We just landed the largest refactor to Builder since it’s inception. Somewhere around 100,000 lines of code where touched which is substantial for a single development cycle. I wrote a few tools to help us do that work, because that’s really the only way to do such a large refactor.

Not only does the refactor make things easier for us to maintain but it will make things easier for contributors to write new plugins. In a future blog post I’ll cover some of the new design that makes it possible.

Let’s take a look at some of the changes in Builder for 3.32 as users will see them.

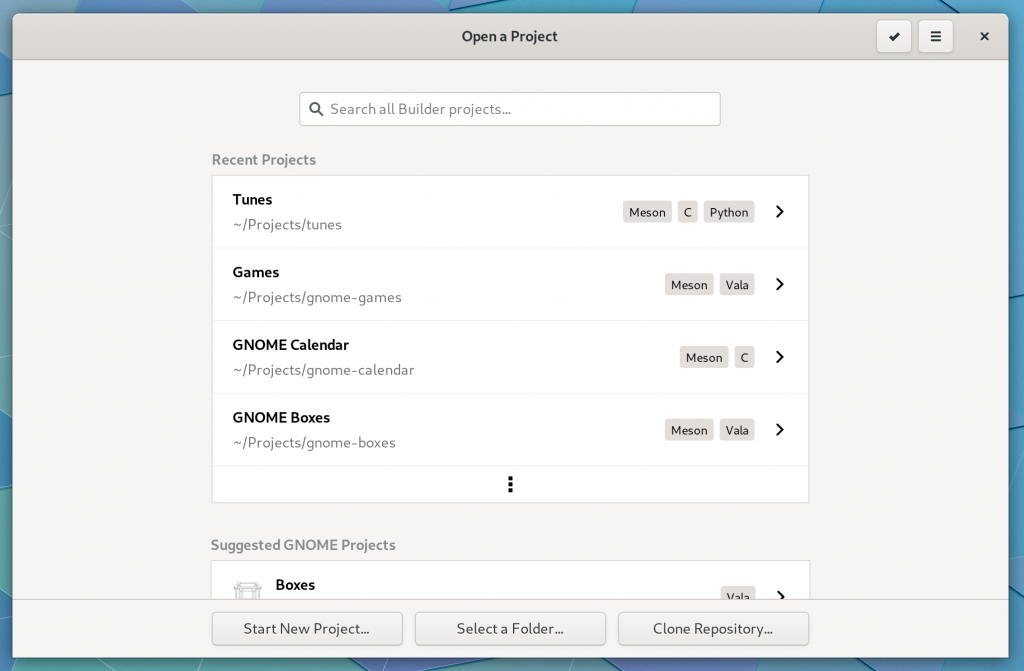

First we have the greeter. It looks similar as before, although with a design refresh. But from a code standpoint, it no longer shares it’s windowing with the project workspace. Taking this approach allowed us to simplify Builder’s code and allows for a new feature you’ll see later.

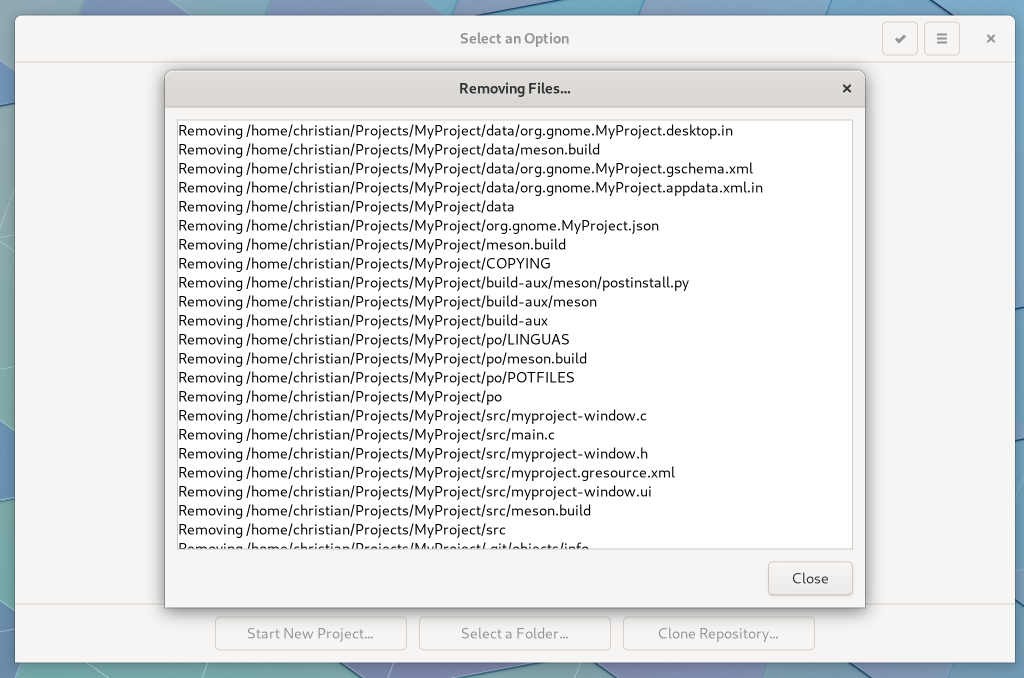

Builder now gives some feedback about what files were removed when cleaning up old projects.

