Nowadays, digital content is all about the cloud. Indeed, in GNOME we’ve been pushing to integrate with cloud-based content through our new content apps, like Documents, Photos, Music and Videos. This is important work and needs to continue.

However, local files are still central to the way that many people work, and are an essential part of lots of workflows. This means that, while cloudy things are important, it is also important that we pay attention to the experience of working with local files in GNOME. It is for this reason that a group of us has been working on a plan to improve the state of Nautilus, our venerable file browser.

The new designs are fairly extensive and cover a lot of ground. In the rest of this post I’ll try to describe as much as I can. As always, they are not set in stone and will evolve. Questions, comments and feedback are most welcome, and will help us to develop them further.

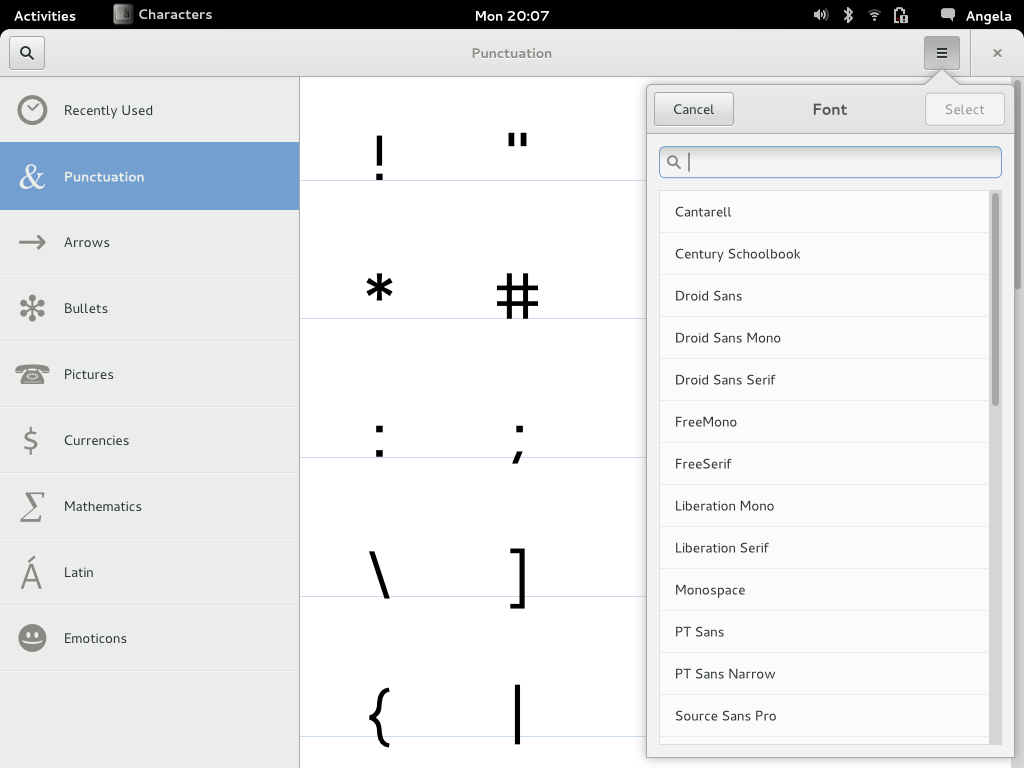

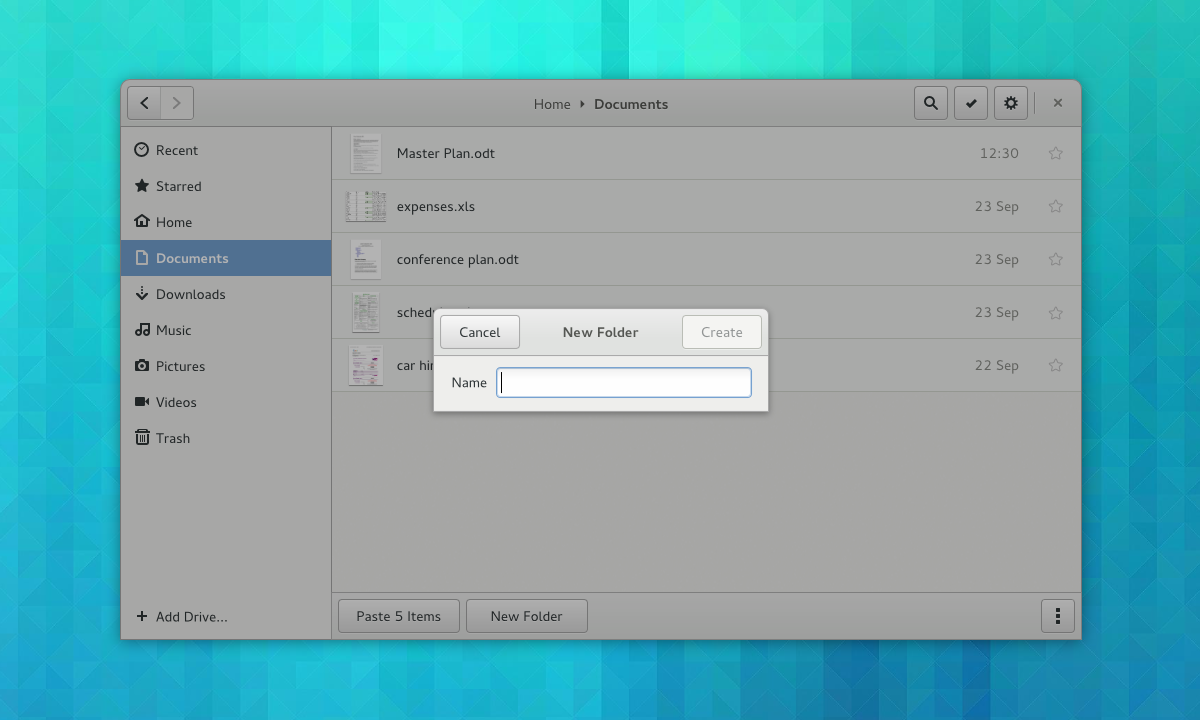

