I forgot to blog about one of my projects. I had actually already talked about it more than one year ago and we had a paper at USENIX Security.

Essentially, we built a protection against DOM-based Cross-site Scripting (DOMXSS) into Chromium. We did that by detecting whenever potentially attacker provided strings become JavaScript code. To that end, we made the HTML rendering engine (WebKit/Blink) and the JavaScript engine taint aware. That is, we identified sources of values that an attacker could control (think window.name) and marked all strings coming from those sources as tainted. Then, during parsing of JavaScript, we check whether the string to be compiled is actually tainted. If that is indeed the case, then we abort the compilation.

That description is a bit simplified. For example, not compiling code because it contains some fragments of the URL would break a substantial number of Web sites. It’s an unfortunate fact that many Web sites either eval code containing parts of the URL or do a document.write with a string containing parts of the URL. The URL, in our attacker model, can be controlled by the attacker. So we must be more clever about aborting compilation. The idea was to only allow literals in JavaScript (like true, false, numbers, or strings) to be compiled, but not “code”. So if a tainted (sub)string compiles to a string: fine. If, however, we compile a tainted string to a function call or an operation, then we abort. Let me give an example of an allowed compilation and a disallowed one.

<HTML>

<TITLE>Welcome!</TITLE>

Hi

<SCRIPT>

var pos=document.URL.indexOf("name=")+5;

document.write(document.URL.substring(pos,document.URL.length));

</SCRIPT>

<BR>

Welcome to our system

…

</HTML>

Which is from the original report on DOM-based XSS. You see that nothing bad will happen when you open http://www.vulnerable.site/welcome.html?name=Joe. However, opening http://www.vulnerable.site/welcome.html?name=alert(document.cookie) will lead to attacker provided code being executed in the victim’s context. Even worse, when opening with a hash (#) instead of a question mark (?) then the server will not even see the payload, because Web browsers do not transmit it as part of their request.

“Why does that happen?”, you may ask. We see that the document.write call got fed a string derived from the URL. The URL is assumed to be provided by the attacker. The string is then used to create new DOM elements. In the good case, it’s only a simple text node, representing text to be rendered. That’s a perfectly legit use case and we must, unfortunately, allow that sort of usage. I say unfortunate, because using these APIs is inherently insecure. The alternative is to use createElement and friends to properly inject DOM nodes. But that requires comparatively much more effort than using the document.write. Coming back to the security problem: In the bad case, a script element is created with attacker provided contents. That is very bad, because now the attacker controls your browser. So we must prevent the attacker provided code from execution.