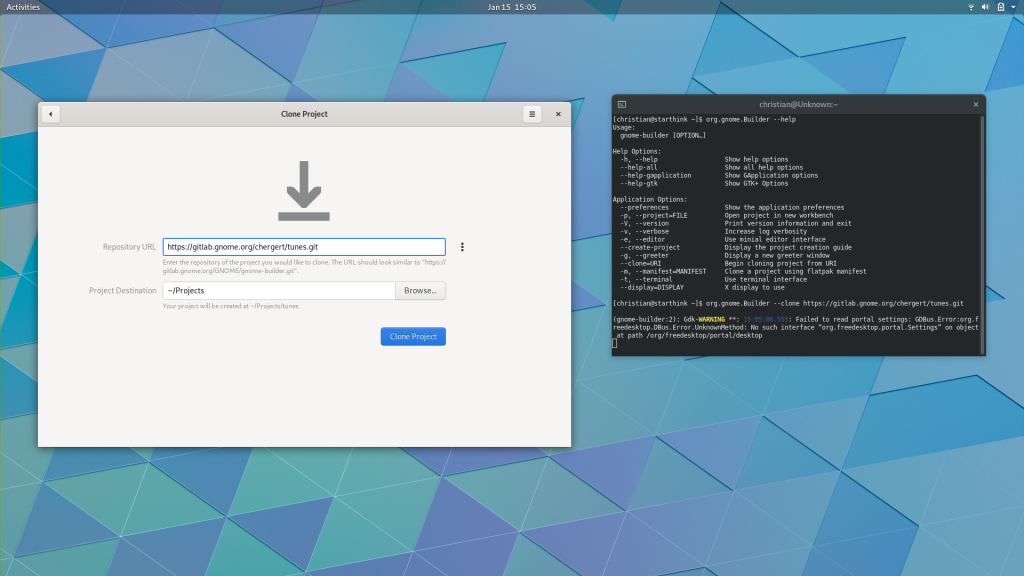

Builder gained support for more command-line options which can prove useful in simplifying your applications setup procedure. For example, you can run gnome-builder --clone https://gitlab.gnome.org/GNOME/gnome-builder.git to be taken directly to the clone dialog for a given URL.

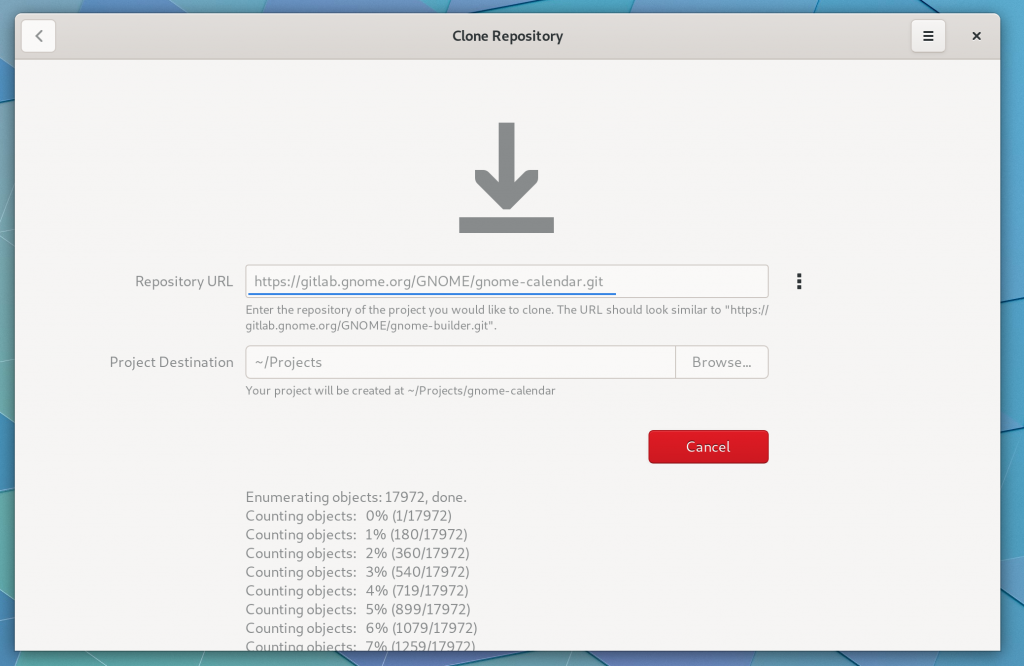

The clone activity provides various messaging in case you need to debug some issues during the transfer. I may hide this behind a revealer by default, I haven’t decided yet.

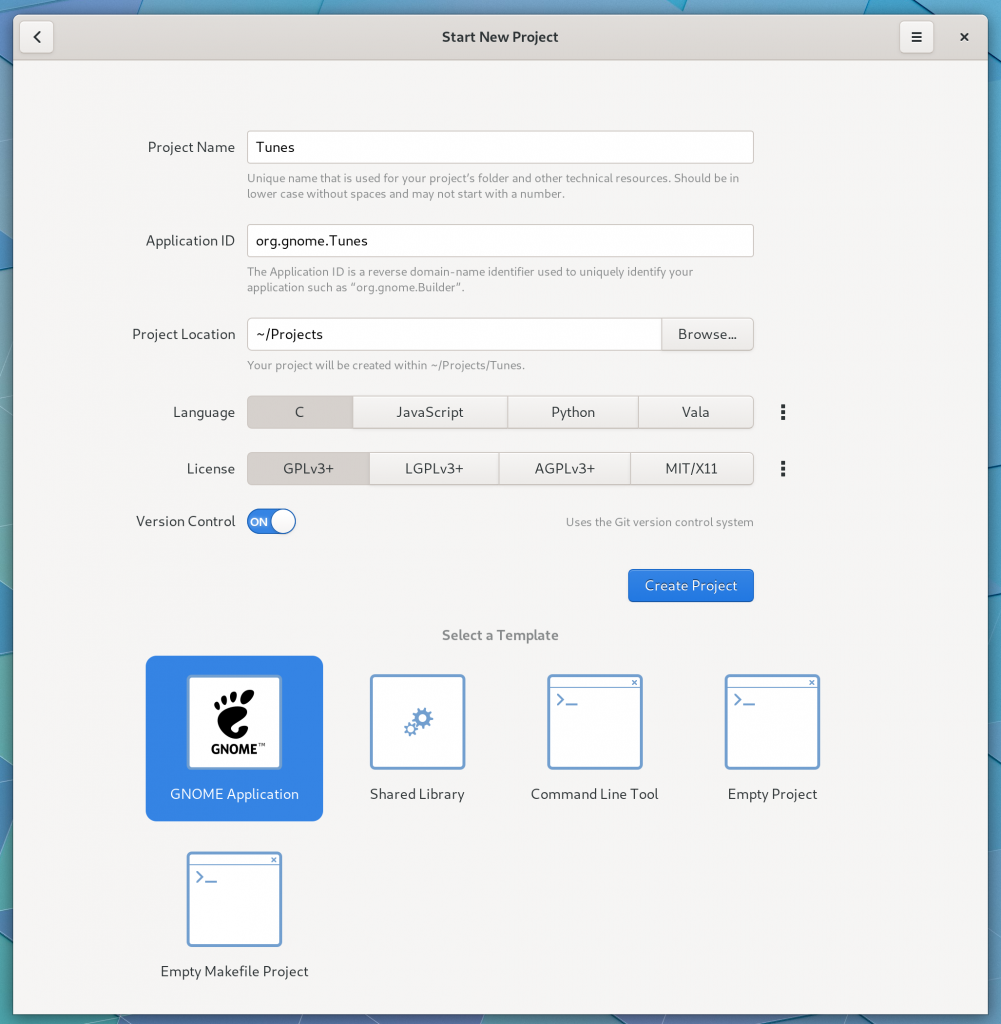

Creating a new project allows specifying an application-id, which is good form for desktop applications.