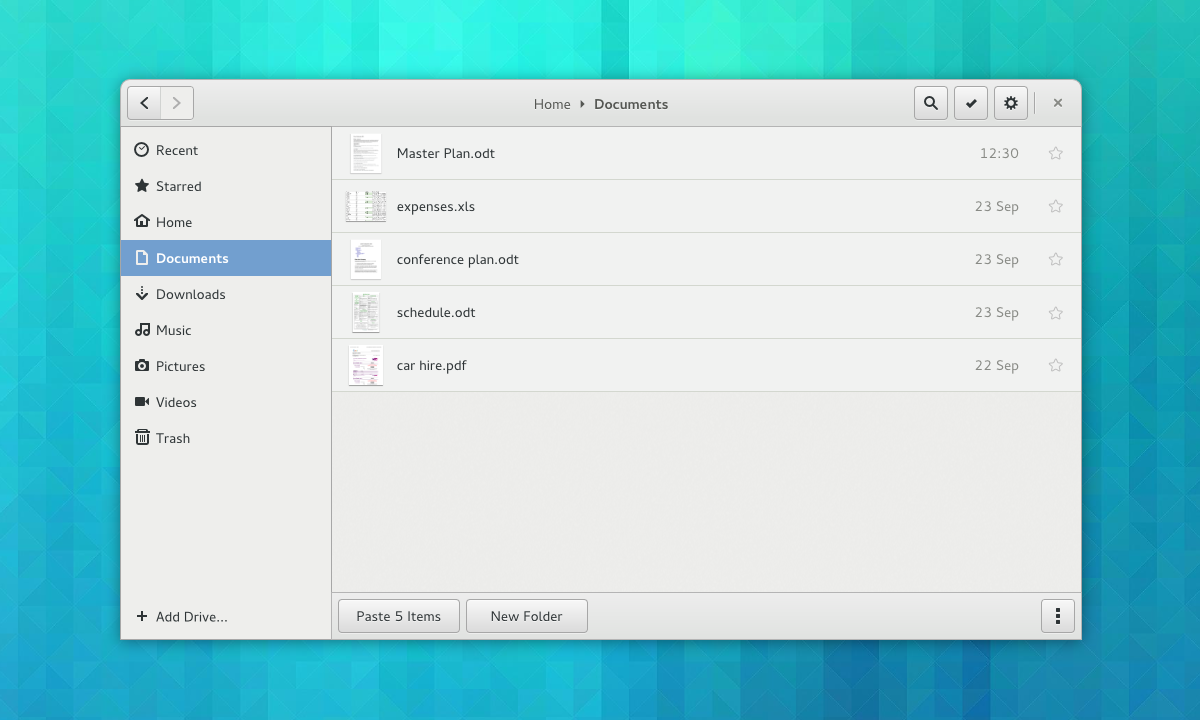

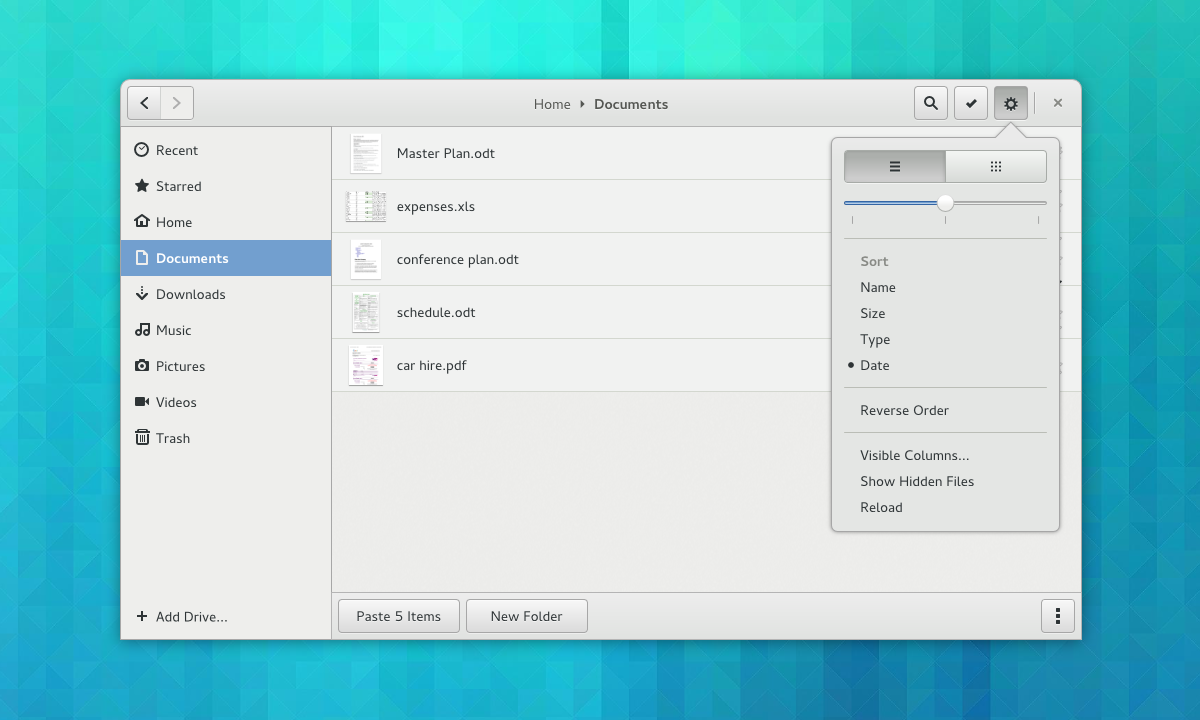

Lists & Grids

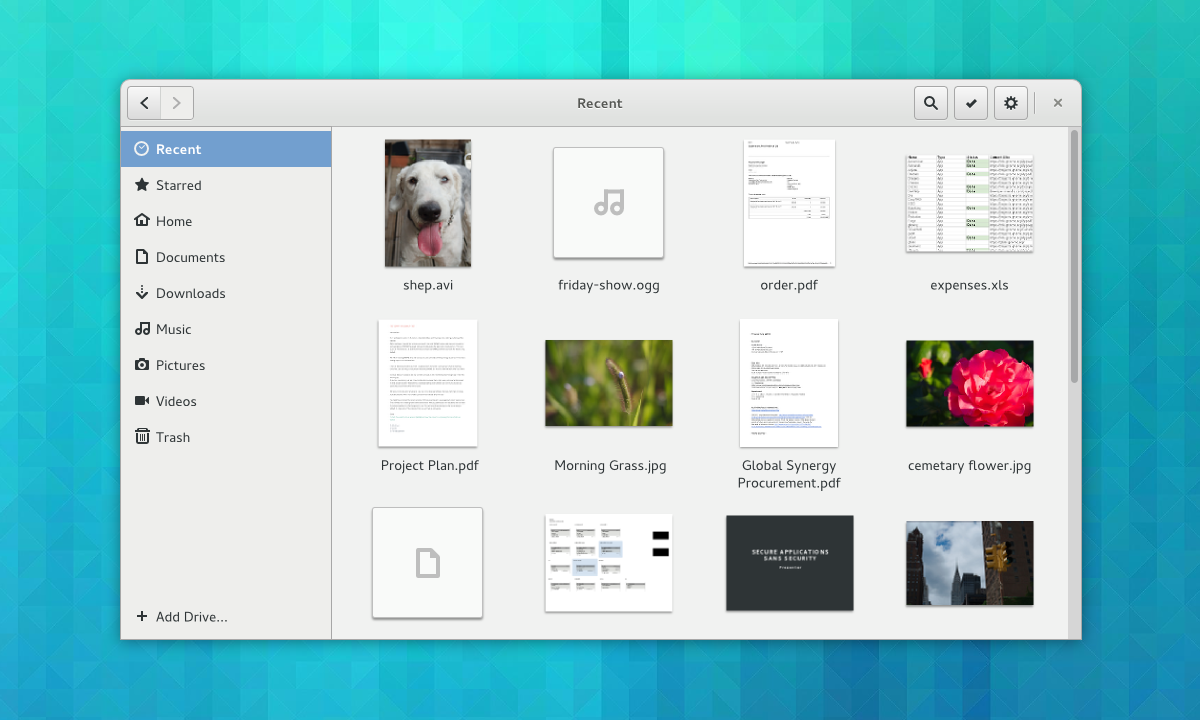

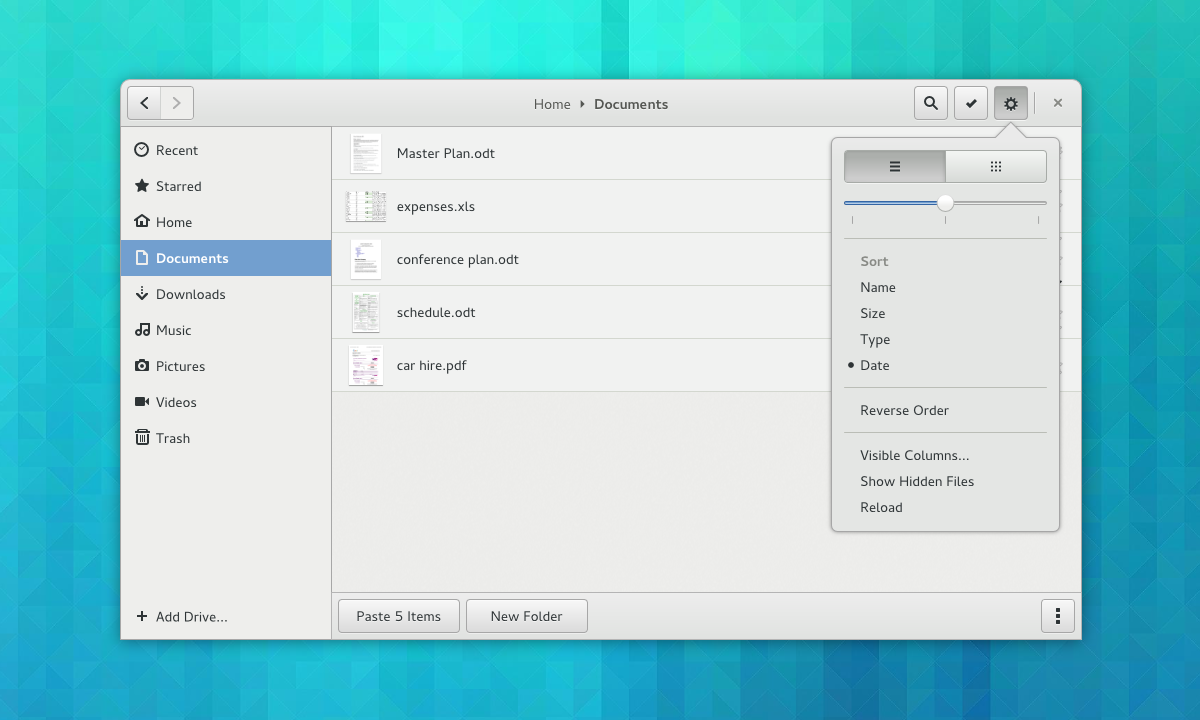

The most important thing in the Files app is, well, your files. If Nautilus is going to provide the kind of experience that we want it to, it needs to do a better job at making your files easy to recognise, look good, and take centre stage. This requires lists and grids that have even spacing, helpful zoom levels, and big, clear thumbnails.

The designs feature new lists and grids, which should hopefully be possible with GTK’s new grid and list widgets. The grids we have in mind will be responsive, so that the content will scale to fit the size and shape of the window (without large spaces between cells or gutters on one side). Lists will feature thumbnails and have separators between rows to aid readability.

The designs also include mockups for an updated view “menu”. This contains all the existing options, except with nicer controls.