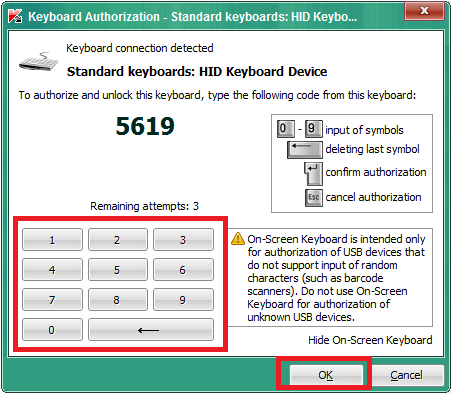

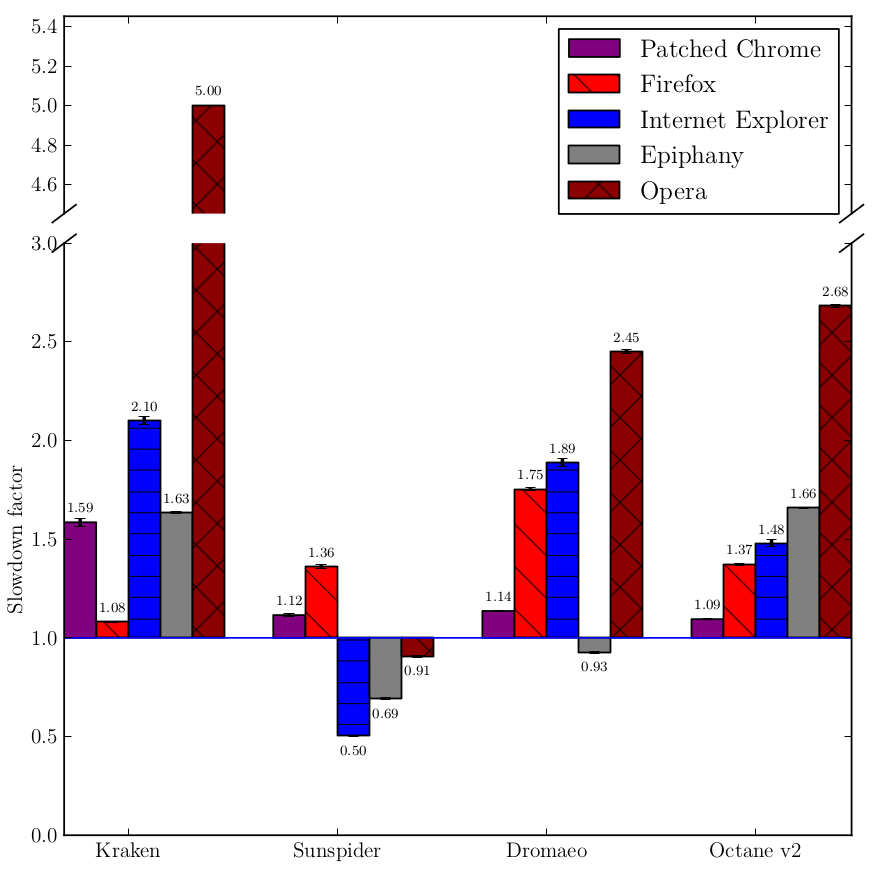

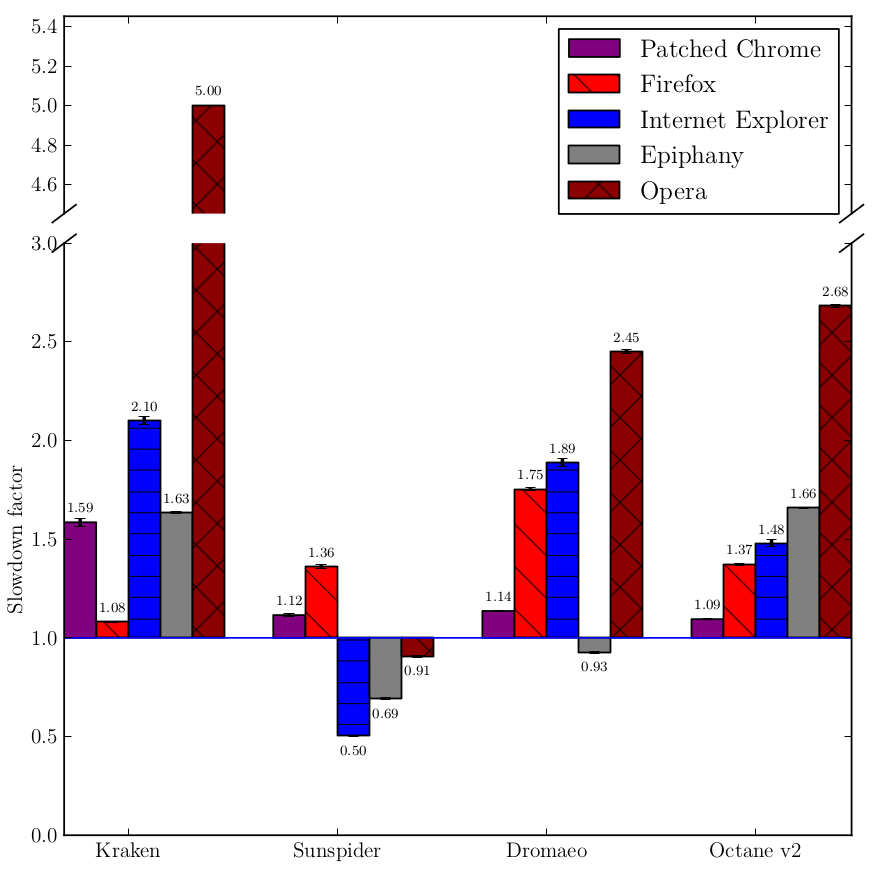

You see, tracking the taint information is a non-trivial effort and must be done beyond newly created DOM nodes and multiple passes of JavaScript (think eval(eval(eval(tainted_string)))). We must also track the taint information not on the full string, but on each character in order to not break existing Web applications. For example, if you first concatenate with a tainted string and then remove all tainted characters, the string should not be marked as tainted. This non-trivial effort manifests itself in the over 15000 Lines of Code we patched Chromium with to provide protection against DOM-based XSS. These patches, as indicated, create, track, propagate, and evaluate taint information. Also, the compilation of JavaScript has been modified to adhere to the policy that tainted strings must only compile to literals. Other policies are certainly possible and might actually increase protection (or increase compatibility without sacrificing security). So not only WebKit (Blink) needed to be patched, but also V8, the JavaScript engine. These patches add to the logic and must be execute in order to protect the user. Thus, they take time on the CPU and add to the memory consumption. Especially the way the taint information is stored could blow up the memory required to store a string by 100%. We found, however, that the overhead incurred was not as big as other solutions proposed by academia. Actually, we measure that we are still faster than, say, Firefox or Opera. We measured the execution speed of various browsers under various benchmarks. We concluded that our patched version added 23% runtime overhead compared to the unpatched version.