We also moved the “Continue” button out of the header bar and placed it alongside content since a number of users had difficulty there.

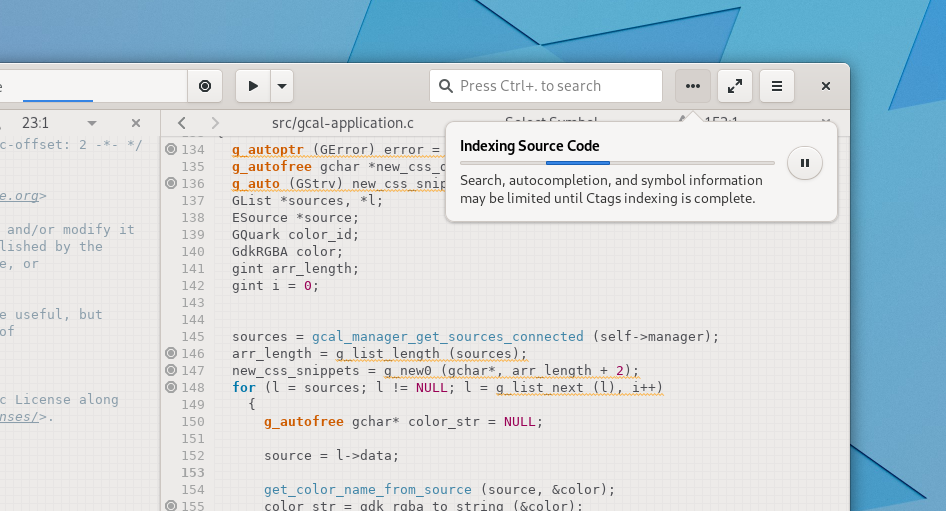

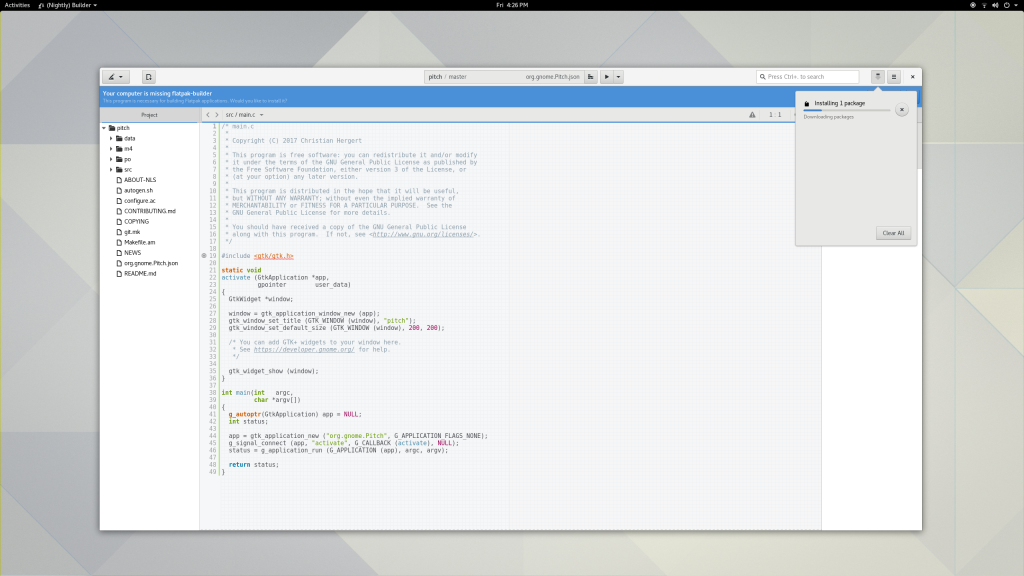

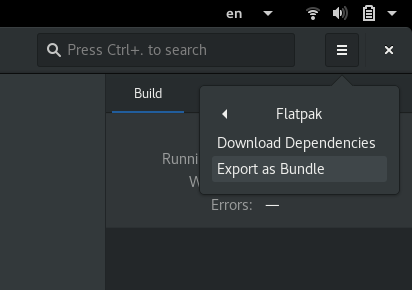

The “omni-bar” (center of header bar) has gained support for moving through notifications when multiple are present. It can also display buttons and operational progress for rich notifications.

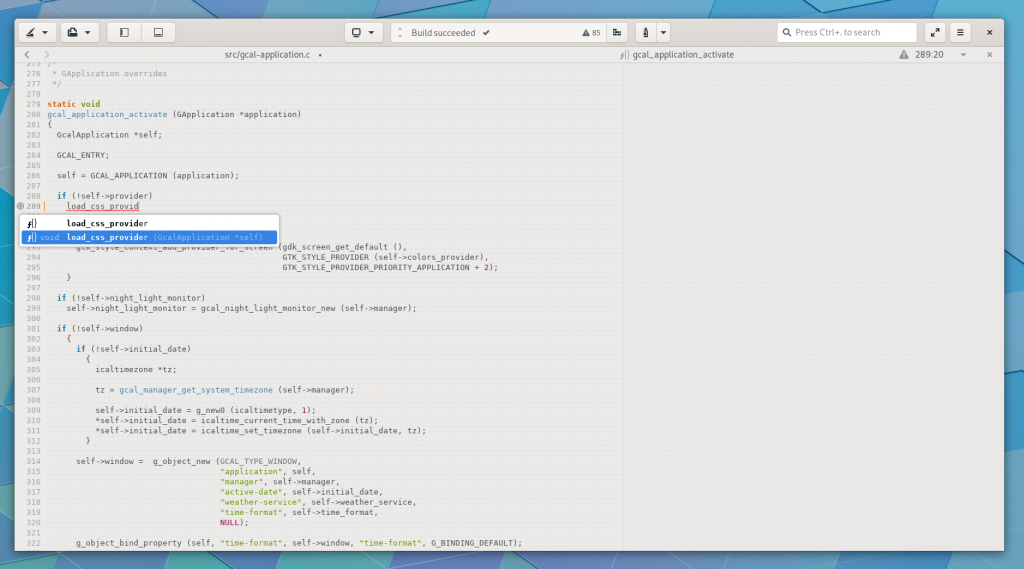

Completion hasn’t changed much since last cycle. Still there, still works.