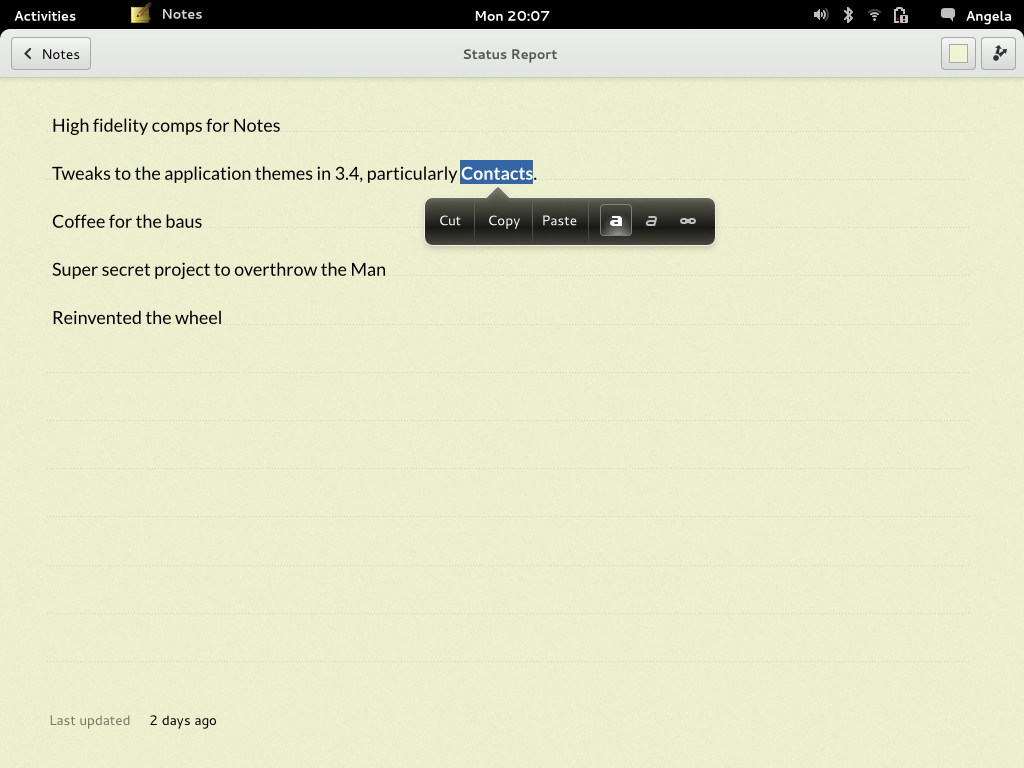

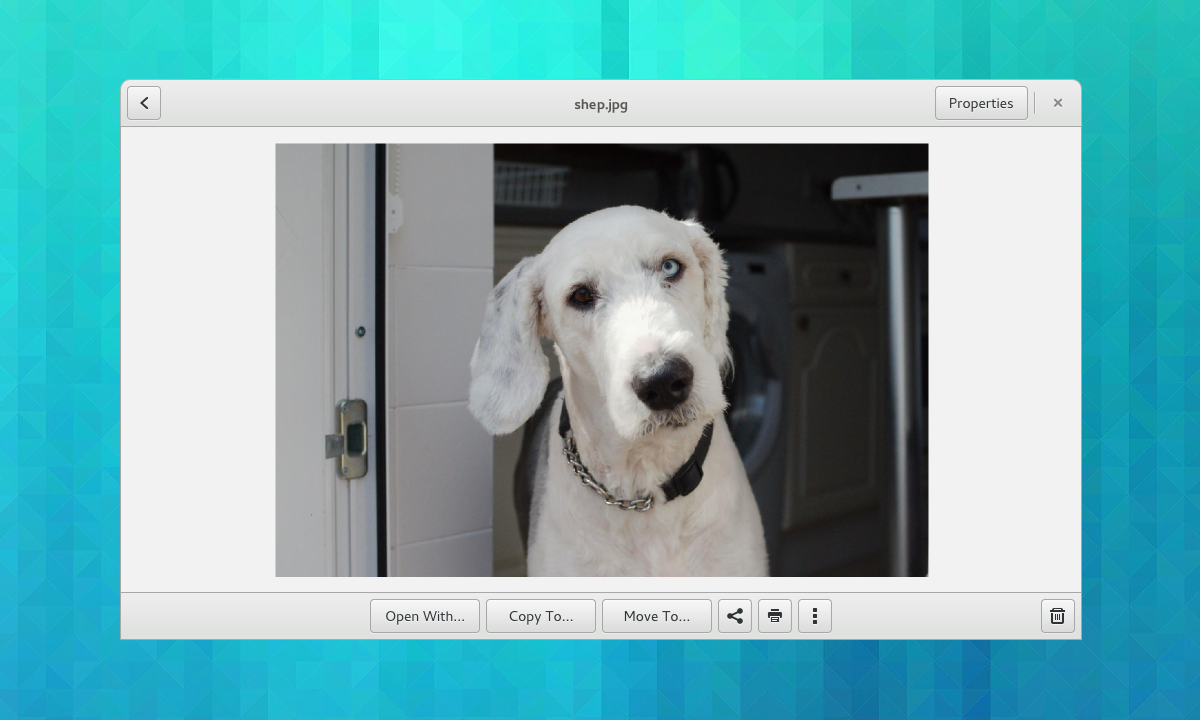

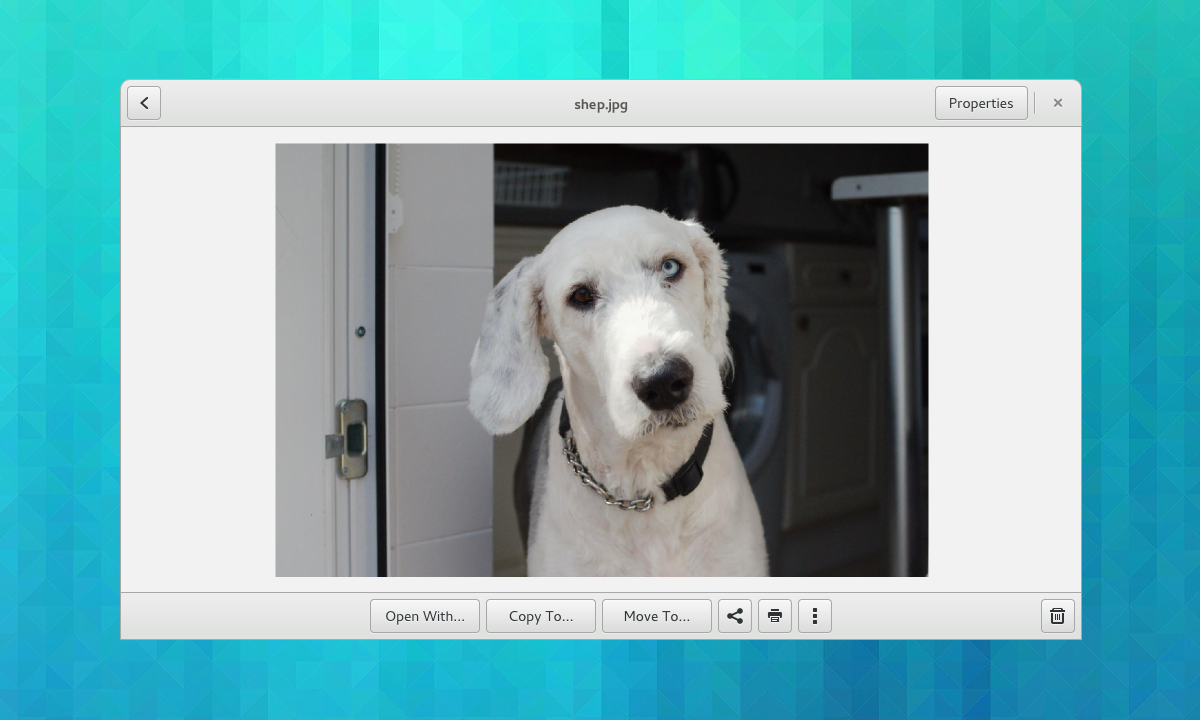

Previews

Being able to inspect the content of a file is often essential to identifying it, such as when you have lots of similar photos, or PDFs with unhelpful file names. Nautilus already has a previewing feature, but it functions as an optional extra and can easily be missed. The new designs make previewing much more central to the browsing experience. They also include actions alongside previews, so that you can quickly act on the file that’s in front of you.

One thing that you can’t see in this mockup – we also want to make it possible to browse between files from the preview – so you can flip back and forth between images or documents in order to compare them.

Generating previews like this may well require new infrastructure. Specifically, it is likely that we will need a new library for generating previews.

