of follow-up work that could be done to make the experience better, I don’t think this is currently a viable approach for making it easier to try GNOME or Endless OS. There is too much manual set-up required; while it might be possible to bundle some of the Linux side of this into the WSL wrapper app, installing WSL itself is still quite cumbersome, if not exactly rocket science. The many moving parts are still rather new, and I hit various crashes and strange behaviour. Even with software rendering, the performance was fine on my relatively high-end developer laptop, but performance was pretty bad on my normal Windows machine, a lower-spec device that might be more representative of computers in general.

I do still think this general approach of running the desktop windowed in a container on a foreign OS is an interesting one to keep an eye on and re-evaluate periodically. Chrome OS is another potential target, since it also supports running arbitrary Linux containers with Wayland forwarding, though my understanding is that it also involves rather a lot of manual set-up and is not supported on managed devices or when parental controls are in use…

I was happy to experience first-hand the progress GNOME has made in supporting RDP. This kind of functionality may not be important to most GNOME developers and enthusiasts but it’s really important in some contexts. I used to work in an environment where I needed remote access to my desktop, and RDP was the only permitted protocol. Back in 2014, the tools to do this on my Linux system were truly dire, particularly if you want to access a normal desktop remotely rather than a virtualised desktop; by contrast, accessing my Windows system from a Windows, Linux or macOS client worked really well. GNOME Remote Desktop has made some big strides in the right direction, with better integration with the desktop and fewer fragile hacks. I’ll keep watching this space with interest.

WSL itself is also an impressive technical achievement, and the entire Linux side of it is free software. There is nice integration with the host system – for example, you can run Visual Studio Code on the host by running code in WSL, and everything works transparently.

On a personal level, I learnt many new things during the course of Endless Orange Week. Besides learning about WSL, I also learnt how to break on a syscall in gdb (catch syscall 16 for ioctl() on x86_64) and inspect the parameter registers; how Mesa chooses its backend (fun fact: most of the modules in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/dri/ are hardlinks of one another); the importance of a PipeWire session manager; more about how PID and mount namespaces work; and so on. It was a nice change from my usual day-to-day work, and I think the research is valuable, even if it doesn’t immediately translate into a production project.