Notifications that support progress can also be viewed from our progress popover similar to Nautilus and Epiphany. Getting that circle-pause-button aligned correctly was far more troublesome than you’d imagine.

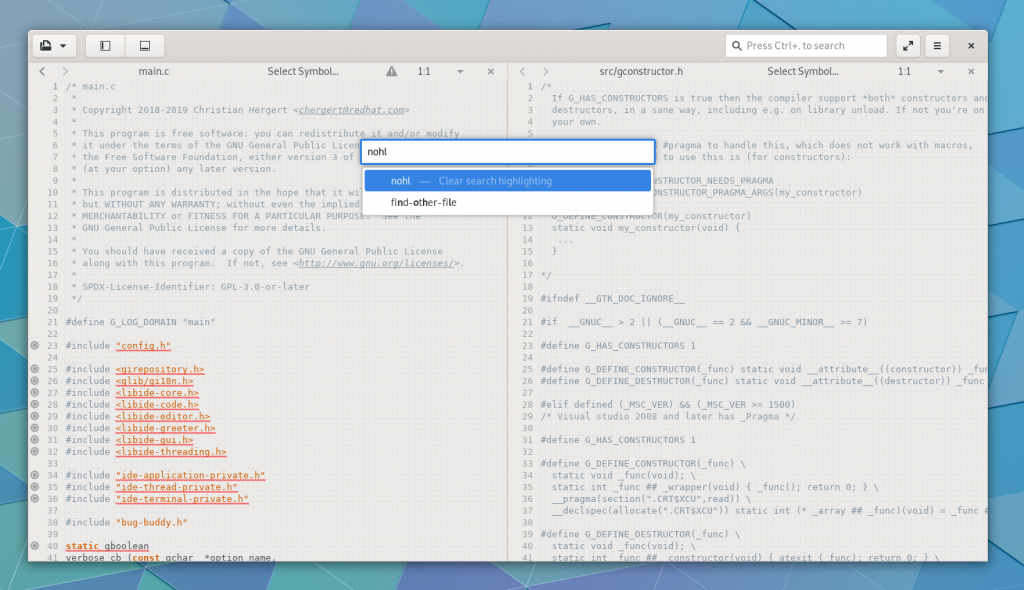

The command-bar has been extracted from the bottom of the screen into a more prominent position. I do expect some iteration on design over the next cycle. I’ve also considered merging it into the global search, but I’m still undecided.

