It’s conference season and I attended the International Conference on Availability, Reliability, and Security (ARES) in Canterbury, UK. (note that in the future, the link might change to something more sustainable)

A representative of the Kent University opened the event. It is the UK’s European University, he said, with 20000 students, many of them being from other countries. He attributed that to the proximity to mainland Europe. Indeed it’s only an hour away (if you don’t have to go back to London to catch a direct Eurostar rather than one that stops in, say, Ashford). The conference was fairly international, too, with 230 participants from 33 countries. As an academic conference, they care about the “acceptance rate” which, in this case, was at 20.75%. Of course, he could have mentioned any number, because it’s impossible to verify.

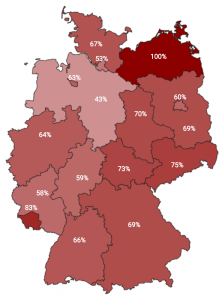

The opening keynote was given by Alistair MacWilson from Bletchley Park. Yeah, the same Bletchley Park which Alan Turing worked at. He talked about the importance of academia in closing the cybersecurity talent gap. He said that the deficit of people knowing anything about cybersecurity skills is 3.3M with 380k alone in Europe, but APAC being desperately short of 2.1M professionals. All that is good news for us youngsters in the business, but not so good, he said, if you rely on the security of your IT infrastructure… It’s not getting any better, he said, considering that the number of connected devices and the complexity of our infrastructure is rising. You might think, he said, that highly technical skills are required to perform cybersecurity tasks. But he mentioned that 88% of the security problems that the global 5000 companies have stem from human factors. Inadequate and unfocussed training paired with insufficient resources contribute to that problem, he said. So if you don’t get continuous training then you will fall behind with your skill-set.

There were many remarkable talks and the papers can be found online; albeit behind a paywall. But I expect SciHub to have copies and authors to be willing to share their work if you ask. Anyway, one talk I remember was about delivering Value Added Services to electric vehicle charging. They said that it is currently not very attractive for commercial operators to provide charging stations, because the margin is low. Hence, additional monetisation in form of Value Added Services (VAS) could be added. They were thinking of updating the software of the vehicle while it is charging. I am not convinced that updating the car’s firmware makes a good VAS but I’m not an economist and what do I know about the world of electric vehicles. Anyway, their proposal to add VAS to the communication protocol might be justified, but their scenario of delivering software updates over that channel seems like a lost opportunity to me. Software updates are currently the most successful approach to protecting users, so it seems warranted to have an update protocol rather than a VAS protocol for electric vehicles.

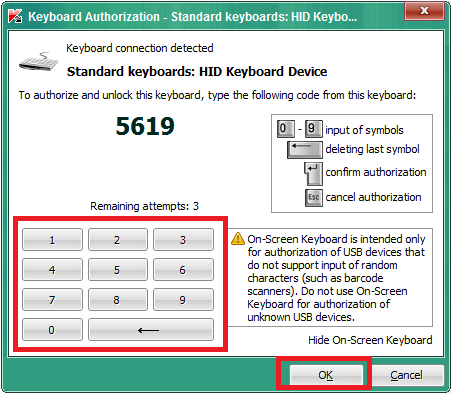

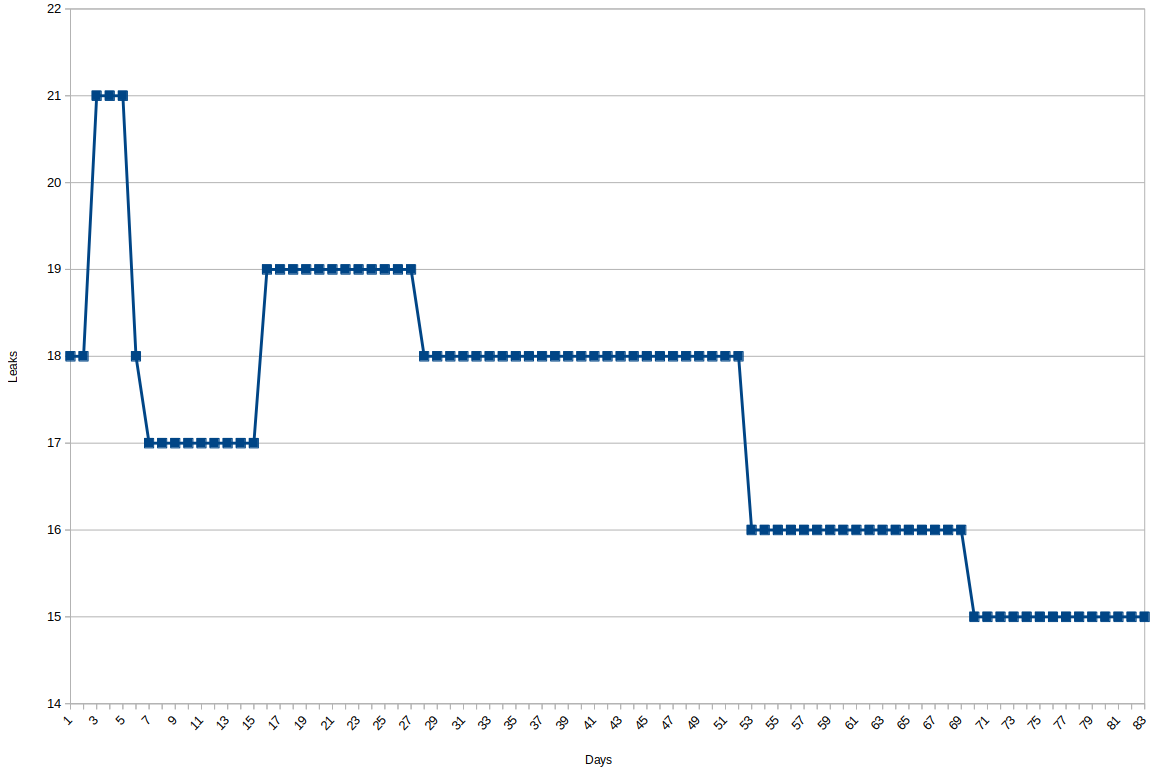

My own talk was about using the context and provenance of USB-borne events (illegal public copy) to mitigate attacks via that channel. So general idea, known to readers of my blog, is to take the state of the session into account when dealing with events stemming from USB devices. More precisely, when your session is locked, don’t automatically load drivers for a new USB device. Your session is locked, after all. You’re not using your machine and cannot insert a new device. Hence, the likelihood of someone else maliciously inserting a device is higher than when your session is unlocked. Of course, that’s only a heuristic and some will argue that they frequently plug devices into their machine when it’s locked. Fair enough. I argue that we need to be sensitive and change as little as possible to the user’s way of working with the machine to get high acceptance rates. Hence, we need to be careful when devices like keyboards are inserted. Another scenario is the new network card that has been attached via USB. It should be more suspicious to accept that nameserver that came from the new network card’s DHCP server when the system has a perfectly working network configuration (and the DHCP response did not contain a default gateway). Turns out, that those attacks are mounted right now in real-life and we have yet to find defences that we can deploy on a large scale.

It’s been a nice event, even though the sandwiches for lunch got boring after a few days 😉 I am happy to have met researchers from other areas and I hope to stay in touch.