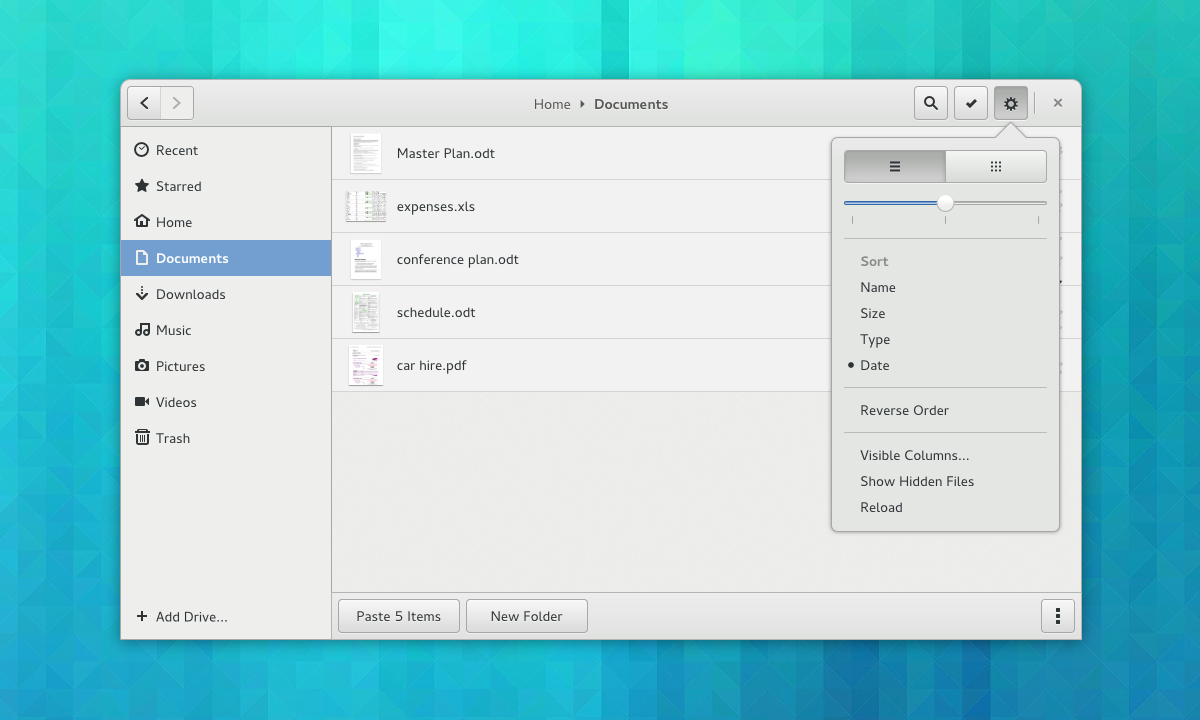

Places

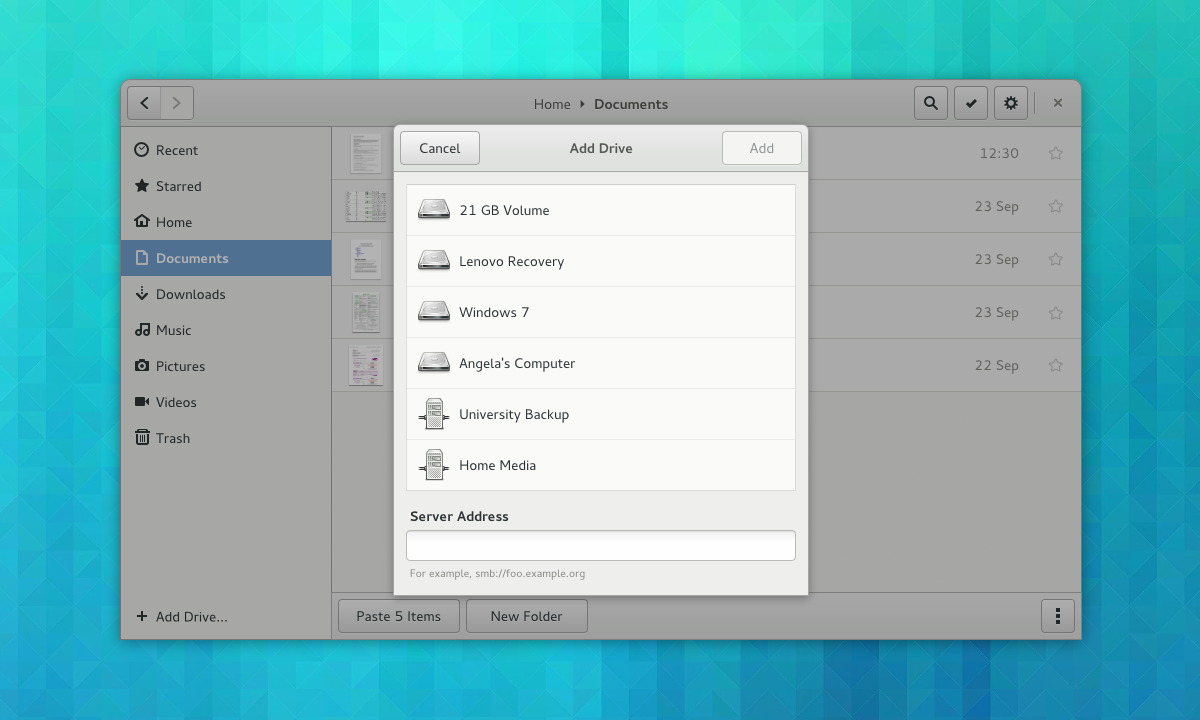

Many of the ideas for the new sidebar design came from the awesome António Fernandes.

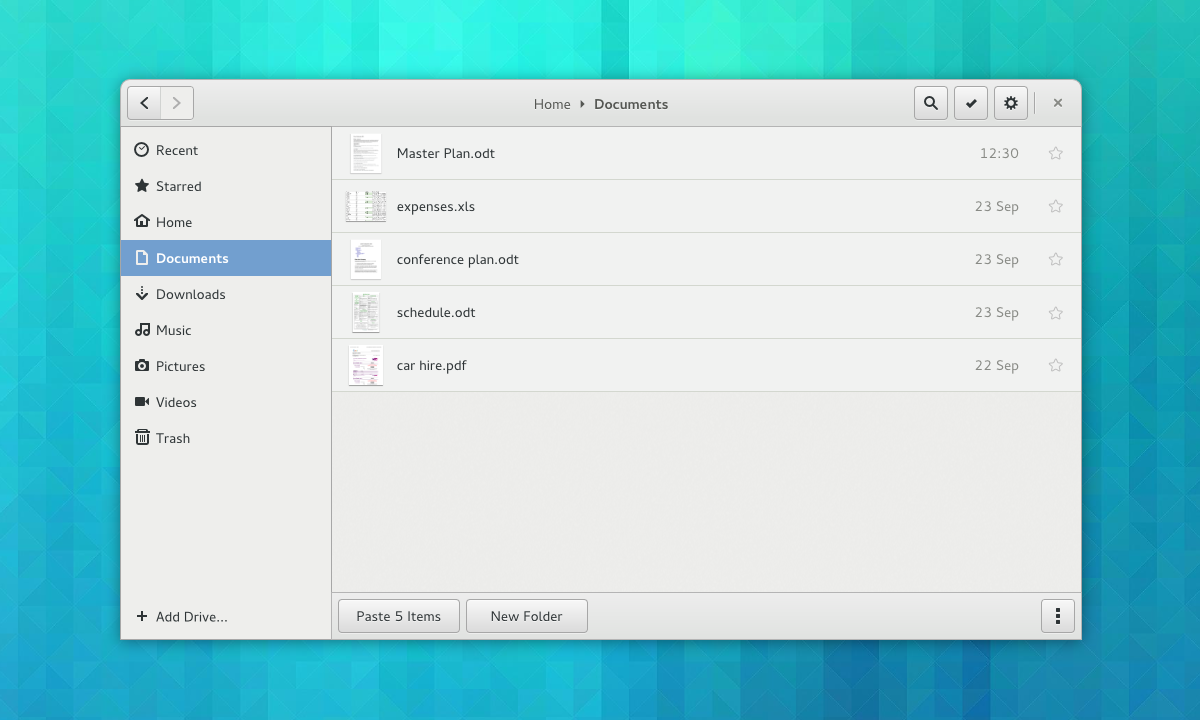

The main objective for the places sidebar is to make it more focused on the things you care about. Right now, the sidebar automatically includes every available volume and drive. This can lead to a cluttered sidebar which contains lots of items that you never use. These often get in the way and distract from the items that you use all the time.