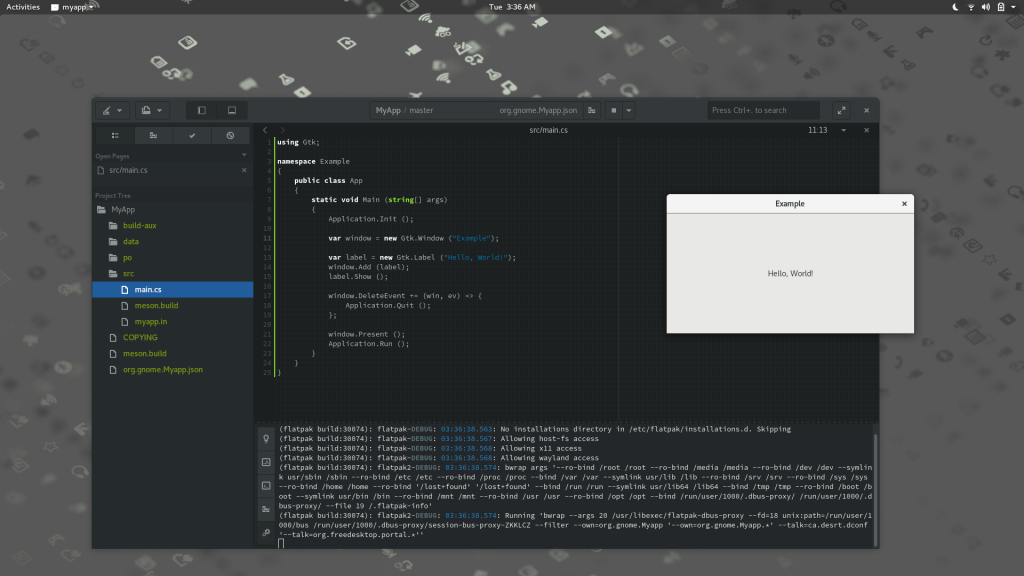

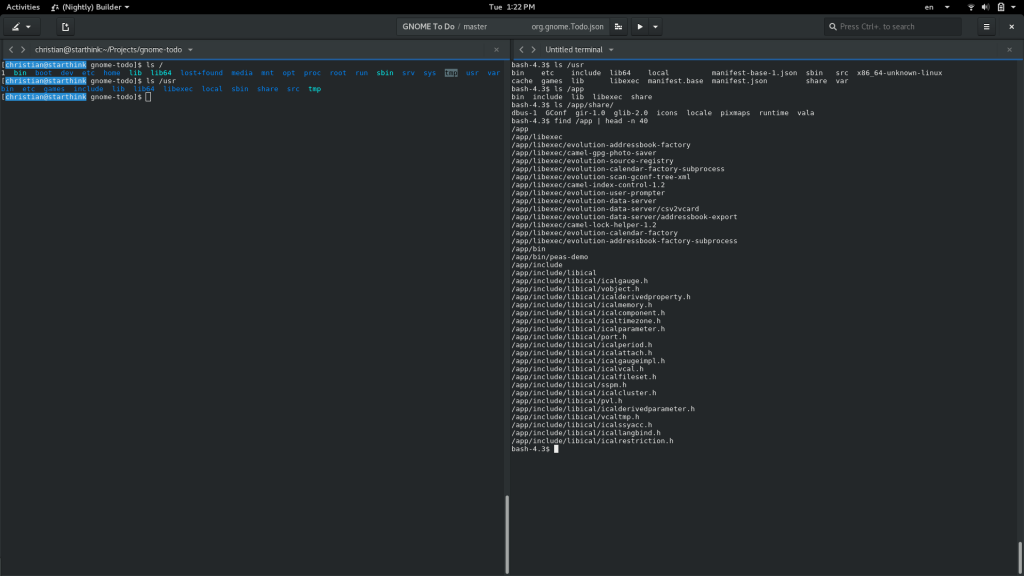

Also on display is the new project-less mode. If you open Builder for a specific file via Nautilus or gnome-builder foo.c you’ll get this mode. It doesn’t have access to the foundry, however. (The foundry contains build management and other project-based features).

The refactoring not only allowed for project-less mode but also basic multi-monitor support. You can now open a new workspace window and place it on another monitor. This can be helpful for headers, documentation, or other references.