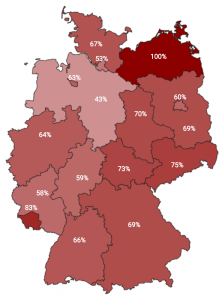

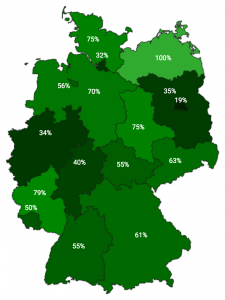

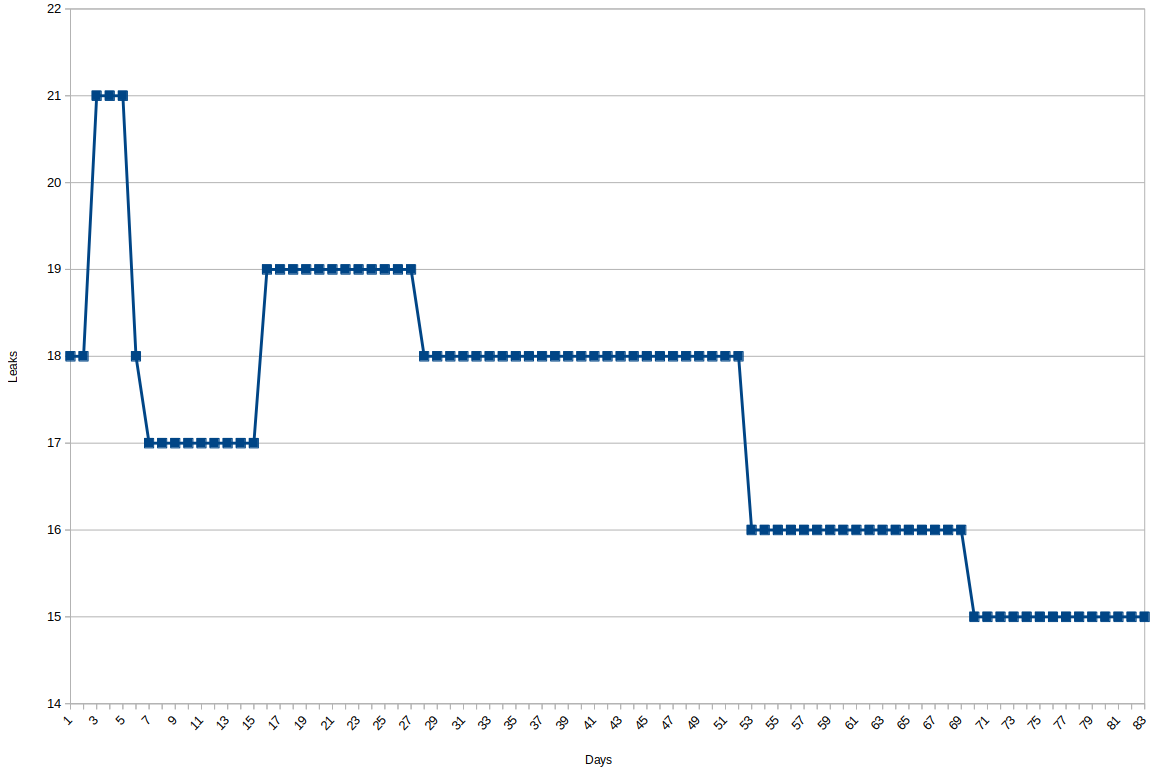

As for compatibility, we crawled the Alexa Top 10000 and observed how often our protection mechanism has stopped execution. Every blocked script would count towards the incompatibility, because we assume that our browser was not under attack when crawling. That methodology is certainly not perfect, because only shallowly crawling front pages does not actually indicate how broken the actual Web app is. To compensate, we used the WebKit rendering tests, hoping that they cover most of the important functionality. Our results indicate that scripts from 26 of the 10000 domains were blocked. Out of those, 18 were actually vulnerable against DOM-based XSS, so blocking their execution happened because a code fragment like the following is actually indistinguishable from a real attack. Unfortunately, those scripts are quite common 🙁 It’s being used mostly by ad distribution networks and is really dangerous. So using an AdBlocker is certainly an increase in security.

var location_parts = window.location.hash.substring(1).split(’|’);

var rand = location_parts[0];

var scriptsrc = decodeURIComponent(location_parts[1]);

document.write("<scr"+"ipt src=’" + scriptsrc + "’></scr"+"ipt>");

Modifying the WebKit for the Web parts and V8 for the JavaScript parts to be taint aware was certainly a challenge. I have neither seriously programmed C++ before nor looked much into compilers. So modifying Chromium, the big beast, was not an easy task for me. Besides those handicaps, there were technical challenges, too, which I didn’t think of when I started to work on a solution. For example, hash tables (or hash sets) with tainted strings as keys behave differently from untainted strings. At least they should. Except when they should not! They should not behave differently when it’s about querying for DOM elements. If you create a DOM element from a tainted string, you should be able to find it back with an untainted string. But when it comes to looking up a string in a cache, we certainly want to have the taint information preserved. I hence needed to inspect each and every hash table for their usage of tainted or untainted strings. I haven’t found them all as WebKit’s (extensive) Layout tests still showed some minor rendering differences. But it seems to work well enough.