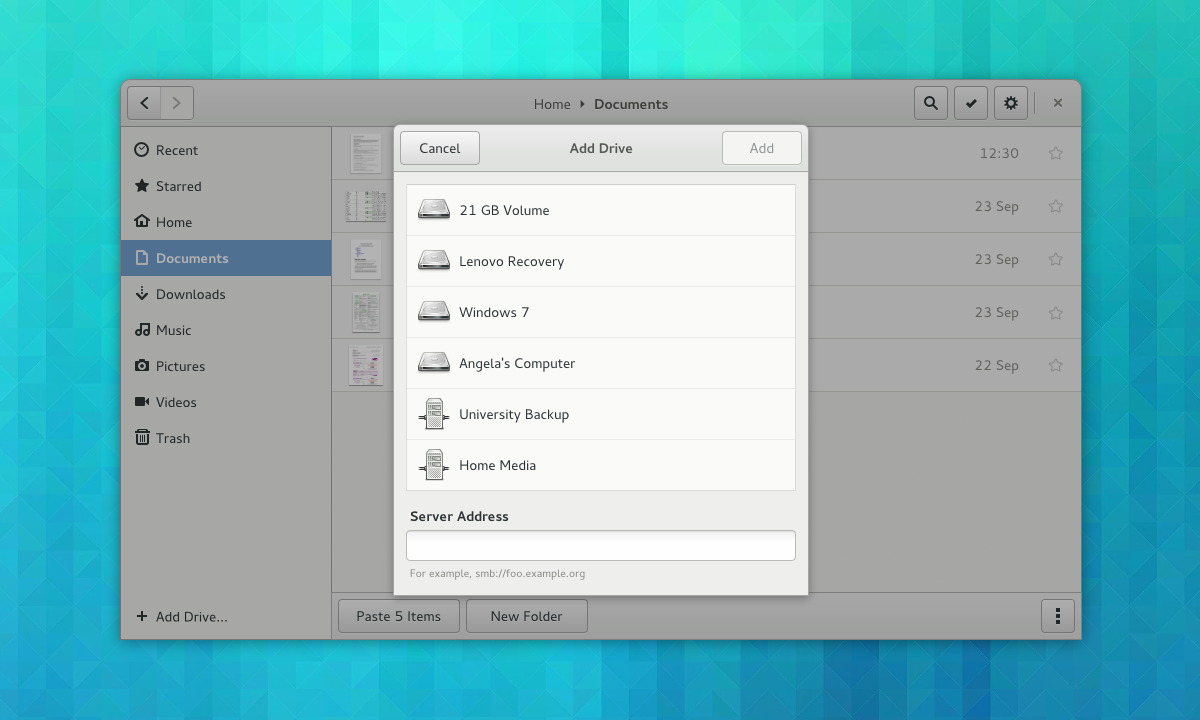

We want to rebalance the sidebar: more things you care about, less things you don’t. To achieve this, we want to make adding drives to the sidebar a manual action. In this way you will be able to customise the sidebar to your needs.

Clarification: manual addition won’t be necessary for removable drives – they will be automatically added to the sidebar as they are now. Also, once an internal volume or remote drive is added, it will persistent even when it’s not mounted.

A new add drive dialog is a key part of the new sidebar design. This will allow you to quickly add both local and remote locations to the sidebar all from the same dialog. It is also an attempt to clean up the various network browsing features that are currently available in Nautilus, and consolidate these features into one place.

The reimagined sidebar also contains a new feature which will be really handy: starred files. Being able to mark items that you want to keep track of is such as obvious feature, and I’m sure it will be useful to many people. In UI terms it’s a fairly simple thing to do.

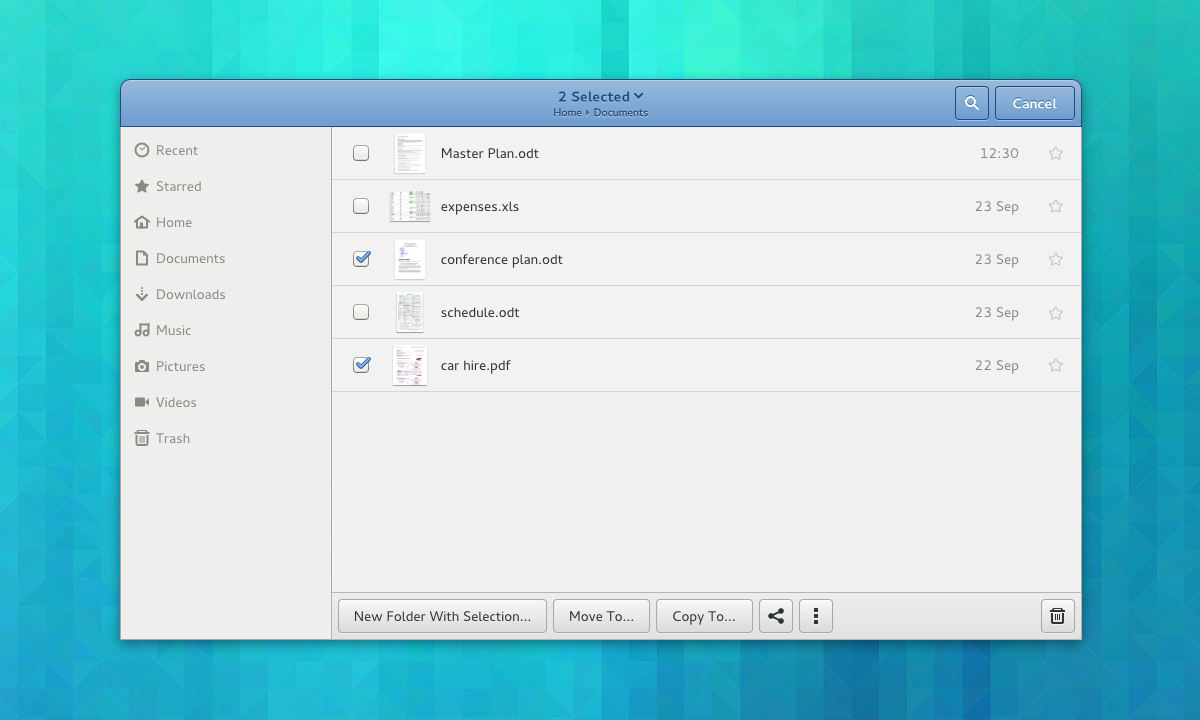

Selections

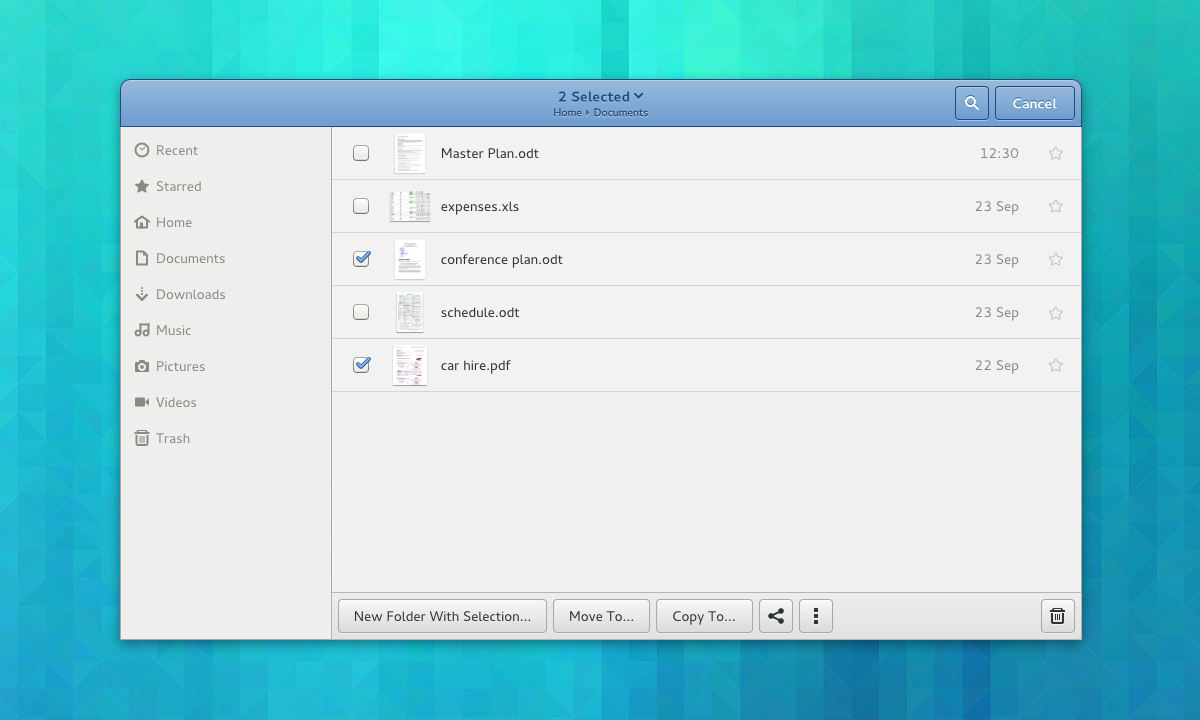

Selection mode is a design pattern that we’re using extensively in the other GNOME 3 applications. It’s nice because it makes contextual actions much more discoverable. It also allows us to use single click (rather than the undiscoverable and inconsistent double-click) throughout.

The best way to think of the use of selection mode here is as a discoverable context menu. Existing methods of selecting multiple items, like holding ctrl and shift in combination with the mouse button, will continue to work.