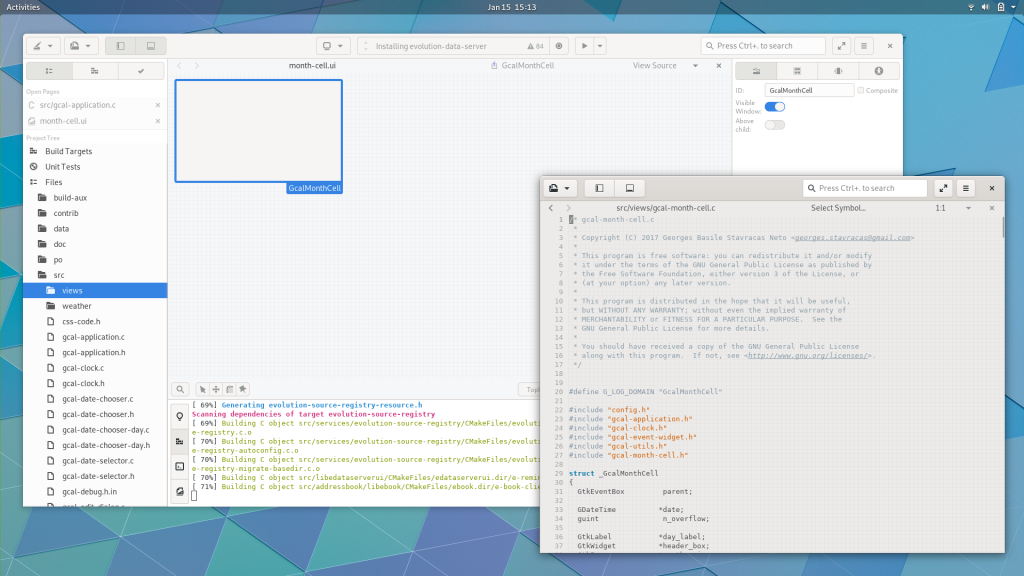

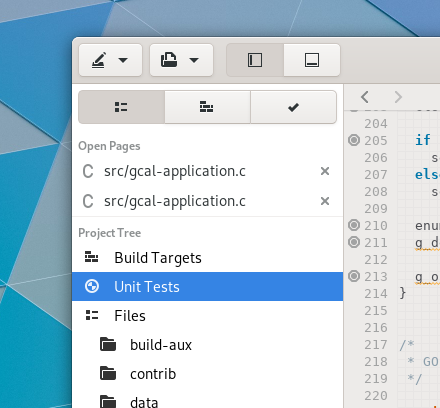

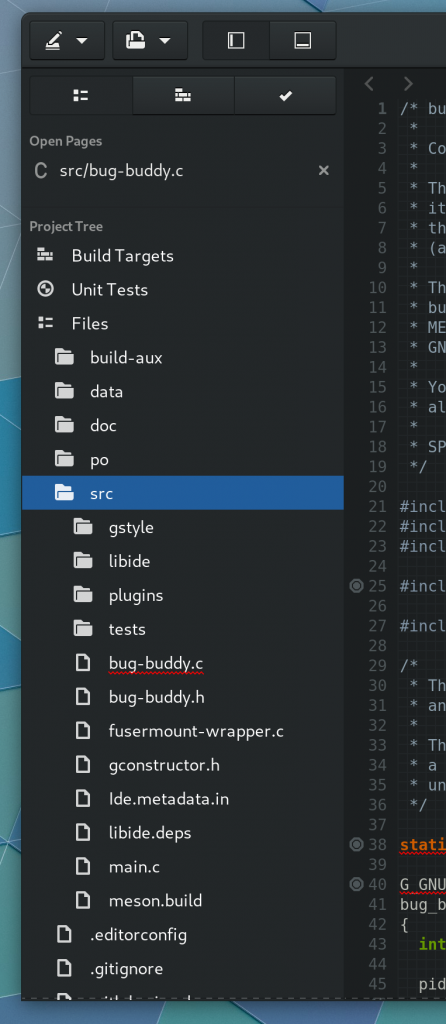

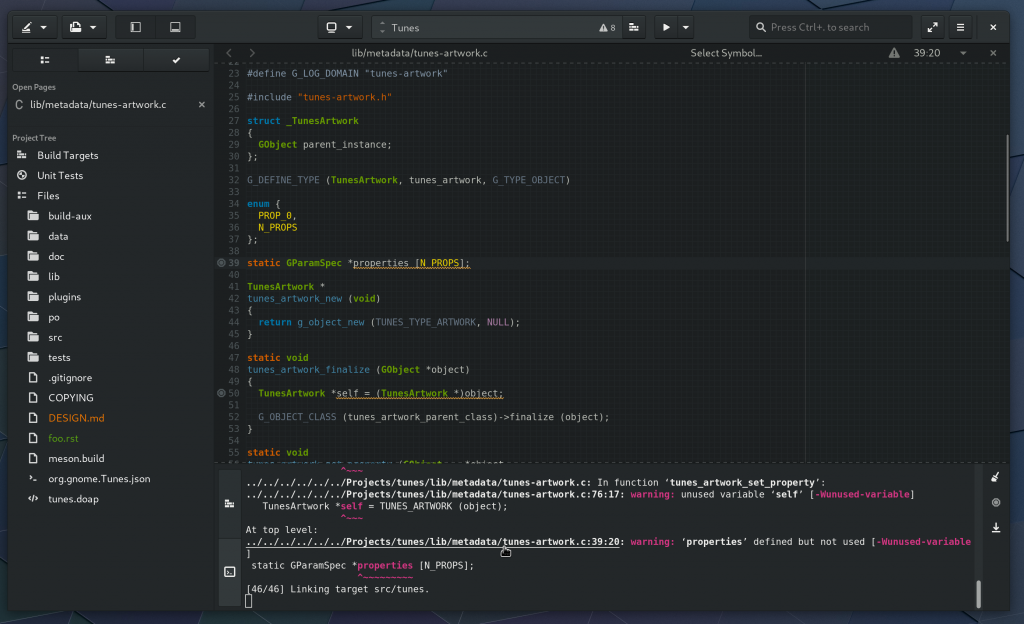

The project tree has support for unit tests and build targets in addition to files.