As for the protection capabilities of our approach, we measured 100% protection against DOM-based XSS. That sounds impressive, right? Our measurements were two-fold. We used the already mentioned Layout Tests to include some more DOM-XSS test cases as well as real-life vulnerabilities. To find those, we used the reports the patched Chromium generated when crawling the Web as mentioned above to scan for compatibility problems, to automatically craft exploits. We then verified that the exploits do indeed work. With 757 of the top 10000 domains the number of exploitable domains was quite high. But that might not add more protection as the already existing built in mechanism, the XSS Auditor, might protect against those attacks already. So we ran the stock browser against the exploits and checked how many of those were successful. The XSS Auditor protected about 28% of the exploitable domains. Our taint tracking based solution, as already mentioned, protected against 100%. That number is not very surprising, because we used the very same codebase to find vulnerabilities. But we couldn’t do any better, because there is no source of DOM-based XSS vulnerabilities…

You could, however, trick the mechanism by using indirect flows. An example of such an indirect data flow is the following piece of code:

// Explicit flow: Taint propagates

var value1 = tainted_value === "shibboleth" ? tainted_value : "";

// Implicit flow: Taint does not propagate

var value2 = tainted_value === "shibboleth" ? "shibboleth" : "";

If you had such code, then we cannot protect against exploitation. At least not easily.

For future work in the Web context, the approach presented here can be made compatible with server-side taint tracking to persist taint information beyond the lifetime of a Web page. A server-side Web application could transmit taint information for the strings it sends so that the client could mark those strings as tainted. Following that idea it should be possible to defeat other types of XSS. Other areas of work are the representation of information about the data flows in order to help developers to secure their applications. We already receive a report in the form of structured information about the blocked code generation. If that information was enriched and presented in an appealing way, application developers could use that to understand why their application is vulnerable and when it is secure. In a similar vein, witness inputs need to be generated for a malicious data flow in order to assert that code is vulnerable. If these witness inputs were generated live while browsing a Web site, a developer could more easily assess the severity and address the issues arising from DOM-based XSS.