Added Discoverability

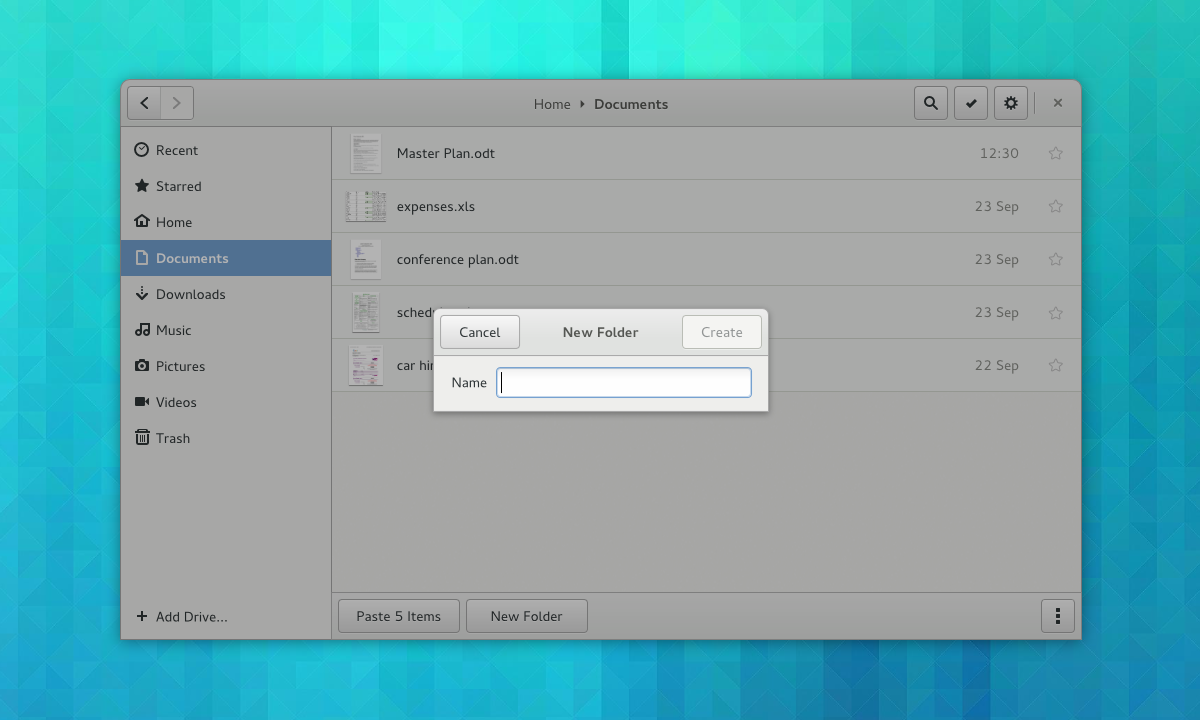

It’s amazing how many undiscoverable conventions that we acclimatise ourselves to, and an old app like Nautilus has a lot of them. At some point in the past, we all learned to double-click to open, to press return to finish naming a new folder, or that Ctrl+V pastes content into the current location. All of this is totally unobvious to new users, of course, and there can be embarrassing moments when you watch someone use an app like Nautilus for the first time.

The new Nautilus designs bring a lot of hidden functionality to the surface, and they make an effort not to assume prior knowledge. Much of the functionality that is currently hidden in the background has been brought to the surface: there are visible buttons for common tasks like pasting items or creating folders, for example. Simple things – like using a dialog for creating new folders – are designed to eliminate basic usability bugs.