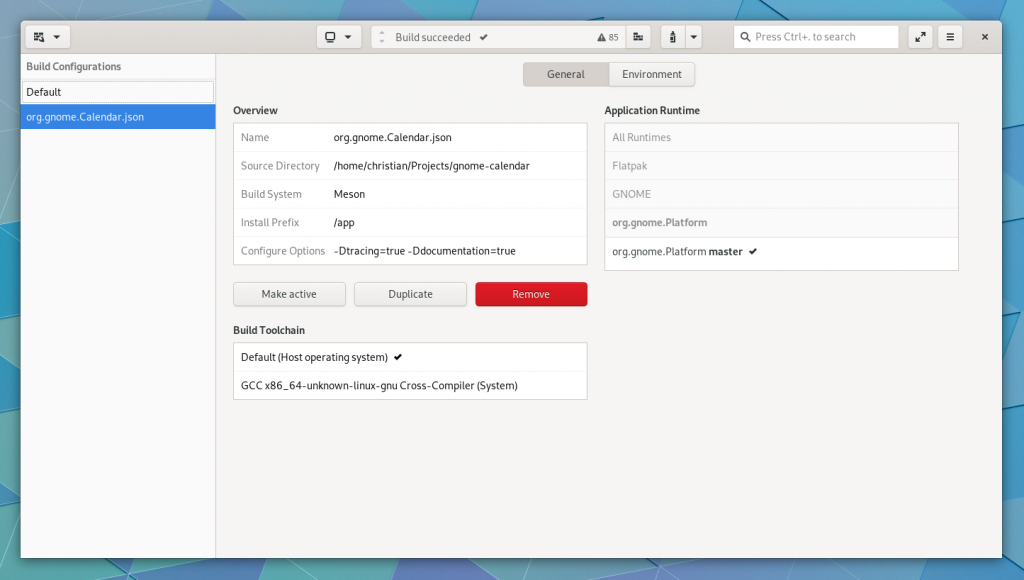

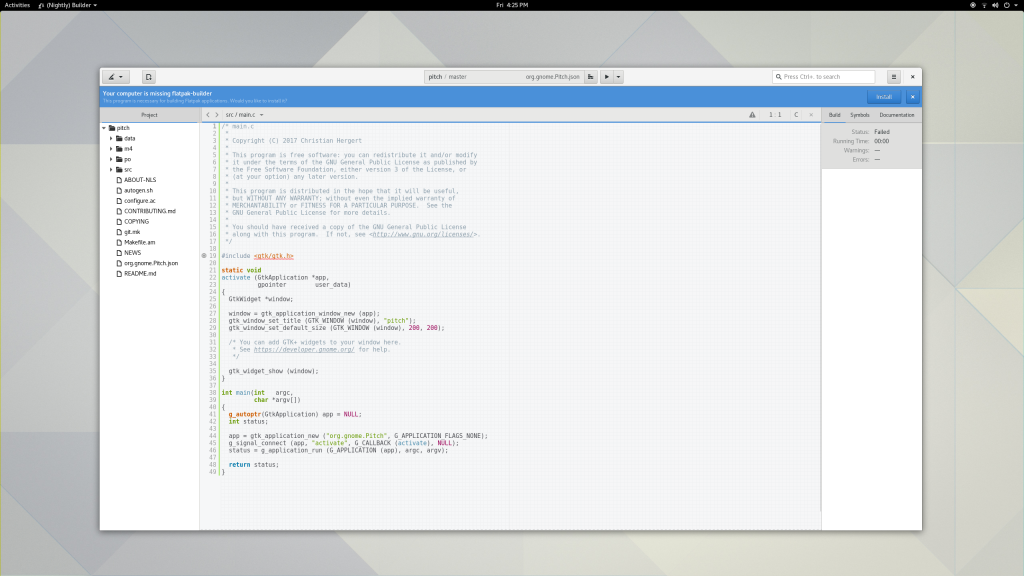

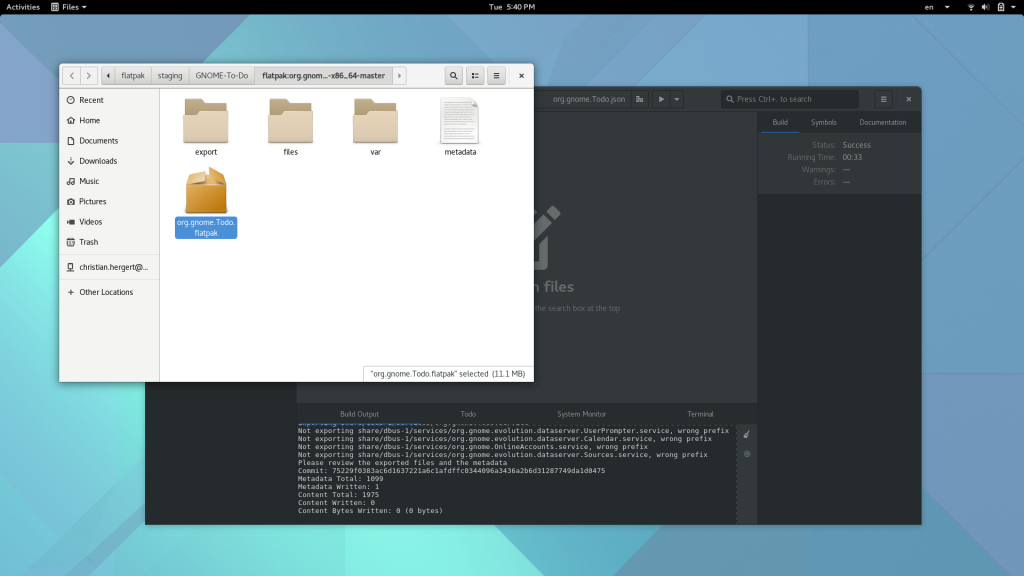

Build Preferences has been rebuilt to allow plugins to extend the view. That means we’ll be able to add features like toggle buttons for meson_options.txt or toggling various clang/gcc sanitizers from the Meson plugin.

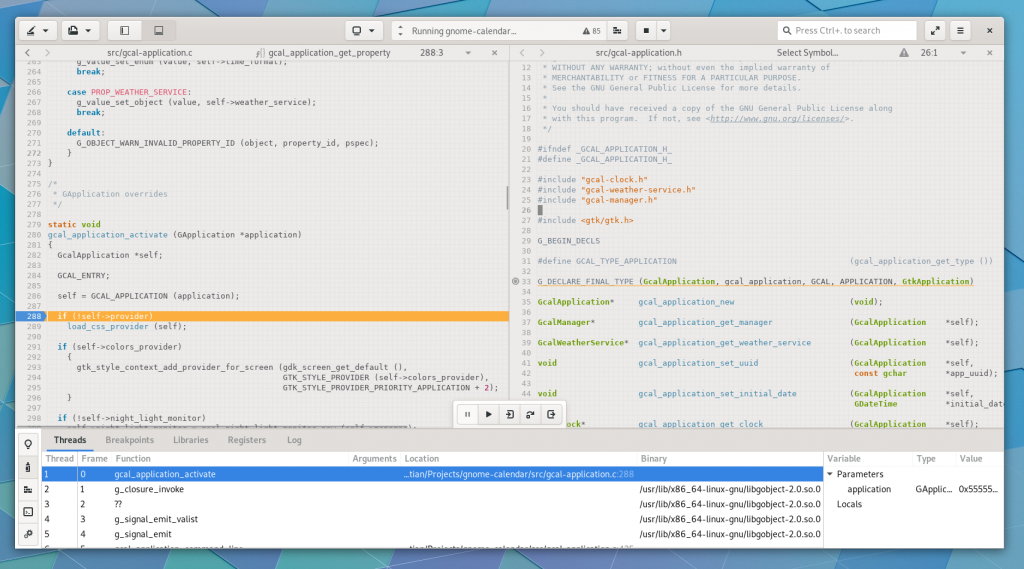

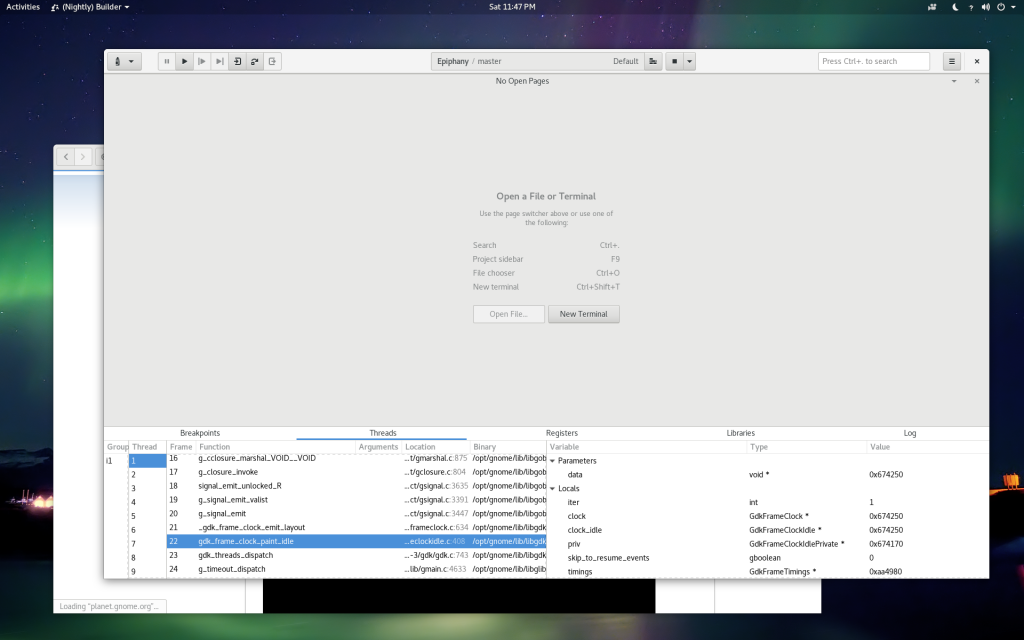

The debugger has gone through a number of improvements for resilience with modern gdb.

When Builder is full-screen, the header bar slides in more reliably now thanks to a fix I merged in gtk-3-24.

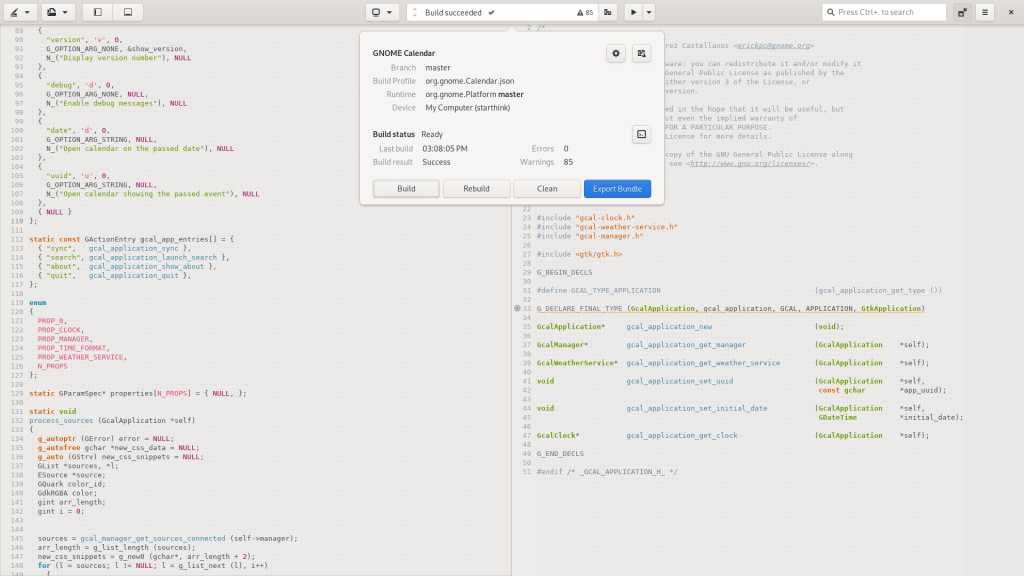

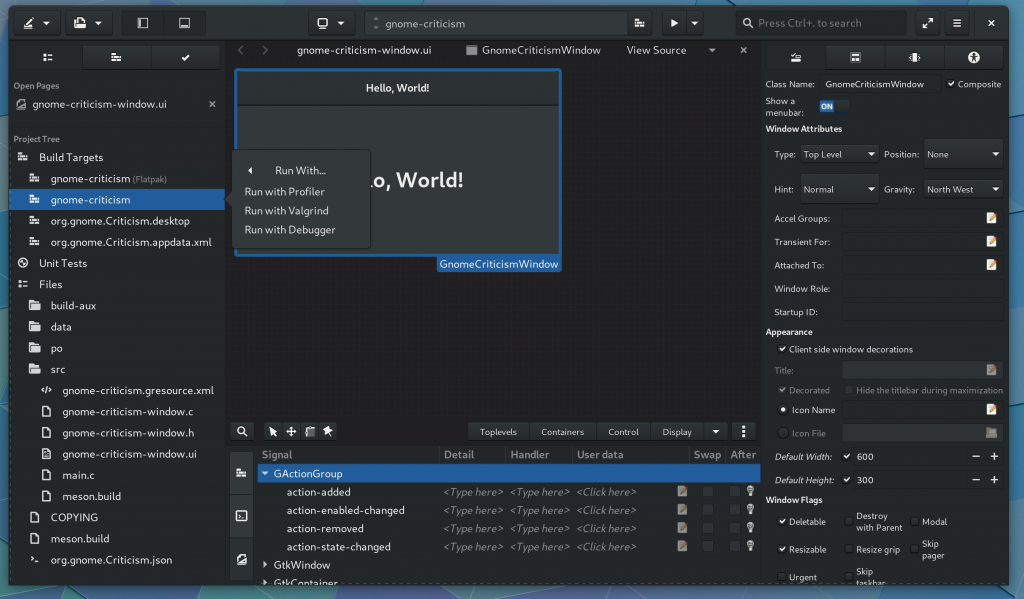

As previewed earlier in the cycle, we have rudimentary glade integration.

Also displayed here, you can select a Build Target from the project tree and run it using a registered IdeRunHandler.

Files with diagnostics registered can have that information displayed in the project tree.

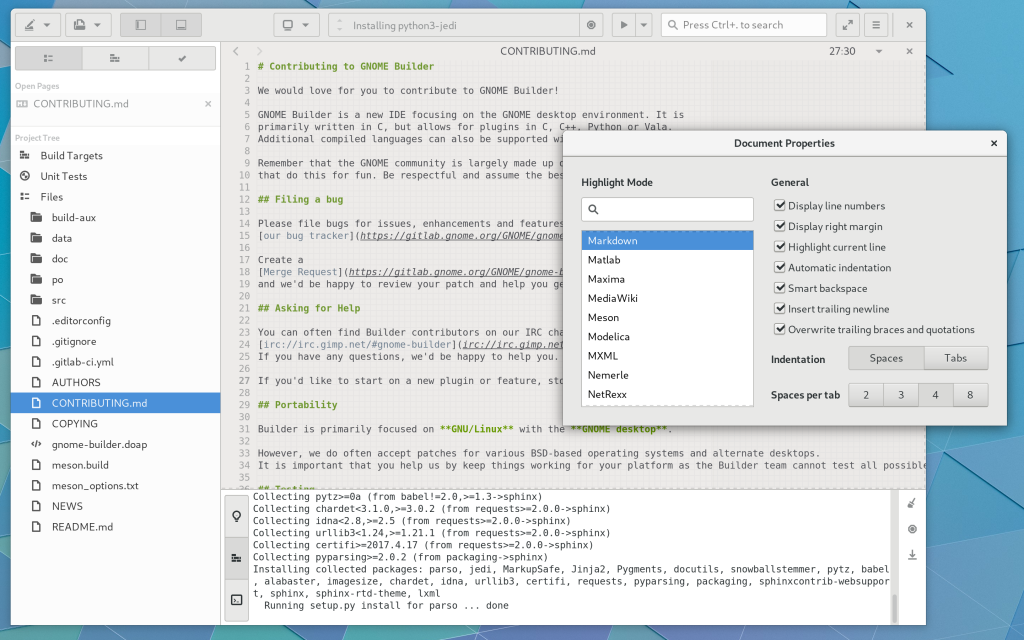

The document preferences have been simplified and extracted from the side panel.

The terminal now can highlight filename:line:column patterns and allow you to ctrl+click to open just like URLs.

In a future post, we’ll cover some of what went into the refactoring. I’d like to discuss how the source tree is organized into a series of static libraries and how internal plugins are used to bridge subsystems to avoid layering violations. We also have a number of simplified interfaces for plugin authors and are beginning to have a story around ABI promises to allow for external plugins.

If you just can’t wait, you can play around with it now (and report bugs).

flatpak install https://gitlab.gnome.org/GNOME/gnome-apps-nightly/raw/master/gnome-builder.flatpakref

Until next time, Happy Hacking!