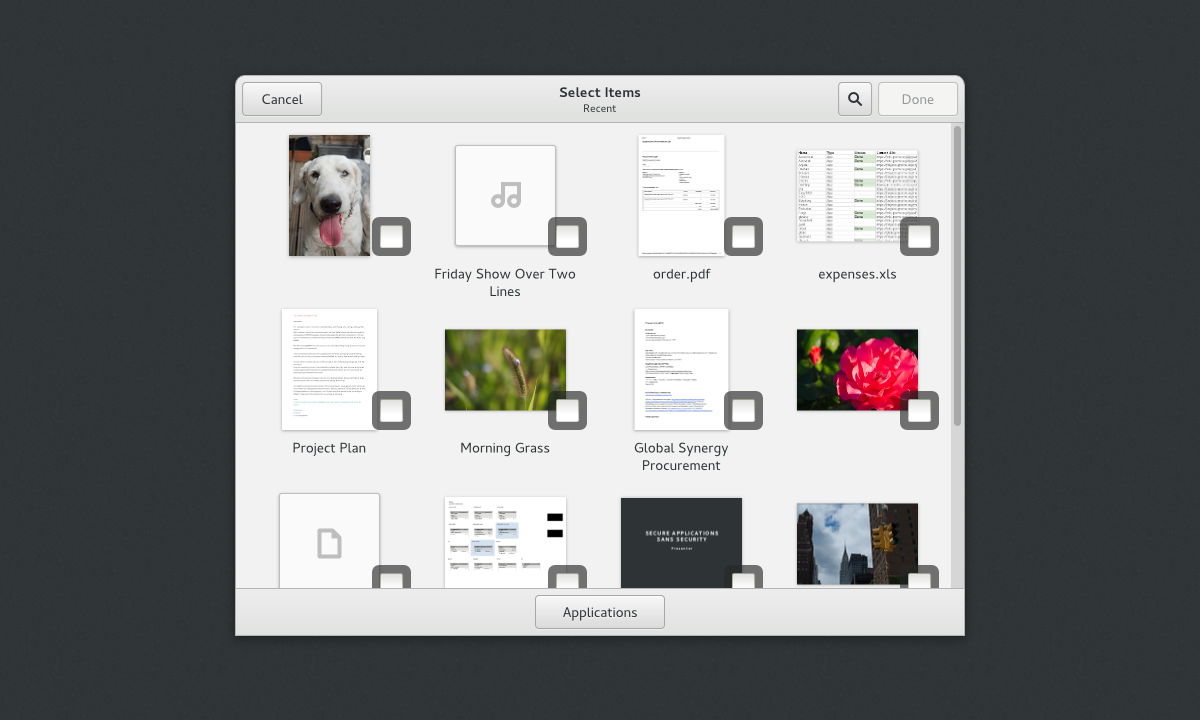

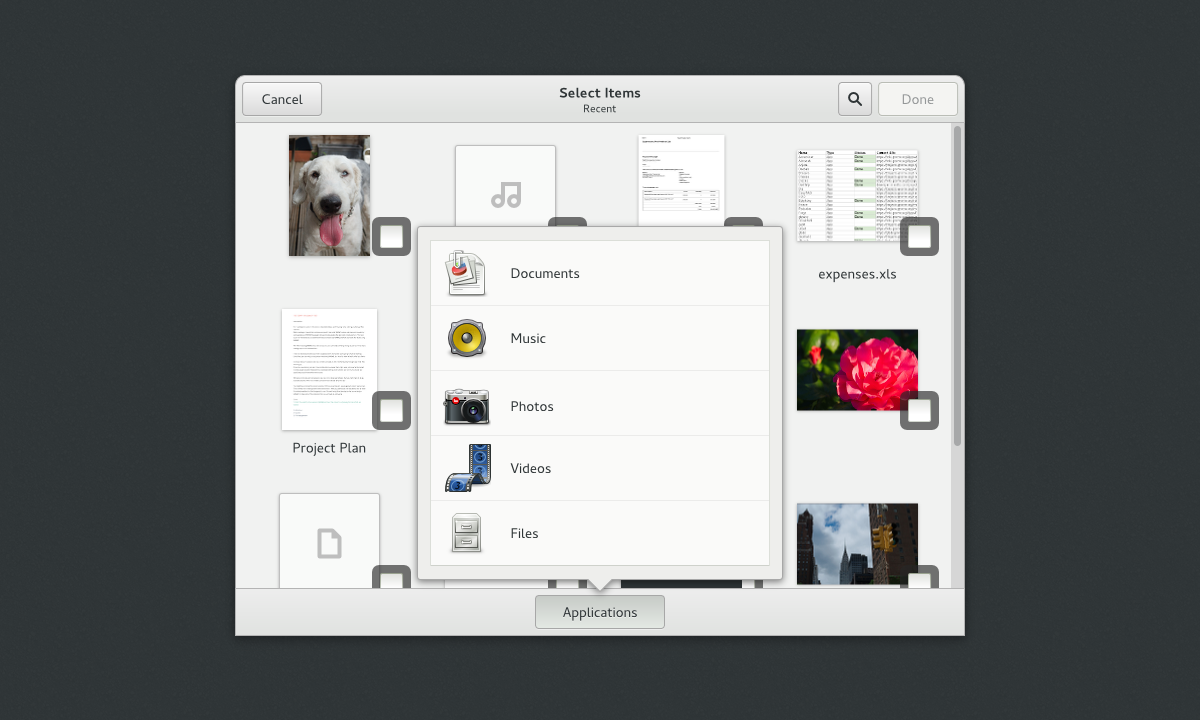

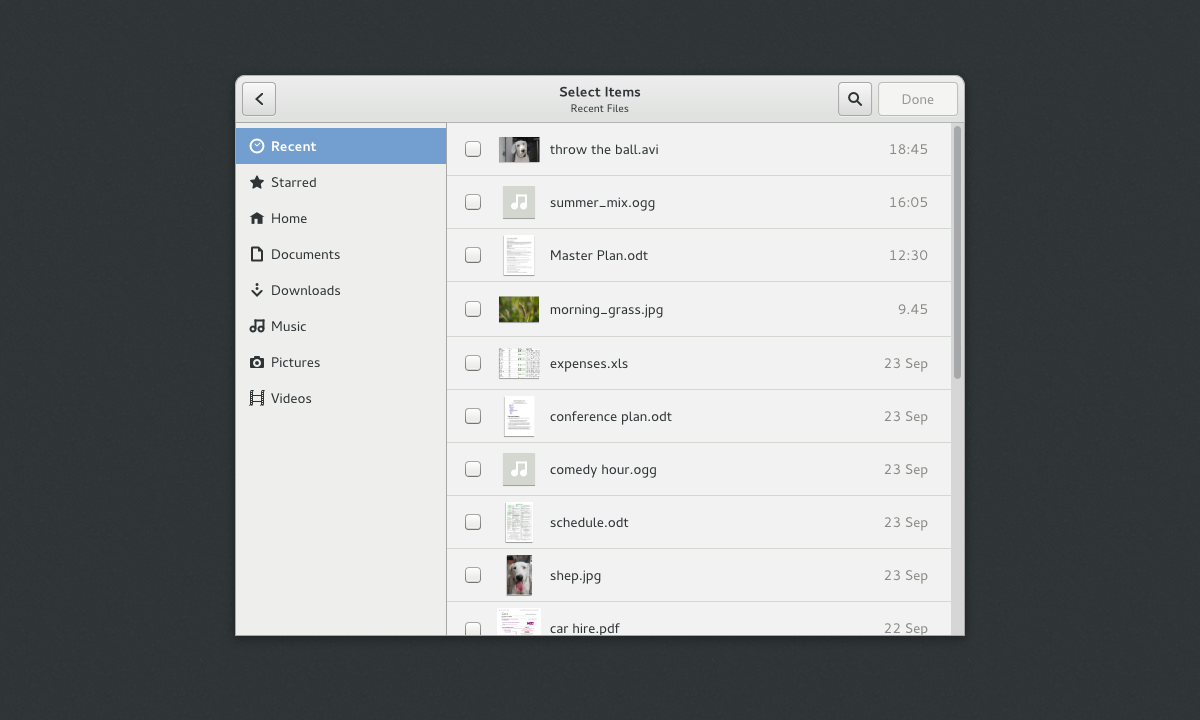

Content Selection

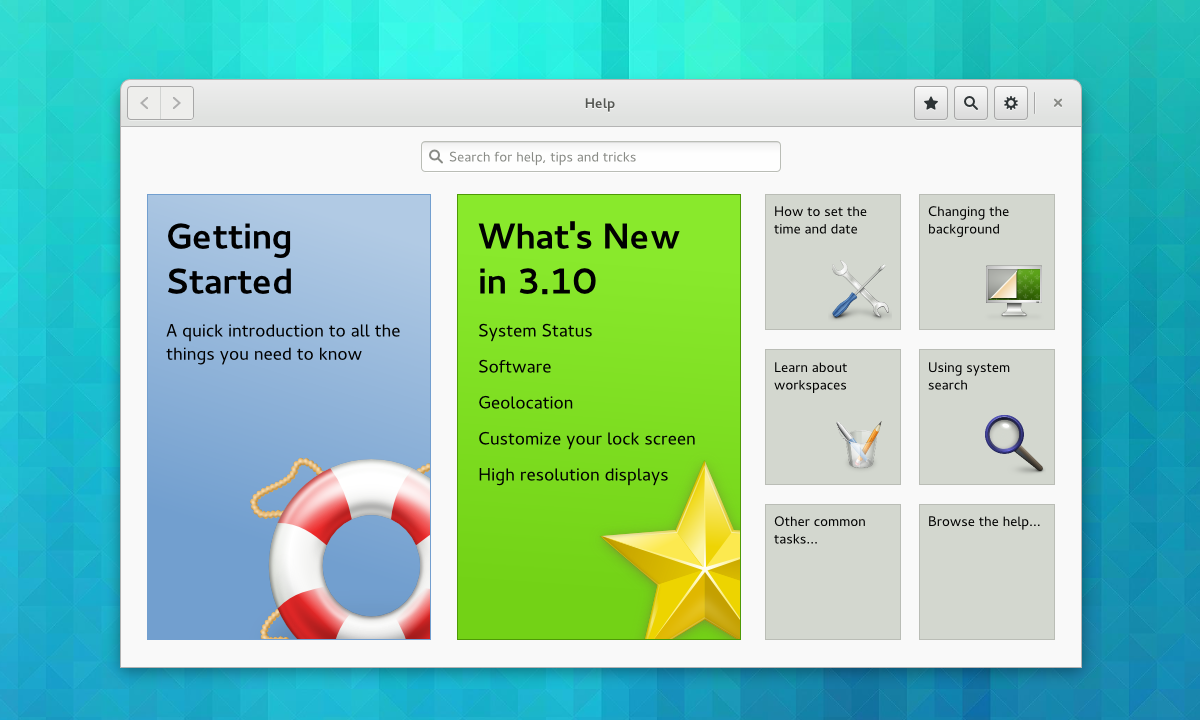

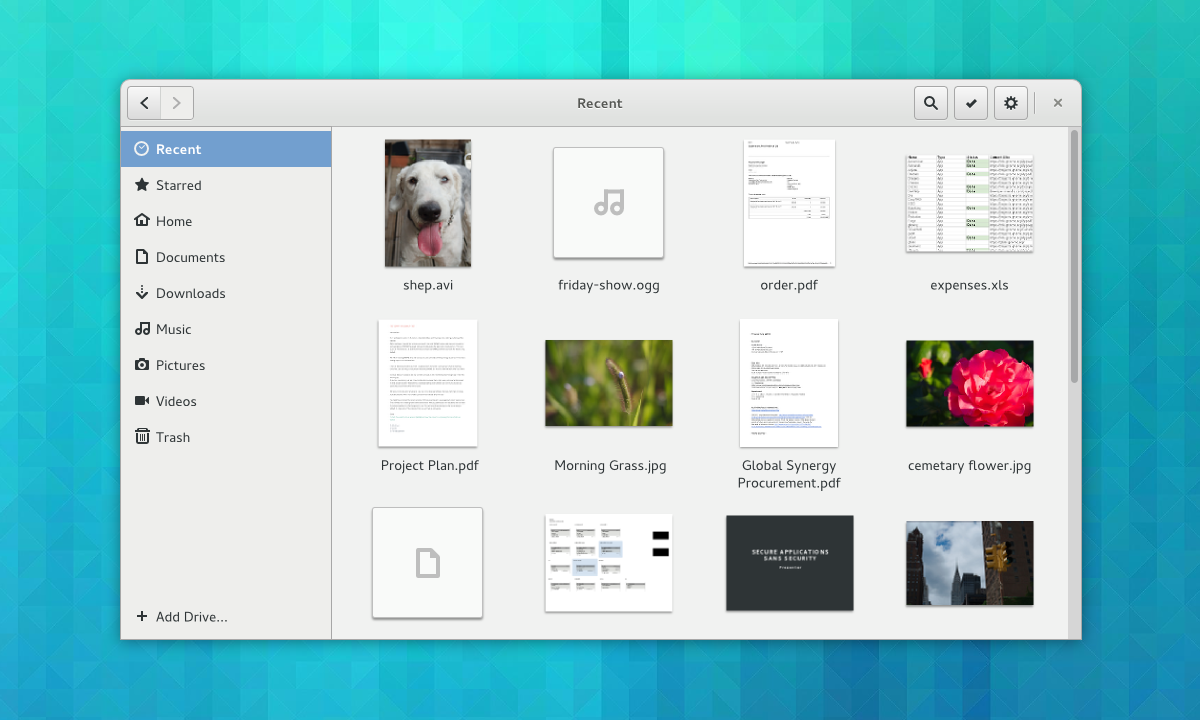

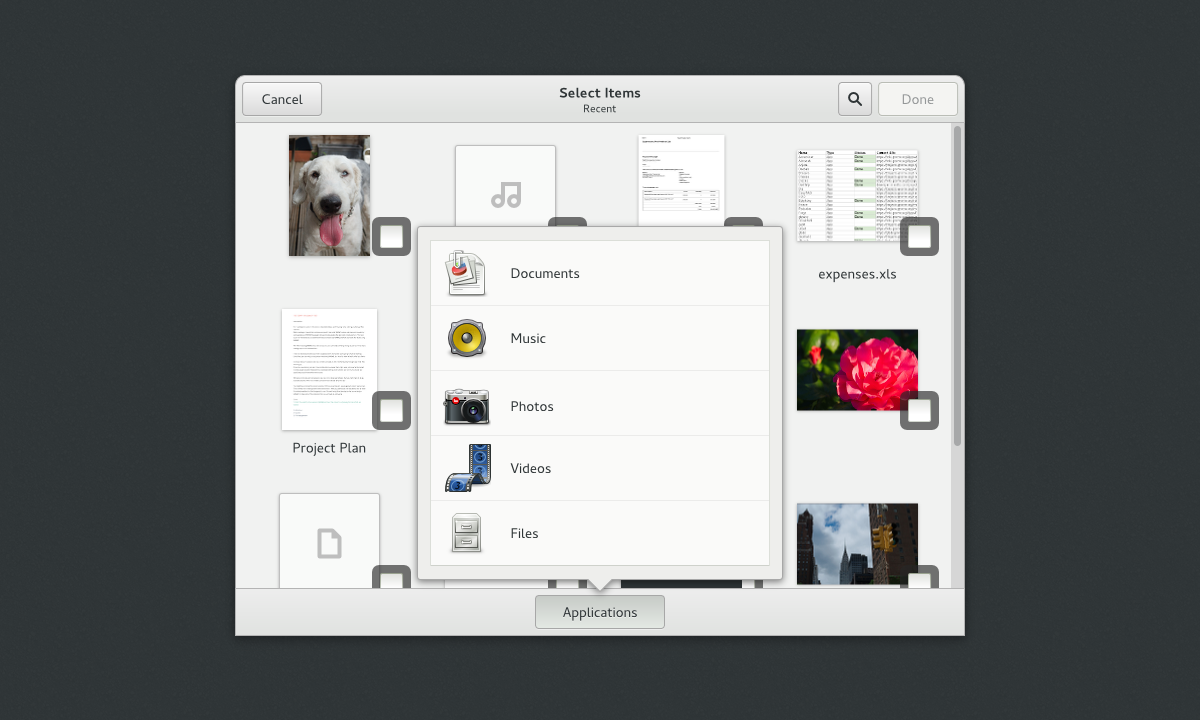

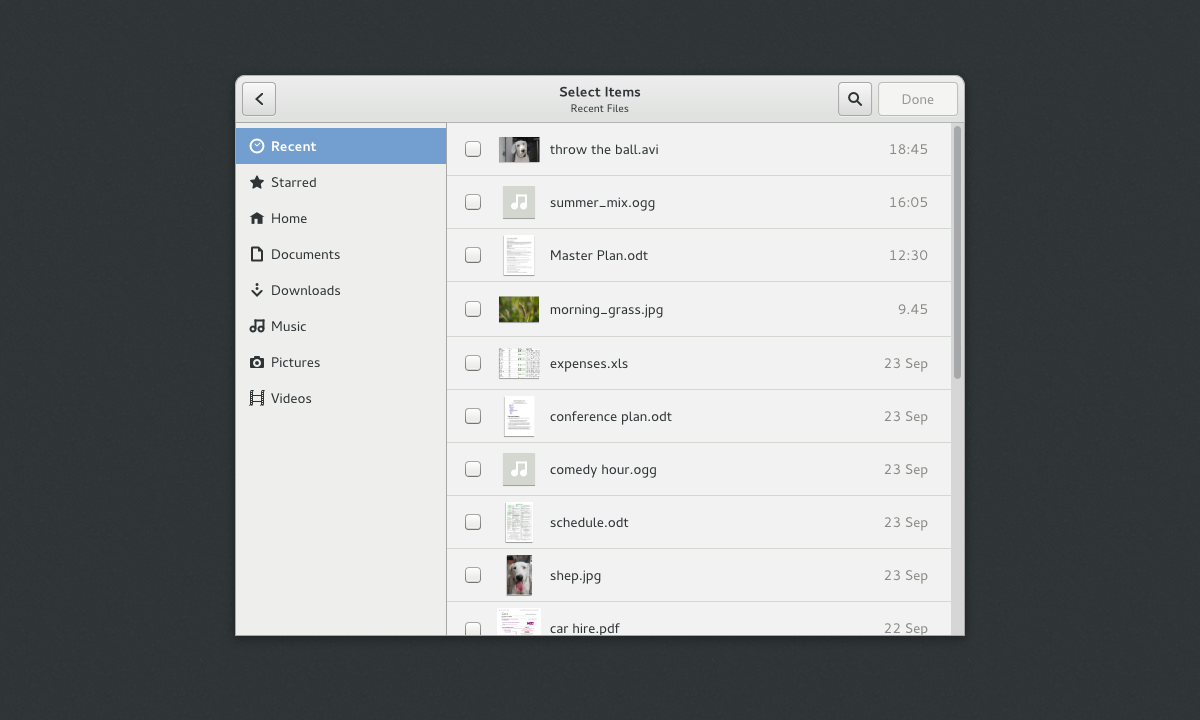

Finally, this brings us back to content selection. A next generation replacement for the existing file selection dialog is something that has been mooted for a long while. To make it happen, a number of other long-term initiatives need to come together: the new set of content selection applications needs to come together, and we need the previewing library that I mentioned about above.

This latest round of Nautilus design work was in part motivated to keep these content selection plans moving forward, and the Nautilus designs were developed at the same time as a new set of content selection mockups. This is to ensure that the file browser keeps in step with our longer term plans.

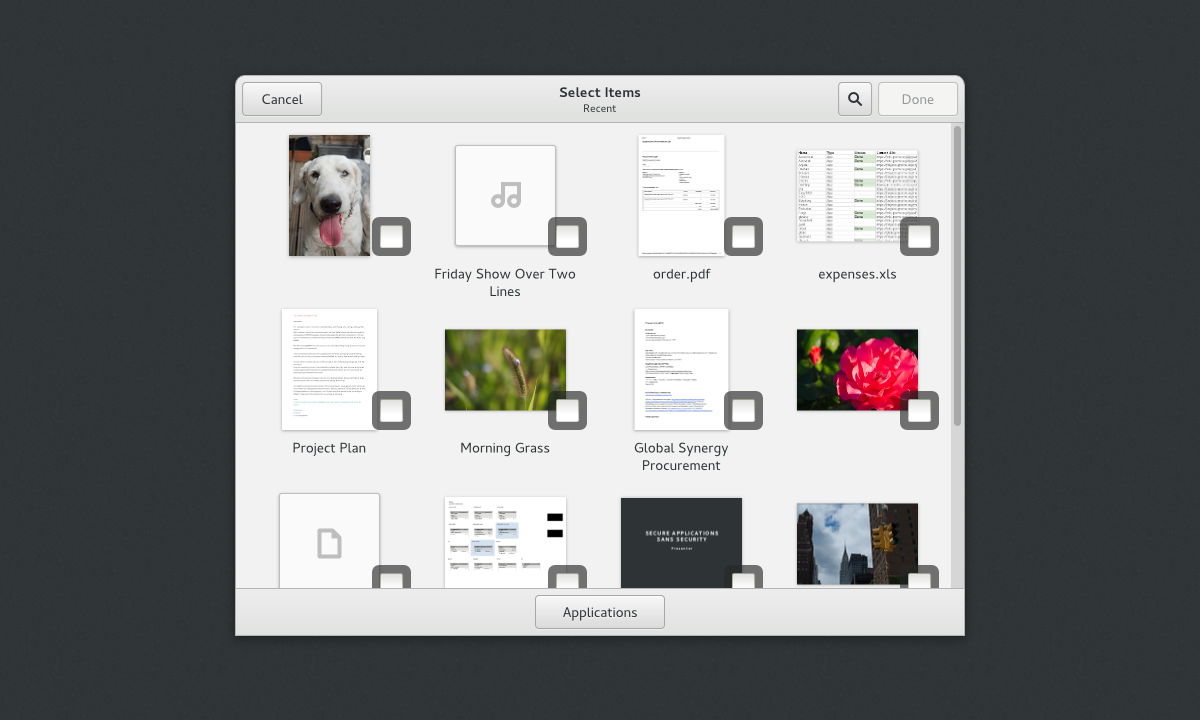

The new content chooser is designed to allow you to select content items from a range of sources. These can be local files or content items that are stored in the cloud. This is where the various new content applications come in – each one is designed to act as a cloud-based content provider. With this approach, you should be able to use the Photos app to select images from Flickr, for example.

The initial view provides a grid of recently used items. After that, you can choose a particular content provider. Content apps can then present their own content. Notice that, after opting to view files, the familiar places sidebar from Files slides in.

What You Can Do

If you want to help us make these designs a reality, there are many things that we need help with, both large and small. I will be busy turning the designs into bug reports over the coming weeks, and will be keeping the design page up to date as the plans take shape. You can subscribe to the page if you want to follow what’s happening. Otherwise, just get in touch. We would love to hear from you, even if you are just interested.

Comments on this post are now closed. Thanks for all the fantastic feedback.